An Unsettling Settlement

"What does it mean that the Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles is able to survive the loss of $1.5 billion?" an essay by Matt Harper from the Los Angeles Agitator

Abel the Personalist

I came across Matt Harper’s article in the Catholic Agitator, the newspaper of the Los Angeles Catholic Worker, and it instantly reminded me of a passage in The Long Loneliness in which Dorothy Day describes her conversion.

In the chapter “Love Overflows,” Dorothy writes of her immense, unstoppable desire to be united with Christ in his Church, even at the cost of living as husband and wife with the love of her life. But, just after she describes her desire to be united with the Mystical Body of Christ so vividly, she writes of:

“The scandal of businesslike priests, of collective wealth, the lack of a sense of responsibility for the poor, the negro, the worker…even the oppression of these and the consent of the oppression of them.”

She writes that the lack of ecclesial challenge to the “industrial-capitalist order”

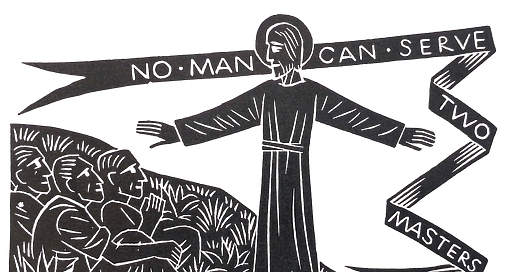

Made me feel often that priests were more like Cain than Abel. “Am I my brothers’ keeper?” they seemed to say in respect to the social order.

It is a cognitive dissonance, Dorothy notes, that the clergy who cause scandal by “centralizing and departmentalizing, involving themselves with bureaus, building, red tape, legislation, at the expense of human values,” are also the ones who dispense the sacraments. She notes that they are also “victims” of this industrial-capitalist system.

Matt Harper’s essay proposes a Church that is more like Abel: more willing to make the personal sacrifice of love to which the worship of God calls us.

peace,

Renée

An Unsettling Settlement

By Matt Harper | From the April 2025 edition of the Los Angeles Catholic Worker’s Catholic Agitator

I spent much of my early years in the pews of Saint Bede Catholic Church. I remember sitting there one Sunday while our relatively apolitical pastor stood at the lectern. He cautioned us about a new California Bill that sought to extend the statute of limitations for victim-survivors of sexual abuse to report the violence done to them. He then invited the ushers to pass out pre-written postcards and invited us to let our State representatives know how we hoped they would reject this bill.

Now, I have plenty of memories of parishioners tabling outside of Mass for assorted causes and measures. I remember announcements for service days and politically oriented community events. But I have no other memory of a St. Bede priest using precious liturgy time to get us to participate in lobbying our representatives. Everything about the activity made it clear this was clearly not a project he dreamed up himself.

I cannot remember what year this happened. It was likely before California extended the statute of limitations for civil charges to be filed in cases around sex-related child abuse in 2003, which led to the first major Archdiocese of Los Angeles settlement of $660 million in 2007 for the 508 plaintiffs who had been sexually abused by priests, staff, or laity. Or it might have been years latr, as California’s Governor prepared to sign a law that extended the statute of limitations again, which led to the recent $880 million settlement by our Archdiocese of Los Angeles for the 1,353 plaintiffs whose allegations of sexual abuse were found to be sufficiently substantiated as to warrant settlement.

Obviously, questions abound around this horrible legacy in our Church. Why did our Church (and many within it) handle the sexual violence the way they did? How were they able to? Why did Church leaders try to fight extending the statute of limitations for victims to file claims? The list is long.

But this recent settlement has invited me to reflect beyond the specifics of the violence and the institutional practices and culture that allowed this to happen. What does it mean that the Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles is able to survive the loss of $1.5 billion? What does it mean that we can still expect to employ 800+ staff, run 300+ parishes, and operate 250+ schools after having paid such costly settlements?

I think about the foundational invitation of Jesus and early Christian community to consider what we do with our excesses and find myself befuddled that we had such stores on earth as to be able to pay these settlements. We show our arrogance and lack of faith every time we refuse to practice Christ’s teachings. After suffering so many blows to our credibility, I am left to wonder: do we have another $1.5 billion in assets sitting somewhere collecting interest? Do we really have another $811 million in investments? What harm are those perpetuating to profit us?

As I read articles about Catholic dioceses transferring real estate parcels to parishes, moving wealth into external charities and dummy corporations, and reclassifying other assets in preparation for sex abuse payouts, I cannot help but wonder: did our Archdiocese work to shield ourselves, too? While naming that these settlements would have “very serious and painful consequences” for them, and that the months ahead would include “a great deal of uncertainty and hard decisions,” did we engage in acts so as to ensure victims would be limited in the resources they could access for the abuses they suffered and the trauma these have brought? And what does it say that our aim was to “provide just compensation to the survivor-victims of these past abuses while also allowing the Archdiocese to continue to carry out our ministries to the faithful and our social programs serving the poor and vulnerable in our communities”? What makes us think that being able to “weather” the costly consequences of this legacy is really what is best for us, is really what Jesus is inviting us into at this moment?

Maybe it is time to begin to demand that local communities provide direct aid—at personal cost—to those struggling in their neighborhoods rather than letting it be outsourced to others. Maybe it is time for the end of too-big-to-fail bureaucracies and our pursuit of reasonable solutions.

As Archdiocese of Los Angeles lawyers undoubtedly labored to minimize payouts, did anyone ever stop to consider that it might be valuable for us not to try and mitigate the hardships and pain this crisis will bring to us? That maybe we should go through this valley of the shadow of death in full?

Harm is not limited to large, wealthy, bureaucratic institutions, but these often create cultures and qualities of relationships that make harm more likely. Maybe this crisis is inviting us to interrogate the nature of our vulnerability, our openness to feedback and collaboration, and our commitment to accountability and healing.

After all, to paraphrase the current Aims and Means of the Catholic Worker: “Because of the sheer size of institutions, we tend towards government [and Church] by bureaucracy—that is government [and Church] by nobody.” Maybe our Church would benefit from returning to the smaller, more intimate days. Maybe we need to let the rigid structures and top-down authority crumble so that personal relationships and community discernment can take root and direct us once again. One of my former housemates grew up in a place where Christianity was illegal. His family and those who came to believe in Christ had to pass their faith in secret and share their limited resources. One of his birthdays was their first opportunity to gather for a mass. They had to wake up every day and courageously decide whether they would risk their faith again.

Maybe our Church would find an integrity by getting back to the days where people had to want their Church so badly that they had to find each other and come together, risking much to create small community churches in their homes. Maybe we have something to gain by not having such power, such abundance, such machinery that controls so much. Maybe we should give up this notion that the Diocese (or other institutions) should hold the bulk of the responsibility for social programs. Maybe top-down programs are insufficient. Maybe it is time to begin to demand that local communities provide direct aid—at personal cost—to those struggling in their neighborhoods rather than letting it be outsourced to others. Maybe it is time for the end of too-big-to-fail bureaucracies and our pursuit of reasonable solutions.

As our Church faces the many challenges that this moment provides, maybe it is time to stop our deference to old rules and antiquated traditions made without the full input of our community. Maybe it is time to see how the Spirit is inviting us in this moment to revive Christ’s radical end to divisions and expansive commitment to intimacy, vulnerability, and justice today.

“Master,” said John, “we saw someone driving our demons in Your name, and we tried to stop them, because they were not one of us.” “Do not stop them,” Jesus replied, “for whoever is not against you is for you.” I am for my Church but not the one I see is becoming. Though the Archdiocese has assured its congregations after each settlement that the financial burden for this heinous legacy would not be put on the backs of its flock but instead paid from reserves, investments, ADLA assets, loans, and insurance companies, as well as from various religious orders and others named in the litigation, where else have their resources ever come from that isn’t the people? How could the debts be being settled by anyone but us? Thus do we have a right to be part of the conversation about what comes next for our Church?

Maybe it is time that we use the collection baskets as our way to invite our Church into the movements of the Spirit today. Maybe our reimagining how our money gets used in the promotion of our faith and values will help us build the Church we need for this moment. Maybe it is time we demand our precious liturgy time be used for other endeavors, ones actually committed to justice and equity in the political and social dimensions of our society. I pray that the people harmed by our Church—both past and present—get the healing and support they deserve. I pray that I and other people of faith will be courageous enough to continue to push our communities as it is our work to help move our Church. And I pray that as our Church is given more opportunities to reckon with its past that it leaves an indelible mark on us such that we are transformed forever. We have shown the atrocities we are capable of but we have also showed the good we can do. Let us be a part of the transformation our Church and society is yearning for today. Ω

Matt Harper is a Los Angeles Catholic Worker community member and co-editor of the Agitator. This article first appeared in the April 2025 edition of the Agitator. Read the Agitator online.

About us. Roundtable is a publication of catholicworker.org that covers the Catholic Worker Movement.

Roundtable is independent of the New York Catholic Worker or The Catholic Worker newspaper. This week’s Roundtable was produced by Renée Roden and Jerry Windley-Daoust. Send inquiries to roundtable@catholicworker.org.

Subscription management. Add CW Reads, our long-read edition, by managing your subscription here. Need to unsubscribe? Use the link at the bottom of this email. Need to cancel your paid subscription? Find out how here. Gift subscriptions can be purchased here.

Paid subscriptions. Paid subscriptions are entirely optional; free subscribers receive all the benefits that paid subscribers receive. Paid subscriptions fund our work and cover operating expenses. If you would like to stop seeing Substack’s prompt to upgrade to a paid subscription, please email roundtable@catholicworker.org.

“After all, to paraphrase the current Aims and Means of the Catholic Worker: “Because of the sheer size of institutions, we tend towards government [and Church] by bureaucracy—that is government [and Church] by nobody.” Maybe our Church would benefit from returning to the smaller, more intimate days. Maybe we need to let the rigid structures and top-down authority crumble so that personal relationships and community discernment can take root and direct us once again.”

What about the Catholic school system? It seems that the Catholic schools are now serving primarily the upper classes, while the poor are left in the public schools. How about the Church using the resources that are now used in the Catholic school system for Confraternity of Christian Doctrine and other programs which are open to the poor?