Can the Catholic Worker Reinvigorate the Church?

A new book says the Catholic Worker points the way to a more joyful Christianity. Plus: The L.A. Catholic Worker on Grants Pass; CW community updates; and protesting Citigroup's climate investments.

On Humus and Humility

“To garden is a humbling experience,” members of the New York Catholic Worker write in the June/July issue of The Catholic Worker. This was in an article about their now-famous rooftop garden.

Yes! I silently agreed, thinking of my own humbling gardening experience this summer. I like to call my garden “biologically diverse,” which is to say that besides the marigolds, cosmos, tomatoes, basil, and lettuce, there are a fair number of weeds.

Also, the tomato plants have succumbed to a fungal infection—again!—leaving them looking like droopy green skeletons.

But that isn’t what the NYCW crew was going for. “To garden is a humbling experience,” they wrote, “which reminds us that we all exist as part of a grander narrative.” They went on to invoke Thoreau, Robin Wall Kimmerer, and the prophet Isaiah. They talked about “spiritual-material seeds” and “the celestial dance of galaxies” and “the wisdom of ancient trees.”

“What joy it brings as we taste even one leaf of kale or lettuce together in the kitchen,” they wrote. “It is truly an amazing journey which leads us to love more deeply.”

Darn it, I thought. Not only do those New York Catholic Workers have a better garden than me (my lettuce is bolted, my kale is kaput), they even have a fancier ecological spirituality than me.

Well, what are you going to do? Those New York Catholic Workers excel at everything.

Jerry

FEATURED

Catholic Worker Points the Way to a More Joyful Church, Author Says

People who go to church do so because they are looking for “something more” that they can’t find in their ordinary lives, says Colin Miller—something beyond screen-based relationships, unfulfilling work, and a culture that encourages self-fulfillment over community.

Unfortunately, too many churches try to feed that hunger for “more” with low-commitment gatherings, drive-by service projects, commuter fellowship, and pew sitting, Miller says. As someone who has worked in the Church, he knows what he’s talking about.

But beside his position at a Catholic parish in Saint Paul, Minnesota, he also belongs to the Maurin House Catholic Worker in the suburb of Columbia Heights. Now, in a new book, he proposes that the principles that animate the Catholic Worker Movement ought to also animate the wider Church.

Miller wandered into the Catholic Worker on his way to pray at his local parish while he was a graduate student at Duke University. The small band of homeless men who gathered around the parish property slowly introduced themselves to him, and eventually Miller and his friends formed a sort of ad hoc community with them. Excited by this new experience of Church, he and his friends hit the divinity school library, where their searches for “homeless,” “fellowship,” “poverty,” and “hospitality” eventually led them to the Catholic Worker.

Miller tells this story in the introduction to his new book, We Are Only Saved Together: Living the Revolutionary Vision of Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement, published Friday by Ave Maria Press. Here’s an excerpt from that introduction, picking up from where his discovery of the Catholic Worker leaves off:

This was by far the most compelling model for the Church’s engagement with the poor I had come across. Actually, it was the most compelling model of the Church that I had come across. I was (and am) about as white-bread as you can imagine. I grew up happily in the Minneapolis suburbs playing sports and Nintendo and had come to Durham for graduate work in theology.

I liked the Church and thought I knew a fair amount about it, but it had never even occurred to me to get to know any homeless people. But something about the situation I had stumbled into struck me as right. A church should have the poor gathered around it. The smell of pews and incense and the smell of folks who hadn’t had a shower in a few days somehow went together.

For the Catholic Worker, the Church was not some theory—it was not just a set of beliefs or moral principles. Each day when I walked up to St. Joseph Parish on this little corner of Main Street, I could see the Gospel. The simple existence of that place, with its round of prayers and mix of characters, was the closest I’d ever come to Jesus talking to me. It was beautiful. It was only later when I discovered that Day said that the world will be saved by beauty.

Part of this beauty was not only taking responsibility for the poor as Christians, but, as Day and Maurin emphasized, learning that in many ways the poor were there to help me. So the goal was not “meeting needs,” but friendship. The goal was a new kind of community, which the Church, they said, had always been meant to be. That’s what this book is about.

. . . . .

People ask me, “What can I do for the homeless?” I think it’s because they suspect there must be more to what Jesus says about the poor than writing checks to charities or volunteering. We have all heard that following the Gospel is supposed to fill us with joy, and we rightly wonder if this could take us beyond simply being nice to one another.

In one sense we are relatively happy, and we put on a pleasant face most of the time. On the other hand, many of us are vaguely aware that we are sick of our own attempts to distract ourselves through another day by constant busyness, often superficial relationships, and, yes, more screens. We are serious about our faith, but at the same time we fear that without the next beep, buzz, ring, podcast, or commitment, the boredom and despair we occasionally glimpse might jump out and swallow us.

So we come to church, yes, because we really believe, but also because we sense that the Church should have something to say about the fact that the shape of our lives is somehow not satisfying us. Churches, too, do their best to respond, and yet often struggle to break out of the mold of offering as cures simply more of the disease: low-commitment gatherings, commuter fellowship, virtual “connections,” and yes, even more screens.

We are longing for the Church to give us a vision of life that is a compelling alternative to this status quo. Many of us have a secret hope for a whole alternative way of life, with a depth that corresponds to the seriousness with which, at our best moments, we take our faith.

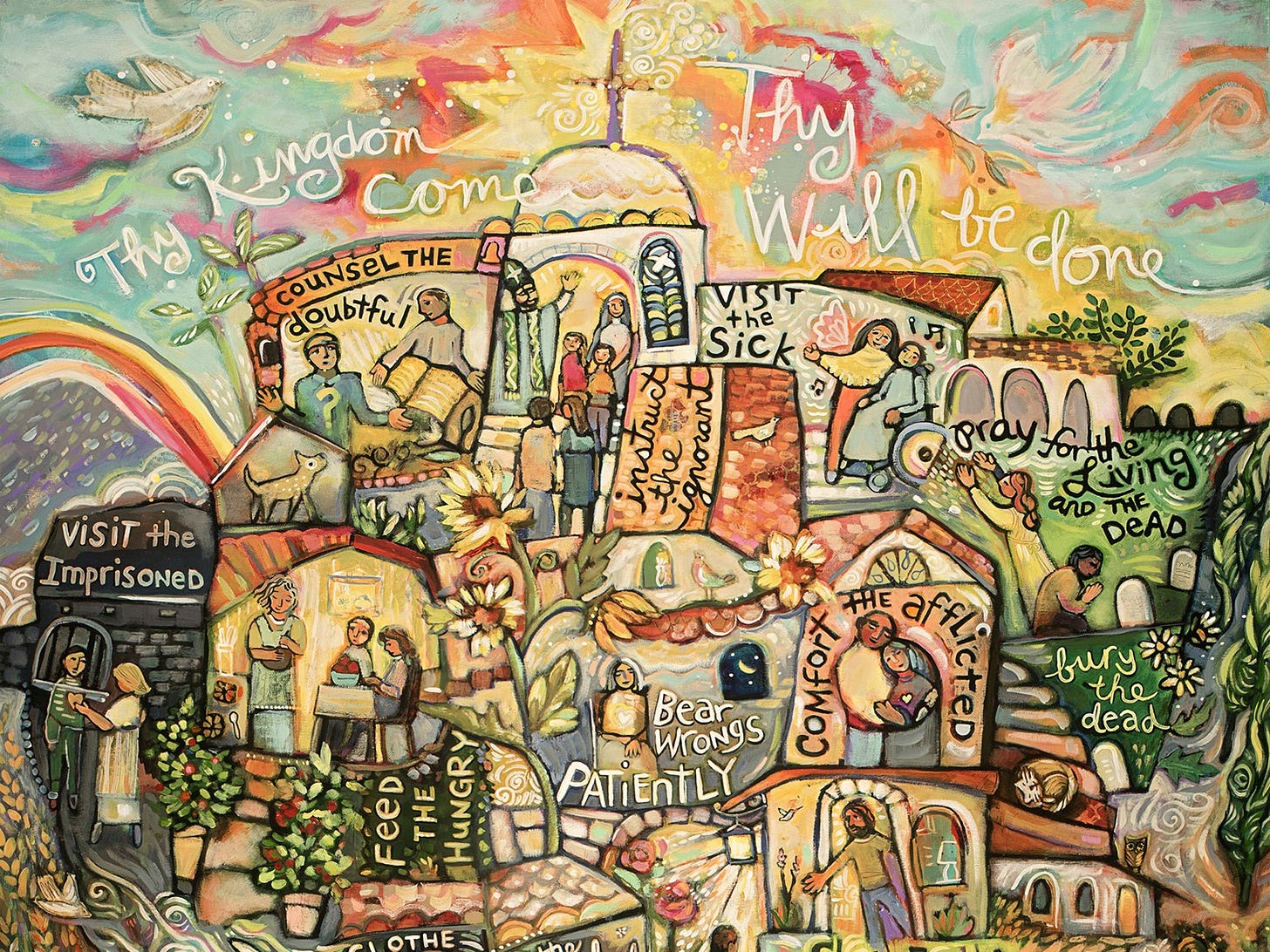

This book suggests that the Church has always had a vision for this kind of living, and the principles that animate the Catholic Worker can help us rediscover it and bring it to life wherever we are. It is a life of regular common prayer, material simplicity, fellowship with the poor, good work, and real flesh-and-blood daily relationships, rubbing shoulders with those who are doing the same. It is a life of friendship, adventure, humor, joy, and learning to take God seriously but ourselves lightly. This book outlines this vision, explains it, and says why it is so deeply relevant for those of us choosing to be in the pews today.

Miller is Director of the Center for Catholic Social Thought at the Church of the Assumption in Saint Paul; his work has often appeared in Roundtable. You can read the first part of the introduction to his new book at CatholicWorker.org; part 2 will appear in next week’s Roundtable.

Duluth’s Hildegard House Sponsors Asylum Seekers and Refugees

Joan Bromberek, a student at Loras College who is interning with Roundtable this summer, has been visiting Catholic Worker communities in the Upper Midwest. In June, she visited Hildegard House in Duluth, Minnesota, to learn more about the community’s work with refugees. Here’s an excerpt from her story:

On a sunny Thursday at the end of June, dozens of people from the Duluth area gathered at the College of St. Scholastica to celebrate World Refugee Day. Among the lead organizers of the event was Michele Naar-Obed, co-founder of Hildegard House Catholic Worker, where migrants and asylum seekers have received long-term hospitality since 2020.

“Michele gets stuff done with community,” said Andrea Gelb, emcee for the event.

It’s true: Naar-Obed and the entire Hildegard House Catholic Worker have been advocates for social justice in the Duluth area since the community was founded in 2015.

Originally, the community was founded with a focus on serving women escaping sex trafficking. But as it became apparent that the community wasn’t fully equipped to meet the needs of those women, they began looking for new ways to serve.

In 2018, Naar-Obed traveled to the Arizona-Mexico border with the Christian Peacemaker Team (now the Community Peacemaker Team) as an unarmed accompaniment worker.

While there, she witnessed firsthand the struggles of asylum seekers. On the way to the United States, caravans would stop at safe houses. The last one in Mexico was located one and a half miles from the port of entry at the Arizona border. From there, they would go directly to the port of entry in groups of 20 where they would wait, sometimes up to five days, to tell their credible stories of fear to an immigration officer.

Because it is vital for asylum seekers to be present at the port of entry when their number was called, they would sleep on pallets outside the port for several days, Naar-Obed said. On these pallets, individuals were exposed to the elements and were vulnerable to being attacked by the drug cartels operating in the area.

Naar-Obed and others would accompany these individuals to a nearby welcome center where they could get clothing, take a shower and whatever necessities they needed. If permitted to cross the border, the asylum seeker is given one year to provide documents proving that they were being persecuted in their country of origin, Naar-Obed said. Those documents must be notarized through the government of their home country. Sometimes, that’s an easy task, she said, but in other cases, it is nearly impossible–especially if it is the government that is the persecutor.

While waiting for their final determination from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, asylum seekers are placed with sponsors, such as the Hildegard House community, which includes Naar-Obed and her partner, Greg Boertje-Obed.

Continue reading at CatholicWorker.org to learn how Hildegard House works to create safe spaces for new arrivals in Duluth.

After Grants Pass, What’s Next for L.A.’s Homeless Population?

“The ink was not yet dry on the Supreme Court’s decision in Grants Pass v. Johnson when a handful of Los Angeles City Council members sought clarity and counsel on how they could leverage this decision, which deems constitutional the further criminalization of poverty and punishment of its victims,” writes Matt Harper in the August issue of the L.A. Catholic Worker's newspaper, the Catholic Agitator. The LACW was one of dozens of organizations to file an amicus brief with the Court.

Drawing on conversations with Shayla Myers, an attorney with the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles, and the Los Angeles Community Action Network (LA CAN), Harper traced the city’s long history of “legislative punishing of the poor,” arguing that the goal of such policies has long been to sanitize the city for investment, real estate development, and high-end consumption. Despite community pressure and legal settlements, meaningful infrastructure improvements like permanent housing and hygiene facilities remain lacking, he said. Instead, the city focuses on disruptive street cleaning, the seizure of personal property, complex public camping regulations, and temporary housing programs that don’t offer long-term solutions. He cited programs like Mayor Karen Bass’s “Inside Safe” initiative, saying it only breaks up encampments without ensuring stable, long-term housing for those displaced.

Harper’s analysis was written before Gov. Gavin Newsom’s executive order directing state agencies to begin clearing homeless encampments.

As Los Angeles prepares for events like the 2026 World Cup and the 2028 Olympics, Harper warns of potential new tactics to displace and harm the city's most vulnerable residents. Noting the Los Angeles Catholic Worker’s previous successes litigating against the city, he promised that “our city council will have to get through us if they want to pass a new ordinance to be able to enforce Grants Pass. Rest assured, if they try, we are ready to fight them every step of the way.”

He continued:

And while we may be in a different place than communities like Grants Pass, we know we are a part of a movement that recognizes our shared interest with that community, and with many communities in fights that look very different from the ones we are in. Anyone struggling against the criminalization of poverty and the disposal of vulnerable people is part of us. As we return to the drawing board, we do so clear that we are not alone.

Read the entire analysis at CatholicWorker.org.

A Catholic Worker in the Heart of Appalachia

THE ROUNDUP

About 50 interfaith demonstrators descended on the headquarters of Citigroup in New York City on Tuesday, including Liam Myers of the New York Catholic Worker. The demonstration blocked access to the building for about 40 minutes, according to coverage by EarthBeat, and resulted in the arrest of about 24 people. The protest was part of the Summer of Heat on Wall St. Faith Week and a larger effort by faith groups to pressure Citigroup to stop funding the fossil fuel industry. Myers told EarthBeat that his faith calls him “to be on the side of the oppressed” and that justice for the poor and justice for the Earth are inseparable.

The two self-described “old-timers” at the Denver Catholic Worker are now actively planning their retirement for spring or summer 2025 “while we're still competent enough to do it,” the pair write on the community’s updated listing at CatholicWorker.org. “Our desire for our current guests to continue to be sheltered and cared for is now leading us in the direction of merging with another established community in Denver which is remarkably similar to us in values, mission and lifestyle. We'll keep you posted as our discernment evolves.” See the Denver Catholic Worker listing at CatholicWorker.org for more details and contact information.

The Bitterroot Valley Catholic Worker community is newly listed in the Catholic Worker Directory at CatholicWorker.org. The community cares for a garden and orchard on four acres of land and volunteers at homeless shelters in the city of Missoula. Some members also participate in antiwar resistance.

“While the Schaeffer-Duffys were on pilgrimage in Spain, my wife Sam and I house-sat here on Mason Street,” writes Brian (no last name provided) in the August/September issue of The Catholic Radical, newsletter of the Saints Francis & Thérèse Catholic Worker in Worcester, Massachusetts. “We’re both on a journey of our own toward starting a Catholic Worker farm and eco-village in central Massachusetts called Makarioi (from the Greek word that opens all the Beatitudes).” Claire Schaeffer-Duffy opens her piece about her and Scott’s Camino Santiago pilgrimage with the provocative line, “There is something oddly macabre about walking close to 500 miles with a pack on your back, and sleeping in foreign villages, towns, and cities just to see the burial site of a beheaded saint.” Read the rest of the issue here.

Catholic Workers in Kenya call one another rafiki, a Swahili word that means “friend,” and live a simple lifestyle in an intentional community called Boma, a Swahili word connoting home and spiritual values, according to the updated CatholicWorker.org listing for Christian Friends of Mentally Ill. The community, previously known as the Catholic Friends of Mentally Ill, is comprised of people suffering from mental illness and their allies and serves the mentally ill population. Read a profile of the community at CatholicWorker.org.

“I can sit in the chapel and be aware that God is there,” Johannes Maertens told the Polish publication Tygodnik Powszechny in a recent profile interview. “However, it is difficult to change your life while sitting in church, but living with someone who is different from you is challenging. It teaches me something about myself and how I relate to God.” Maertens is a Benedictine monk and community member with the London Catholic Worker. The profile details his winding spiritual journey, his founding of the Maria Skobcova Catholic Worker for refugees in Calais, France, and his continued work on behalf of refugees in London. You can read the article at the publication website; if you don’t read Polish, use your browser’s extension or online tools to get a workable translation.

World BEYOND War has given the 2024 David Hartsough Lifetime Individual War Abolisher Award to Susan Crane, the Redwood City (California) Catholic Worker currently serving a seven-month prison sentence in Germany as a result of her participation in a nonviolent protest at a German military base where the U.S. military keeps nuclear weapons. The award was presented virtually on July 22. Read more at World BEYOND War.

“I’m starting a new life in a different country,” Mohammed Salah, a community member at the Des Moines Catholic Worker, told Iowa Public Radio for a recent profile. Selah met his wife, Julie Brown, another DMCW member, while the two were volunteering with Community Peacemaker Teams in Iraqi Kurdistan; they married in 2017, but it took another five years for him to be admitted to the U.S. Read or listen to the story of his journey and life at the Des Moines Catholic Worker at Iowa Public Radio.

With cities increasingly using zoning ordinances to restrict charitable activities, some Catholic Worker communities are turning to federal laws that protect religious freedom, writes Vern R. Walker in the June/July issue of The Catholic Worker, the newspaper of the New York Catholic Worker. New Haven’s Amistad Catholic Worker House, for instance, is invoking a federal statute, the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000 (RLUIPA) in its ongoing conflict with the city over its backyard tiny home village for unhoused people. But the community faces several legal hurdles, Walker writes, not the least of which is proving that RLUIPA covers religiously motivated acts of hospitality.

The Dorothy Day Catholic Worker will commemorate the 79th anniversary of the U.S. nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with prayer vigils at the Pentagon and the White House. On Tuesday, August 6, 2024, from 7 to 8 AM, the group will gather in the Pentagon Designated Protest Zone on the southeast side of the building, accessible via the South exit from the Pentagon Metro station. A second vigil will take place on Friday, August 9, from noon to 1 PM, outside the White House on Pennsylvania Avenue's north side. These events will honor the victims of the bombings and others affected by nuclear weapons, including hibakusha, Pacific islanders, Native Americans, downwinders, and others impacted by nuclearism, while calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

“We left Venezuela together, having faith in God that we would arrive at our destination. The lack of basic necessities and the organized delinquency in our country obliged us to go out, fleeing, leaving behind our loved ones and a part of our lives.” As the situation in Venezuela deteriorates, read the first-person account of one Venezuelan family’s harrowing journey to the United States in the newspaper of the Houston Catholic Worker.

“Bar Crawl Radio's Alan Winson and Rebecca McKean of New York City (population 7,931,147) visited our Catholic Worker Farm in Maloy, Iowa (population 22) and recorded a tour of our gardens, livestock and of our little town,” writes Brian Terrell of Strangers and Guests Catholic Worker. “We are grateful for their time with us and their understanding that this beautiful place on earth and the life we have made here are not an escape from the world's problems.” Listen to the podcast here.

Speaking of podcasts, the Coffee with Catholic Workers podcast recently released episodes touching on end-of-life care, afterschool care at the Hartford Catholic Worker, foster care at the Loaves and Fishes Catholic Worker, and more. We will be featuring many of these episodes in upcoming issues of Roundtable, but in the meantime, you can listen to them on YouTube.

CALENDAR

August 5 | Virtual event

The Harry Murray Sessions: On the Hospitality of Dorothy Day and Jacques Derrida – Catholic Worker Movement

August 7 | Virtual event

The Long Loneliness Virtual Study Group

August 10 | Vandenberg Space Force Base, California

CW Memorial & Action at Vandenberg Space Force Base

September 6-7 | Chicago, Illinois

Peter Maurin Conference

September 12-15 | Sugar Creek, Iowa

Midwest Catholic Worker Gathering

October 4-6 | St. Francis Catholic Worker, Chicago, Illinois

Catholic Worker National Gathering

A FEW GOOD WORDS

To Sit Under One’s Own Fig Tree

by Dorothy Day, in the September 1947 Catholic Worker

Last month on my way home from church one day I was enchanted to see little fig trees and potted herbs being sold along the curb, for fifty cents apiece. So now in my window on the fire escape there is a delightfully fragrant bush of basil, two kinds, one the large leaf variety such as you find in cans of tomato paste, and the other the fine. Now every dish, even to the plain whole wheat pancake which we sometimes make for breakfast, can be garnished with a bit of chopped basil. The fig tree is to delight the eye and the imagination. There are even two little figs growing on it. All over the east side in the Italian section, wherever there is a bit of dirt for a backyard, the Italians have their fig trees carefully corseted in straw in the winter, and cherished fondly in the summer. To sit under one’s own fig tree! Even the proletariat, the property-less, keep dreaming of this heaven. “A land flowing with milk and honey!” “Of the fruit of their corn and wine and oil they are multiplied. In peace in the selfsame I will sleep and I will rest. For thou, O Lord, singularly has settled me in hope.”

Roundtable covers the Catholic Worker Movement. This week’s Roundtable was produced by Jerry Windley-Daoust, Renée Roden, Joan Bromberek, Monica Welch, and Scarlett Ford.

Roundtable is an independent publication not associated with the New York Catholic Worker or The Catholic Worker newspaper. Send inquiries to roundtable@catholicworker.org.

https://austrian-institute.org/en/blog/catholic-social-teaching-out-of-touch-with-economic-thought/

Some commusings to think about?

http://www.edwardfeser.com/unpublishedpapers/socialjustice.html