2024 Catholic Worker in Review (Part One)

The war in Gaza, the new nuclear arms race, and the criminalization of homelessness were the focus of Catholic Worker actions, even as new houses of hospitality opened and others closed.

My wife was right…again….

My wife admonished me not to make this year-in-review issue too long. I promised I wouldn’t. She looked skeptical.

My wife is always right. As I write this, Substack has posted a big red banner across the top of the composer that reads, “Post too long for email!” The Substack equivalent of klaxons and flashing red lights, as it were.

So, here’s the deal, dear readers. We’ll start with a short “Featured” section (we’re so stoked about Magdalena’s translation project!) and close with Dorothy’s reflection for the fourth week of Advent, which focuses on the theme of obedience.

In between, we’ll present a selection of stories that you may have missed from the first five months of this year. Curious about what you missed? Click the links to read more.

Next Sunday, we’ll finish our retrospective with a look at Catholic Worker highlights from June through the end of the year.

And as a reminder, there will be no additional Roundtable or CW Reads issues until January.

May you and your circle of love and concern have a blessed and peaceful Christmas!

—Jerry

THE ROUNDUP

Featured

Dorothy’s CW Columns Translated into Spanish on CatholicWorker.org. Select pieces from Dorothy Day’s columns in The Catholic Worker are now available in Spanish at CatholicWorker.org, thanks to the translation efforts of Magdalena Muñoz Pizzulic, a member of the St. Peter Claver Catholic Worker in South Bend, Indiana. Magdalena studied the Catholic Worker Movement while pursuing a master’s degree in moral theology at the University of Notre Dame. Collaborating with Casey Mullaney, also of the South Bend CW and the Dorothy Day Guild, Magdalena is prioritizing the translation of columns that may be especially significant for a Spanish-speaking audience. Seven of Dorothy’s columns have been translated so far, of which three have been posted to CatholicWorker.org as of this writing. Stay tuned for updates on this project in 2025.

Read Selections from the London Catholic Worker Newsletter. This past Thursday’s CW Reads featured selected articles from the most recent London Catholic Worker newsletter. In “Kindness in Precarious Spaces,” Br. Johannes Maertens shared scenes from a recent visit to the Dunkirk refugee camp, where he works with an organization called Art Refuge. In “Externalisation,” Thomas Frost offered a primer on the British policy of “externalizing” its borders for the purpose of enforcement—but not asylum. And in “Muggings,” Anne M. Jones wrestled with how best to respond to her experience of “soft muggings,” especially in light of St. Francis’s call to embrace poverty. Check it out in CW Reads: “Precarious Spaces.”

2024 IN REVIEW

January

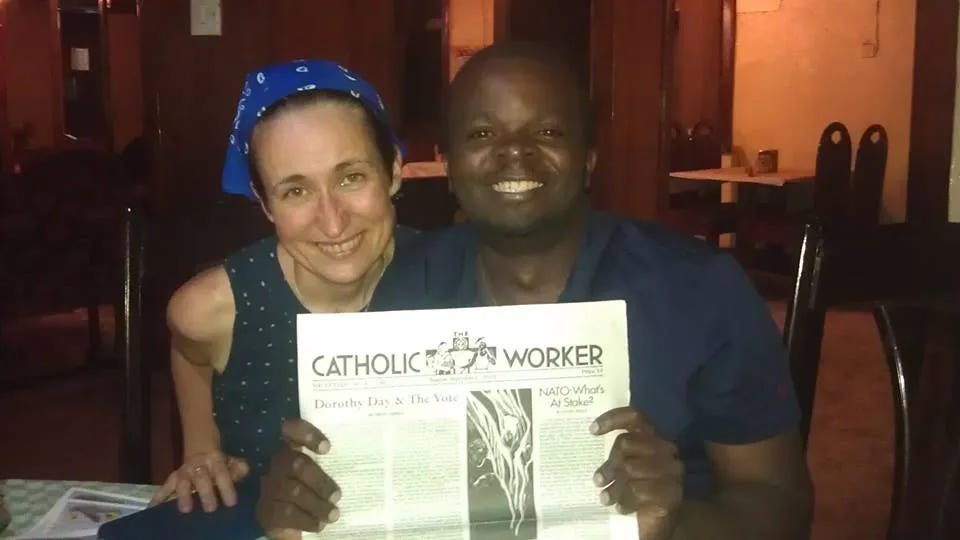

The Catholic Worker in Africa: ‘We Need It Now More Than Ever.’ This article launched our four-part series on the Catholic Worker in Africa. Since founding the Uganda Catholic Worker with two university friends in 2011, Michael Sekitoleko has experienced hunger, malaria and typhoid, evictions, skeptical Church officials, and a brutal COVID lockdown that filled his house of hospitality to capacity and killed one of his guests. He’s also been arrested by the police—not for some act of civil disobedience, but for bringing lawyers to meet with rural villagers who were about to lose their homes in an illegal land grab.

Bread and Roses CW Joins German Anti-Extremism Protests. Bread and Roses Catholic Worker (Hamburg, Germany) participated in the anti-extremism protests that took place last weekend, in which as many as 1.4 million Germans took to the streets across the country. “People for the first time understood that there is a real danger coming from the ‘right-wing,’ from the neo-fascists, the extreme nationalists,” Gerstner told Roundtable by email. “But still, many don't understand that our governments…oftentimes do the job of the right-wingers in that they do more and more anti-migration and being-hard-on-the-borders politics!”

Also:

CWers arrested in action at Pentagon marking Feast of the Holy Innocents

CW organizes "Liturgy of Repentance” in front of White House

House of Hagar suit against city of Wheeling resolved days after being filed

Taiwanese shelter for migrant workers is modeled on the Catholic Worker

February

As Detroit’s Day House Closes, Founder Finds Grace and Gratitude. Members of the Detroit Catholic Worker have announced the closure of Day House Catholic Worker as of December 2023 due to declining worker interest, community capacity, and financial resources, according to a letter by Day House community members. The community was founded in Detroit’s Corktown neighborhood in 1976 by Fr. Thomas Lumpkin and four other individuals. The diocese formally assigned Lumpkin to the Catholic Worker in 1978, making him perhaps the only priest in the world whose pastoral assignment was a Catholic Worker house rather than a parish. “It’s a vocation you need to submit yourself to, but it’s been a grace in helping me realize how much I was given,” Lumpkin told the Roundtable newsletter’s Zak Sather. “I would like to pay back a little bit by extending love and concern to people who are homeless, but I’ll never give back the extent to what I was given.”

In Kenya, a Catholic Worker by and for the Mentally Ill. Japheth Obare was twenty years old in 1995 when he had his first psychotic episode. He didn’t know it at the time, but it was the start of a long struggle with paranoid schizophrenia. He wound up in the hospital, and eventually received a diagnosis: “They said I had cerebral malaria,” Obare said, “but they do that when they don’t know, because there are no professionals to diagnose you.” That’s how he eventually formed the Catholic Friends of (the) Mentally Ill, or CFOMI, with ten other people also experiencing mild to severe mental illness. Originally founded in 2016, the group decided to affiliate with the Catholic Worker Movement in 2021, becoming only the second Catholic Worker community in Africa–and the only Catholic Worker community anywhere run by and for people with mental illness and their allies.

Also:

March

Celebrating Catholic Worker Art. While visiting the New York Catholic Worker’s Maryhouse last year, Sarah Fuller and Becky McIntyre spent a week in a storage room surrounded by 943 thin metal plates containing copies of art from The Catholic Worker newspaper. They were there to photograph, identify, and catalog each of the artworks, many of them by “the big three” Catholic Worker artists: Ade Bethune, Fritz Eichenberg, and Rita Corbin. Other art was by lesser-known artists who would have been familiar to long-time readers of the paper: Gary Donatelli and Meinrad Craighead, among others. As they worked, Fuller and McIntyre talked about an idea they had been kicking around for a while: Why not start a newsletter devoted specifically to Catholic Worker artists?

Biogas, Solar, and Creativity Fuel Sustainable Living on Peter Maurin Farm. Most Catholic Worker communities are pretty attentive to their impact on the environment, but Australia’s Peter Maurin Farm has taken environmental stewardship to an entirely new level, using just 1/20th of the energy of the average Australian through a combination of creative technological adaptations—and a willingness to live more simply. Jim and Anne Dowling have lived on the farm with their seven children and a series of guests and community members since 2000. From the beginning, they looked for innovative ways to cut down on energy use and reduce their environmental impact. Rejecting most modern, high-consumption electric appliances is the foundation of their lifestyle: no toasters, air conditioning, or hair dryers. “We also don’t have a TV ever, absolutely not,” Teresa Dowling, one of Anne and Jim’s children, says. “If you want to be entertained, read a book, play board games, that kind of thing.”

Also:

Iowa City CW Circulates Petition Against Proposed Legislation

CWer’s Palestinian Friends Report Widespread Violence, Dislocation in West Bank

Catholic Workers Join Nationwide Day of Action at Elected Officials’ Offices

April

At the Factory for World War III, Protesters Call for a Change of Heart. As most residents of Kansas City slept during the pre-dawn hours Monday, dozens of Catholic Workers rose from their beds at Cherith Brook Catholic Worker and Jerusalem Farm. After a hurried breakfast and a few strong cups of coffee, they drove half an hour to the sprawling Kansas City National Security Campus (KCNSC). As the overcast sky began to lighten, the Catholic Workers met up with local peace activists. Including the children, they constituted maybe fifty people—not much, compared to the 7,000 workers and billions of dollars powering the KCNSC. Even so, their plan was to beg those workers—and the U.S. government—to stop assembling the parts necessary to have a global nuclear war. In essence, their objective was nothing less than averting World War III.

‘Love Is the Only Thing That Multiplies When It Is Shared’: House of Grace, Kay Lasante Remember Bishop Gumbleton. As we briefly reported in our last issue, House of Grace Catholic Worker (Philadelphia) had a special connection with Bishop Thomas Gumbleton, who passed away earlier this month. Bishop Gumbleton worked with House of Grace and a local parish in Haiti to found the Kay Lasante Clinic there. In a heartfelt note to community members, his friends at both House of Grace and Kay Lasante Clinic remembered him fondly.

Also:

CWs Participate in Gaza Flotilla, Action at Senate Cafeteria

Breaking Through Fear with Love: Remembering the HIV/AIDS Ministry at Oakland’s Bethany House

LACW Files Brief as Supreme Court Poised to Uphold Bans on Sleeping in Public

May

Square Dancing and Singing as Little Acts of Resistance. Growing sweet potatoes, making cheese, weaving your own clothes, and yes, even holding a square dance or a community sing—all of these acts of production “are also a little bit of a resistance against mainstream culture,” says Mary Kay McDermott (St. Isidore Catholic Worker Farm, Cuba City, Wisconsin). “We don’t have to consume all of the things that we need in life; we can also produce them.”

‘We Are Being Arrested for Following Catholic Social Teaching.’ “It is following Gustavo Gutiérrez, Dorothy Day, Daniel Berrigan—that’s why we are being arrested, because we are following Catholic Social Teaching!” Those were the words of one of seventeen students who were arrested Thursday night on the campus of the University of Notre Dame following a peaceful protest and a hastily arranged, rain-soaked meeting with two members of the administration. The student, whose arrest was captured on video, is a Ph.D. English student. At least one of the Notre Dame students who was arrested has Catholic Worker connections. The student requested anonymity on the advice of legal counsel; all seventeen students are facing trespassing charges with a maximum penalty of a year in jail.

For Christ Room Hosts, Guests Can Become Like Family. What would it be like if even a fraction of Christian households adopted the practice of opening up a room to someone in need? Generally, people object to the idea on practical grounds. And it’s true that there are risks and sacrifices involved, which is why Peter always used to emphasize that such doing the works of mercy must come at a personal sacrifice. And yet, some people have taken the leap and found the experience to be deeply enriching and rewarding, if not always without its stresses and problems. Their stories provide a glimpse of what it might look like to realize Peter and Dorothy’s original vision in which hospitality was a habit of every Christian community.

Also:

New York Catholic Worker Vigils Outside of St. Patrick’s Cathedral

Brian Terrell Recounts “Chalk of Mass Destruction” Incident on Nevada Desert Experience Peace Walk

Los Angeles Catholic Worker Awarded Berrigan – McAlister Award

St. Francis Catholic Worker House in Columbia, Missouri to Close

WORDS FROM THE ELDERS

Reflections During Advent, Week Four: Obedience

by Dorothy Day in Ave Maria magazine, December 17, 1966

FREEDOM and authority. When I became a Catholic it never occurred to me to question how much freedom I had or how much authority the Church had to limit that freedom. I had been a Bible reader from early childhood and had accepted it as an inspired book. There was so much I did not understand in the universe that I was quite ready to accept the riddles the Scriptures imposed on me. “I would think about that tomorrow,” in the words of Scarlett O’Hara. I had quite enough already to think about today. We were supposed to obey the Commandments, and the Sermon on the Mount brought them up to a new level.

I had reached the point where I wanted to obey. I was like the child in the New Yorkerc artoon (I was nearly 30 years old) who said, “Do I have to do what I want to do today?” I was tired of following the devices and desires of my own heart, of doing what I wanted to do, what my desires told me I wanted to do, which always seemed to lead me astray. I felt always on the verge of falling into one of the seven deadly sins. Not having a parochial education, I just asked one of the Catholic Worker staff what were the seven deadly sins, and she repeated quickly, “Pride, Covetousness, Lust, Anger, Gluttony, Envy and Sloth. Much easier to remember somehow than the twelve fruits of the Holy Spirit or the fourteen works of mercy.”

I did not have the conviction, as Bishop Fletcher of Boston has, that the Ten Commandments could be amended as situation ethics demands. “Thou shalt not covet–ordinarily. Thou shalt not kill–ordinarily. Thou shalt not commit adultery–ordinarily” (as reported in the New York Post, November 12).

If they were going to be amended at all, far better that they should be fulfilled as Jesus Christ fulfilled them. “Anyone who looks to lust after a woman has already committed adultery with her in his heart.” This sounded reasonable to me even before I was introduced to St. Francis de Sales’ most understandable phrase, “taking delectation in temptation.” There were the same debates about sex and purity in the 20s, and the same scorn for what was termed then the demi-vierge, the one who played around but did not go the whole way.

Of course if God is rejected, then everything is permitted, as Ivan Karamazov reasoned. But I do not think that young people want to throw God out of the picture. Polls taken among them show that many are rejecting the Church but not God whom they find in each other–to use that beautiful phrase of the Quakers, “that which is of God in every man.” Gandhi himself said that he found God in his fellow man, and Jesus Christ said that what we did for the least of His brothers we did for Him. He also said that where two or three are gathered together in His name, there He is in the midst of them. The discovery of these things has meant a light so bright to many young people that it has blinded them to the path which leads still further, to the incomparable riches which are in the teachings of the Church, its traditions, its saints and mystics.

But this article is supposed to be about obedience. Obedient to my conscience, I became a Catholic, was conditionally baptized and said, “I do believe,” to the great and solemn and beautiful truths proposed to me.

Then for the next five years no great problems came up of obedience. The Church held up a tremendous ideal for the follower of Christ, and no matter how many times one failed, fell flat on one’s face, one might say, the Church, Holy Mother Church, was there with her sacraments of Penance and Holy Eucharist to reassure and forgive and sustain and nourish one.

In 1933 I met Peter Maurin, a French peasant who proposed to me the idea of starting a paper which had the purpose of bringing the social teachings of the Church to the man on the street.

I had been writing articles for America, the Jesuit weekly, for the Sign, the Passionist monthly, and I had been going for spiritual direction to Father Joseph McSorley, formerly superior of the Paulist congregation in New York. I asked each one of these men for advice as to whether it was necessary to ask permission before starting a venture of this kind and both editors, Father Wilfrid Parsons and Father Harold Purcell, as well as Father McSorley, told me in no uncertain terms, “No, it was not necessary to ask for permission. The thing to do was to go ahead, on one’s own, and the proof of the pudding would be in the eating, the tree would be known by its fruit, and if the work were of God, it would continue.”

I could well understand this. If Peter and I started something on our own, we alone would be responsible for its mistakes. If it were begun with the permission of the hierarchy, then they might be held responsible. I was not thinking in terms of financial responsibility. I was thinking of the positions we would take in regard to civil rights, racial as well as social justice. Without knowing St. Augustine too well (I had read only his Confessions), his dictum “Love God and do as you will” had a familiar ring. The words breathed freedom, the freedom found even in obedience to a temporary injustice, even to such a temporary injustice as stopping us once we had begun. I have never felt so sure of myself that I did not feel the necessity of being backed up by great minds, searching the Scriptures and searching the writings of the saints for my authorities.

Later I came across this passage from St. Francis de Sales: “My agent says that it is wrong to apply to Rome for things in which it can be avoided and some cardinals have said the same: for, say they, there are things which have no need of authorization because they are lawful, which, when authorization is asked for are examined in a different way. And the Pope is very glad that custom should authorize many things which he does not wish to authorize himself on account of consequences.”

Bishop O’Hara of Kansas City was a good friend and visited us in the earliest days of our work. I remember his first visit very well. We were living on Fifteenth Street, and he sought us out there on the East Side near Avenue A, not many blocks from where the Municipal Lodging House for men used to be, so that they came to visit us daily for food and clothing. He came in to the poverty of that little store front and took the trouble before he left of going to each person who was there and giving them a blessing. Later one of the girls who had worked in textile mills, who had just come to us from the hospital after the birth of her third child out of wedlock, told us most seriously, “When I kissed his ring, it was just like a blood transfusion. It did something to me.” He kept up his friendship with us, helping us when we sent out an appeal and writing us when there were things in the paper with which he disagreed. But he said to Peter on one memorable visit, “Peter, you lead the way, and we (the bishops) will follow.”

Peter knew what he meant. He meant that it was up to the laity to be in the vanguard, to live in the midst of the battle, to live in the world which God so loved that He sent His only begotten Son to us to show us how to live and to die, to meet that last great enemy, Death. We were to explore the paths of what was possible, to find concordances with our opponents, to seek for the common good, to try to work with all men of goodwill, and to trust all men too, and to believe in that goodwill, and to forgive our own failures and those of others seventy times seventy times. We could venture where priest and prelate could not or ought not, in political and economic fields. We could make mistakes without too great harm, we could retrace our steps, start over again in this attempt to build a new society within the shell of the old, as Peter and the old radicals (those who went to the roots of things) used to say.

I speak of these incidents to show the tremendous freedom there is in the Church, a freedom most cradle Catholics do not seem to know they possess. They do know that a man is free to be a Democrat or a Republican, but they do not know that he is also free to be a philosophical anarchist by conviction. They do believe in free enterprise but they do not know that cooperative ownership and communal ownership can live side-by-side with private ownership of property. I could bolster my positions by the writings in the Dominican monthly Blackfriars,for instance; one entire issue years ago was entitled, “Who Baptized Capitalism?” And by the words of the Bishop of Mwanza in Tanzania, who said the world was not divided between East and West but between the haves and the have-nots. “Only a wealthy country,” he said, “could afford the luxury of all this private ownership.”

I remember a meeting I had with three Jewish students who were putting me on a bus in St. Louis on one of my speaking trips. They said, “The one thing the Catholic Workerhas done for us is to open up our minds to the immense freedom there is in the Church.”

OBEDIENCE is a matter of love which makes it voluntary, not compelled by fear or force. Pope John’s motto was Obedience and Peace, and yet he was the pope who flouted conventions which had hardened into laws as to what a pope could or could not do, and the Pharisees were scandalized and the people delighted.

All his life long he had done his work, which sometimes meant in silence and solitude and inactivity as in Bulgaria and Turkey. But now that he was pope and his decisions concerned the whole world, he ceased to obey men. Father Ernesto Balducci, in his book John–The Transitional Pope, calls him a man of vast and vital ideas and said that his temperament led him “to escape whenever possible from behind the velvet curtains of ecclesiastical offices into the roads and squares where living men and women move.” He had accepted the frustrations of his life and his plans because “obedience is not only a moral virtue but a specific principle of faith, and as such, has reasons that reason cannot understand.”

Pope John compared his own life during those years of frustration to the waiting of Simeon in the Temple who seemed to be “wasting the years, pouring out his life as a total loss. And his life was not lost at all. The time he spent in waiting prepared him to present Christ to the world. And now I tell you that my own poor life continues to be poured out as you know; with my usual hair shirt which is so dear to me, on my back.” This he wrote in a letter to a friend some years before his election to the papacy.

Immediately following his election as pope he went to visit the prison in Rome–“You could not come to see me, so I came to see you,” he told the prisoners. Every day of his long priestly life he had prayed at the third hour of the Office, “Let our love be set aflame by the fire of Your love and its heat in turn enkindle love in our neighbors.” God had so answered his prayer that his own love kindled a fire which is sweeping over the world and the whole Church is enkindled.

This may sound like an extravagant way of speaking when we know full well the turmoil, the controversy, the impatience in the Church today which has led so many to leave convents and monasteries and even the priesthood, that high estate. Men and women have begun to exercise their freedom and are examining their own obedience, as to whether it was a matter of fear or of habit. To examine too the kind of training they in the home and in the school.

Someone said that Pope John had opened a window and let in great blasts of fresh air. With all his emphasis on obedience, I do not think he has been understood. What the American people–and I speak only of them, not knowing the condition of the Church in other countries–now feel free to do is to criticize, speak their minds. They have always been accused of a lack of diplomacy, or at least of bad manners, and they have felt it a virtue in themselves, the virtue of honesty, truthfulness. Freedom has meant searching and questioning. What do we really believe? It is as though man were realizing for the first time what is involved in this profession of Christianity. It is as though we were going through the Creed slowly, and saying to ourselves, Do I believe this, and this, and this?

When we had retreats at the Catholic Worker farm we used to renew our baptismal vows at the close of the retreat, and I remember one fellow saying, “I want to read them over carefully to see if I wish to renew them.” He meant to be humorous, because of course he knew that the vows had been made, and this recognition brought up the question of infant Baptism. The rite had been performed, the sacrament conferred, we were really in for it! We are free to obey or disobey.

Faith is required when we speak of obedience. Faith in a God who created us, a God who is Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Faith in a God to whom we owe obedience for the very reason that we have been endowed with freedom to obey or disobey. Love, Beauty, Truth, all the attributes of God which we see reflected about us in creatures, in the very works of man himself whether it is bridges or symphonies wrought by his hands, fill our hearts with such wonder and gratitude that we cannot help but obey and worship.

The knowledge of Scripture is knowledge of Christ and His teaching. One time Jacques Maritain spoke to us in a little dingy church hall in the Italian section of New York, a hall which was dirty and cold and smelling of beer from a party the night before. (Smokey Joe, so called from the “smoke” he had consumed in his long life before he settled down at the Catholic Worker, had refused the pastor’s appeal for volunteers to paint the hall, judging the pastor guilty of contributing to the delinquency of his parishioners. Jacques Maritain, who loves the poor, spoke simply of the love of God and especially of the need to study the Scriptures in order to find Christ, Him whom our soul loves. “Read the Gospel prayerfully,” he said, “searching for the truth,not just to find something with which to back up your own arguments,” he added with humor.

I thought, as he spoke, of St. Therese who wore pressed against her heart, under her habit, the Gospel of Jesus Christ, as one would a love letter. I think too of Dostoievsky’s Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, and the little Testament given him on his way to Siberia, which brought him his knowledge of salvation through the forgiveness of his sins.

Lord, I believe, help Thou my unbelief. My faith may be the size of a mustard seed but even so, even aside from its potential, it brings with it a beginning of love, an inkling of love, so intense that human love with all its heights and depths pales in comparison.

Even seeing through a glass darkly makes one want to obey, to do all the Beloved wishes, to follow Him to Siberia, to Antarctic wastes, to the desert, to prison, to give up one’s life for one’s brothers since He said, “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brothers ye have done it unto me.”

But how much easier it is to obey the least ones, than the great ones of the earth, whether they are princes of the church or state.

It has seemed to me always that one of the proofs of that great catastrophe, the Fall, is man’s almost instinctive desire to disobey, on the human level, on the natural level. It can be observed from earliest youth.

When I was raising my own small daughter and at the same time took care of the children of two Village women one summer at the beach, one of the women used to lecture me on not interfering with the freedom of her child. “Never say ‘No’ to him,” she would tell me. “You must say, ’Wouldn’t you rather do this, or that? ’Offer him an alternative. When you say no, it just puts his back up.”

The fairy tales we read to children are full of this matter of obedience and disobedience, and the fearful consequences of disobedience–the story of Bluebeard, the story of Pandora’s box, and so on. On the other hand, obedience, blind obedience, is always rewarded. I was just reminded of the little girl who obligingly went out to pick strawberries in January, and as she swept off the steps at the command of a little dwarf, there she found the strawberries she had been bidden to pick. This reminds me of St. Teresa’s emphasis on obedience even to the unquestioning planting of a picked cucumber, or St. Ignatius’ command to plant a cabbage upside down. This example was given last month during the press discussion of the rebuke to the Jesuits by Pope Paul, who seemed to think they were straying from obedience to papal directives to which they were sworn.

Such obedience never has surprised me, convert that I am. I felt it was part of love, of loyalty, of abandonment, part indeed of that folly of the Cross so emphasized by St. Paul.

Obedience, I thought, meant an ordered universe and was proper response to authority. It meant people working together for the common good. A man had authority when he knew what he was doing, whether performing an operation, filling a tooth, directing a symphony. If a man was an authority in his field, it meant obeying his directions whether, as around the Catholic Worker, it meant Hans in the kitchen, Mike in the engineering line, John in the fields or Martin Corbin in the editor’s chair. In the House of Hospitality in the city, it meant whoever was “in charge,” who would take the responsibility of doing the job, getting the tobacco, shopping for the groceries, giving out the flop money or carfares or emergency gifts or loans, getting the speakers for Friday night meetings. Authority was certainly decentralized and many shared in it.

Philosophical anarchism, decentralism, required that we follow the Gospel precept to be obedient to every living thing: “Be subject therefore to every human creature for God’s sake.” It meant washing the feet of others, as Jesus did at the Last’ Supper. “You call me Master and Lord,” He said, “and rightly so, for that is what I am. Then if I, your Lord, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. I have set you an example; you are to do as I have done for you.” To serve others, not to seek power over them. Not to dominate, not to judge others.

Simone Weil has a great deal to say about obedience. “The idea of the despised and humiliated hero which was so common among the Greeks and is the actual theme of the Gospels,” she writes, “is almost outside our Western tradition which has remained on the Roman road of militarism, centralization, bureaucracy and totalitarianism.

“Every new development for the last three centuries has brought men closer to the state of affairs in which absolutely nothing would be recognized in the whole world as possessing a claim to obedience except the authority of the State.”

How strong and positive a virtue is this obedience to God and to one’s conscience! St. Peter said, speaking for himself and the Apostles: “We must obey God rather than men.”

Certainly the staff of editors and all the volunteers who are so at home with us that they call themselves Catholic Workers must have tried the patient endurance of the chancery office in New York, not only because of our frequent sojourns in jail and because of the controversial nature of the issues taken up in the paper and by our actions, but also because of the false ideas put forward by many of our friends as being our positions.

One time I made the statement, whether in writing or in a speech I do not remember, that I was so grateful for the freedom we had in the Church that I was quite ready to obey with cheerfulness if Cardinal Spellman ever told us to lay down our pens and stop publication. Perhaps I had no right to speak for more rebellious souls than mine. Or for those whose consciences dictated continuance in a struggle, even with the highest authority, the Church itself. Perhaps I have sounded too possessive about the Catholic Worker itself and had no right to speak for the publication, but only for myself. I do know that Peter Maurin would have agreed with me. Most cradle Catholics have gone through, or need to go through, a second conversion which binds them with a more profound, a more mature love and obedience to the Church.

I do know that my nature is such that gratitude alone, gratitude for the faith, that most splendid gift, a gift not earned by me, a gratuitous gift, is enough to bind me in holy obedience to Holy Mother Church and her commands.

I consider the loss of faith the greatest of disasters and the greatest unhappiness. How can one help grieving over friends and relatives and how insistent should be our prayers? We should be importunate as the friend trying to borrow some bread to feed his late guests, as the importunate widow before the unjust judge. But obedience to the command “Search the Scriptures” will give us the reassurance we need. Will a father, when he is asked for bread, give his son a stone?

Of course, it does not necessarily follow that one “out of the Church” has lost his faith. His rebellion may be the first step in examining his belief, and may lead to his first valid act of faith. C. S. Lewis has said something like this, but I do not know where, though it comforts me to believe it.

But for me, faith and Church, and obedience to the Church, are tied together; and my gratitude for this sureness in my heart is such that I can only say, I believe, help Thou my unbelief. I believe and I obey.

About us. Roundtable covers the Catholic Worker Movement. This week’s Roundtable was produced by Jerry Windley-Daoust and Renée Roden. Art by Monica Welch at DovetailInk. Roundtable is an independent publication not associated with the New York Catholic Worker or The Catholic Worker newspaper. Send inquiries to roundtable@catholicworker.org.

Subscription management. Add CW Reads, our long-read edition, by managing your subscription here. Need to unsubscribe? Use the link at the bottom of this email. Need to cancel your paid subscription? Find out how here. Gift subscriptions can be purchased here.

Paid subscriptions. Paid subscriptions are entirely optional; free subscribers receive all the benefits that paid subscribers receive. Paid subscriptions fund our work and cover operating expenses. If you find Substack’s prompts to upgrade to a paid subscription annoying, email roundtable@catholicworker.org and we will manually upgrade you to a comp subscription.