How a Small Church in Iowa Became a Catholic Worker Destination

Inside: Read about the origin of the Midwest CW Sugar Creek Gathering, take our reader survey, and more.

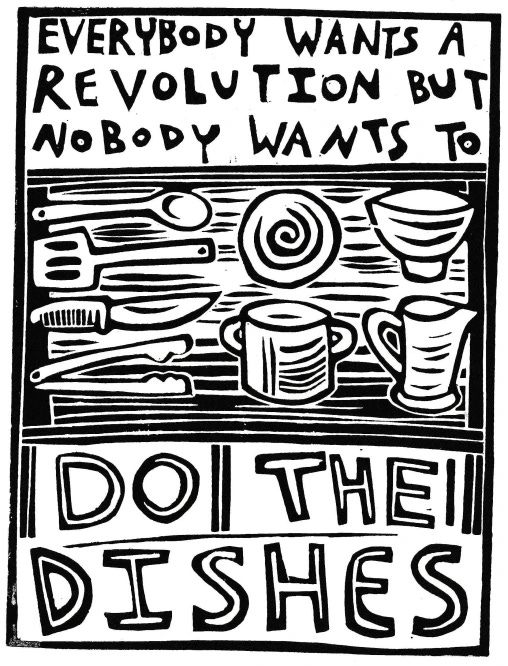

On Avalanches & Upside-Down Revolutions

As we noted last week, this issue is going to be smaller than usual because our little crew has been busy: Renée has been wrapping up the Peter Maurin Conference in Chicago, Monica is helping a family member settle into a new home, and I have been surfing an avalanche of responsibilities in a way that I couldn’t defer—sadly, my family and work obligations scuttled my plans to attend the annual Sugar Creek Midwest Catholic Worker Gathering this weekend, which is quite disappointing.

On the bright side, Renee has written up a brief history of the Sugar Creek gathering, and we continue our conversation with Mark Colville of the Amistad Catholic Worker (New Haven, Connecticut): he says Catholic Worker hospitality needs to pivot in the face of the widespread criminalization of homelessness. Catch all of that below.

What do you think?

But before you get to that (or after, if you prefer), please take a moment to complete our 10-question reader survey. We have welcomed many new readers in the past six months, and will probably cross the 3,000-subscriber mark by the end of the year. We’d love to know who you are and what you think of Roundtable. In return, we’ll be able to make changes based on your feedback so that you have a better reading experience week to week.

We’re getting a little board

Speaking of Roundtable milestones, we are finally getting an editorial advisory board. (Actually, we’re not calling it a “board,” a word whose institutional connotations might give some of our CW friends conniptions; but I couldn’t resist the pun.) We’ve reached out to a handful of Catholic Workers with deep CW experience. This little group will meet a few times a year to touch base on what we’ve been doing here at Roundtable and over on CatholicWorker.org.

The basic idea is to keep both the website and this newsletter rooted in the Catholic Worker tradition and accountable to the wider Catholic Worker community. We also expect this group to be helpful in sorting out the occasional thorny editorial question.

What we’re about, and why

Our mission is to report on the activities of the Catholic Worker Movement across its many communities. We do this because we believe that these communities put to the test, day after day, the radical proposal of the Gospel as recapitulated by Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day. That proposal, that vision of a society in which it is easier for people to be good, is so upside down and inside out that many people, including many church-going Christians, can’t quite believe that it could ever be realized. And yet, time and time again, you walk into one of these Catholic Worker communities and find, to your utter amazement, a glimpse of that Beloved Community. Time and time again, you find individuals who make significant personal sacrifices in order that others might be a little better off.

Like Mary Magdelene running home from the tomb on Easter morning, you come away from these encounters happily astonished: the Good News is no longer just an exhortation, but a reality that changes everything.

The stories of these Catholic Worker communities ought to be brought to light. It is our hope that in doing so, we are helping, in a small way, to enlarge the society they strive to bring about.

Having said all that, the movement embraces a wide range of opinions and practices among its members. For all the glimpses of Easter morning, there is also plenty of garden-variety “people being human,” and the disagreements and divisions that come with that. Navigating all that in a way that is fair and inclusive while remaining grounded in the movement’s fundamental principles can be tricky. And that’s a long-winded, roundabout way of explaining why we’re pulling together an editorial advisory board group.

Thanks, as always, for reading—and for all that you do to make the world a little easier and a little brighter.

—Jerry

FEATURED

After 47 Years, Sugar Creek Gathering Still Offers Catholic Workers a Place to Play, Pray, and Ponder

This weekend, Catholic Workers gathered at the Sugar Creek Retreat Center near Prescott, Iowa. For three days, they held roundtable discussions, shared communal meals, performed skits, sang, and prayed, surrounded by corn fields and the rolling hills of eastern Iowa’s Driftless Area.

The “retreat center” mostly consists of an aging two-story brick building and a large outdoor shelter. But for most of the past 47 years, it has been home to the Midwest Catholic Worker Gathering, often referred to simply as “Sugar Creek.” Despite the name, the gathering regularly draws people from farther afield, as well as people who are not formally attached to a Catholic Worker community but who are interested in the movement.

The first Sugar Creek gathering was held in 1978 to celebrate the fifth anniversary of the Davenport Catholic Worker. The Davenport Catholic Worker was founded by Margaret Quigley in 1973. Quigley had considered joining new Catholic Worker houses in Chicago but made her way out to Davenport, Iowa, instead.

The Davenport Catholic Worker grew fast. In five years, they took over both parts of a duplex and moved into another house on the block, which they named Peter Maurin House. Several years later, they bought a farm.

In the summer of 1978, the Davenport Catholic Worker invited Catholic Workers from across the Midwest to join them at their newly purchased St. Joseph Farm in Sugar Creek.

“Come, help us celebrate at a pot luck supper, Sunday, 3, September, at our farm in Sugar Creek,” they wrote.

The community had rented an acre of land from St. Joseph Parish, paying a small rent and a portion of the utilities.

Brian Terrell (Strangers and Guests Worker in Maloy, Iowa) was at that first Sugar Creek gathering in 1978. He was visiting from New York City, where he was volunteering with the New York Catholic Worker; the next year, he would move to Iowa to join the Davenport Catholic Worker.

At the 2023 Sugar Creek gathering, he shared some of that early history.

“We had about an acre of garden here, and we could come up here and stay in this building and do our gardening and canning. We could stay the night or just come up for a day, or sometimes people from our community would come here for a week or more for a kind of retreat and quiet time. At that time, the Davenport (Catholic Worker) House was feeding at least 40 people twice a day in a standard American kitchen, which you couldn’t do that and can tomatoes at the same time,” he said.

“So, we would come here for a day or two and can all of our tomatoes or make our pickles. We had a nice kitchen, lots of space, and when the Catholic Worker at the time in the Midwest wanted to gather, it seemed like a natural place to be. The very first years of it, there were a lot fewer of us, and there were no kids.”

For much of the Catholic Worker’s history, young people would join for a year or two before moving on—much like today’s “gap year,” he said. But then people started staying in the movement, raising families in their communities—and bringing those kids along to Sugar Creek.

Another thing that has changed is the attitude toward Catholic Worker farms, he said. “At that time, a lot of Catholic Workers thought we were being self-indulgent by gardening: ‘Food comes from Dumpsters!’ Well, now we know it comes from gardens.”

Eric Anglada of the St. Isidore Catholic Worker has helped coordinate the gathering in recent years.

The gathering, typically held on the second or third weekend of September, is “somewhat informal, somewhat planned," he said. Participants engage in introductions, fellowship, roundtable discussions, prayer, communal meals, and even lighthearted entertainment in the form of skits and songs. The gathering usually draws "old timers" who attend almost every year as well as first-time attendees.

"It's just a great mix of all generations," Anglada said. "We had someone here who was 92 years old."

While there is a large house with a bunk room and a few private rooms for elders and families with young children, most attendees opt to camp in tents. The gathering's approach to meals epitomizes the movement's ethos of hospitality and sharing. Communities and individuals bring what they can, often excess produce from their gardens or farms. "We're bringing produce, we're bringing milk, we're bringing meat," Anglada explains. "So actually, we're eating really well."

A large, covered shelter serves as the central gathering space, where most of the weekend's activities take place. The timing of the event in mid-September usually means the weather is nice: sunny days in the seventies and cool evenings, perfect for outdoor roundtable discussions.

So, even though the Davenport Catholic Worker closed in 1990, the annual tradition it started has become a beloved institution in the movement.

Hope for Amistad’s Backyard Village—and a Call for the CW to “Go to the Margins”

While the mayor of New Haven, Connecticut, continues to be “intransigent” toward the tiny house village hosted in the backyard of the Amistad Catholic Worker, recent visits by other elected officials have given Mark Colville hope that the project will be able to stay open through the winter.

“About half of the Board of Alders have already been here to tour the place,” Colville told Roundtable in a recent interview. “They’re setting up a public meeting to discuss the possibility of replicating this project on a piece of public land.”

Even more encouraging is the interest shown at the state level. “About a dozen of the state legislators have been here as well, including the president of the state legislature,” Colville said. He went on to explain that legislation is currently being considered that would authorize religious communities to use their property for emergency hospitality.

“The president of the state legislature told me that he was confident that this is going to pass in the next session,” Colville said. If passed, this legislation could effectively bypass local zoning restrictions and legalize projects like the Amistad Catholic Worker's tiny house village. Other religious organizations might be inspired to follow the community’s example.

“I’m pretty positive in terms of this coming winter that we should be able to get this thing resolved by then,” Colville said, though he admitted he might be "a little overboard on the optimism.”

The Amistad Catholic Worker began hosting unhoused people in its backyard in 2023 after the city cleared a tent city. At first, some of the former tent city residents camped in the backyard, with power and access to toilet facilities provided by Amistad. Later, the community erected the tiny houses. One former resident of the tent city died after the city’s eviction when the car he was sleeping in caught fire, according to Connecticut Public Radio.

“If you’re a homeless person living in a tent, the city doesn’t have to do anything. They just scoop you up and move you like a bag of clothes,” Colville said in July, shortly after the electricity cutoff. “We’re trying to set up a model for what a supported encampment would look like if the city took the responsibility to provide a basic infrastructure.”

Besides erecting the backyard village, Colville and members of the Amistad Catholic Worker have picketed city hall weekly; Colville was even arrested for refusing to leave a homeless encampment that the city was clearing.

The community has pointed to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as the basis for its actions and has urged the city of New Haven to “comply” with the Declaration. Article 25 of the Declaration states that “everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services….”

The developments in Connecticut come at a time when communities across the U.S. are gearing up to clear homeless encampments in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Grant’s Pass ruling permitting them to do so.

Colville, who recently traveled to the West Bank as part of a peace delegation, said that the effort to displace Palestinians from their homes there reminded him a lot of attempts to criminalize homelessness in the U.S.

“I’m drawing this connection because it’s so important in terms of what we’re trying to do to counter the criminalization of homelessness,” he said. “You know, I think the only thing the only thing that’s missing in terms of putting this kind of oppression in full operation here (in the U.S.) is that we haven’t yet directed the weaponized drones toward our neighborhood.”

Colville said he has been calling for a shift in the way Catholic Workers approach the work of hospitality for the unhoused. “The critique that I’m sort of trying to raise within the Catholic Worker Movement is that our traditional way of doing hospitality, while it’s been extremely beautiful and continues to be…I can’t imagine Dorothy Day being alive right now and not calling for Catholic Workers to be directly involved in this kind of accompaniment work—nonviolently standing our ground and resisting…. People are being pushed to the margins and criminalized there, so that’s where we need to go, and we need to decriminalize those spaces and make them safe. That’s the clear invitation that I think the Gospel and Dorothy and Peter’s thoughts are calling us to.”

CALENDAR

September 21 | Platteville, Wisconsin

Little Platte Catholic Worker Farm Landwarming and Celebration

September 24 | St. Bakhita Catholic Worker, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Contemplative Prayer to End Racism

October 4-6 | St. Francis Catholic Worker, Chicago, Illinois

Catholic Worker National Gathering

October 7 | Harrisburg Catholic Worker

Feast of Our Lady of the Rosary Vigil for Peace

October 9 - April 10 | St. Bakhita Catholic Worker, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Dorothy Day: Patron Saint of Both/And

A FEW GOOD WORDS

“A Recipe for Catholic Worker Soup: Make Too Much, Invite Too Many” (excerpt)

by Michael Garvey, originally published in The Catholic Radical, by the Davenport Catholic Worker, re-printed in The Catholic Worker, March-April, 1977. Republished in Michael Garvey’s memoir, Confessions of a Catholic Worker

Far too many modem problems (our fascination with violence, our racism, our waste of resources, our fragmentation as a people) are grounded in unnecessary fears. One minor, but definitely unnecessary, fear is the fear of making too much soup. Soup that has been reheated after forty-eight hours in the refrigerator tastes much better than the soup you made this morning, and serves as an excellent theme for even better soup.

I like to think that in the soup I had at noon today there may have been a few dim atoms of the soup served on the day our house here opened. Good soup is one more way we can preserve the treasures of the past and demonstrates that tradition is never a dead thing, but always a fresh and enriching perspective on the present. Good soup has, in common with great art, and the Gospel itself, the characteristic of eternal freshness and beauty.

The phrase "too much garlic" is meaningless.

So is the phrase "too many onions."

Roundtable covers the Catholic Worker Movement. This week’s Roundtable was produced by Jerry Windley-Daoust, Renée Roden. Art by Monica Welch. Cover photo from Sugar Creek courtesy of the Marquette University Archives.

Roundtable is an independent publication not associated with the New York Catholic Worker or The Catholic Worker newspaper. Send inquiries to roundtable@catholicworker.org.

It’s just that on-the-ground reality is much more complicated than theological or philosophical concepts which too often tend to be intellectual, theoretical and simplistic.

I’m struggling with how to respond and maybe someone else has some guidance. Reality can be pretty ugly, with the line between “right” and “wrong” being quite blurred.

I agreed with the pacifist approach of the CW until the Ukraine war. It’s easy to be a pacifist when you’re thousands of miles away on a quiet farm or even a busy house not threatened by bombs, drones, missiles or armies. Should the Ukrainian people just abandon their homes and businesses and flee, not fighting back? Should they just let the Russians grab their land and encourage Putin to invade Poland, Estonia, or any other neighboring country? No one but madmen like Putin wants war and I don’t like to see millions of dollars spent on military hardware like bombs, missiles and tanks but I see little choice.