Carter and the Catholic Worker

Also: Hildegard House prepares deportation defense; Hisaye Yamamoto and the CW; Holy Innocents Pentagon protest; St. Louis CW hits the streets as cold snap approaches; and Dorothy on having a baby.

Catholic Workers Often Clashed with Carter

Shortly after Jimmy Carter was elected president, I wrote him a letter. I don’t recall the specifics, except that I wrote it in crayon and it featured lots of red hearts. I was seven, and a month or two later, the White House sent me a nice letter in response.

I have felt warmly toward President Carter ever since, although my image of him is probably overly rosy, shaped mostly by his post-presidential activities promoting affordable housing, public health in developing countries, and human rights.

Catholic Workers of the era may have a more complicated view of his legacy.

Take longtime Catholic Worker Frank Cordaro (Des Moines Catholic Worker), for instance, who famously (or infamously) disrupted a November 1979 White House event to protest the Carter administration’s nuclear weapons policy.

As Cordaro tells it (and you really need to check out his account, which is pretty hilarious), he somehow got invited to a White House event promoting Senate ratification of the SALT II treaty, which aimed to curb the nuclear arms race. Many Catholic Workers, Cordaro included, thought the treaty didn’t go far enough. He was particularly concerned that it did nothing to address the United States’ first strike doctrine, in which the U.S. reserves the right to use nuclear weapons even absent the launch of a nuclear attack from another nation.

Cordaro showed up at the White House event with ashes tucked into a plastic bag hidden in his pants. After several other officials spoke to the treaty (what Cordaro called “baloney” and “blasphemy”), President Carter took the stage amid applause and TV cameras.

After a brief internal debate over the wisdom of his plan (and a request to Bishop Thomas Gumbleton, seated nearby, for prayers), Cordaro stood, unbuttoned his pants to retrieve the ashes, and stepped into the aisle. The crowd froze. Turning to face the audience, Cordaro declared, ““Friends! SALT II is a lie, and Jimmy Carter’s lying to us. These ashes represent the dead from the first strike.”

Unfortunately, the ashes had clumped together while they were in his pants, so instead of the dramatic sprinkling of ashes that he intended, clumps of ash hit his head. Meanwhile, his pants—which he had unbuttoned to retrieve the ashes—began to slip down.

The crowd’s anger turned to laughter as Cordaro was escorted away by the secret service. But his message got across:

Of course, no one heard me. No one heard a word I said, but it was all on the TV. It picked up everything, and later on, a woman from Iowa got up and said, “Mr. President, I like that young man from Iowa whom you had dragged out of here. We’re concerned how anyone in the peace movement can support a treaty that allows for first-strike weapons.”

A quick perusal of the archives of The Catholic Worker reveals a litany of Carter administration policies that drew the ire of CWers, mostly related to military spending and foreign policy.

In fact, Cordaro wasn’t the only Catholic Worker to confront President Carter publicly. In the October 1977 issue of The Catholic Worker, Dan Mauk wrote about

our friends from Jonah House in Baltimore, who were recently arrested for disrupting a church service in Washington attended by President Carter. Though this idea of “disruption” has been debated and questioned by members of our community, and probably by many others, I saw the action in light of what St. James wrote. As the pastor stepped into the pulpit to begin his sermon, those of Jonah House stood and read, “Did not Jesus mean what He said when He taught us to love our enemies? And did He not live what He said? . . . Christians cannot love their enemies and still threaten them with nuclear death...” It’s certainly a difficult matter, trying to act in love with a just anger—the result, a church service “disrupted.” But how do we deal with a picture happening so often, where the Church and the Cross lead the war—a situation I find not merely disruptive, but contrary to the Gospel-message of peace.

Thank goodness these Catholic Workers were willing to offer a prophetic witness to the Gospel (and to basic sanity, when it comes to ending the world.) And thank goodness, too, for the goodness of people like Jimmy Carter—complicated, messy people who do their best to be humble and merciful and kind in a world where power and cruelty all too often seem to be the coin of the realm.

—Jerry

P.S. For another Catholic Worker take on President Carter, check out Steven Saint Thomas at The Catholic Farmer: My Favorite President: Jimmy Carter’s Moral War.

THE ROUNDUP

Featured

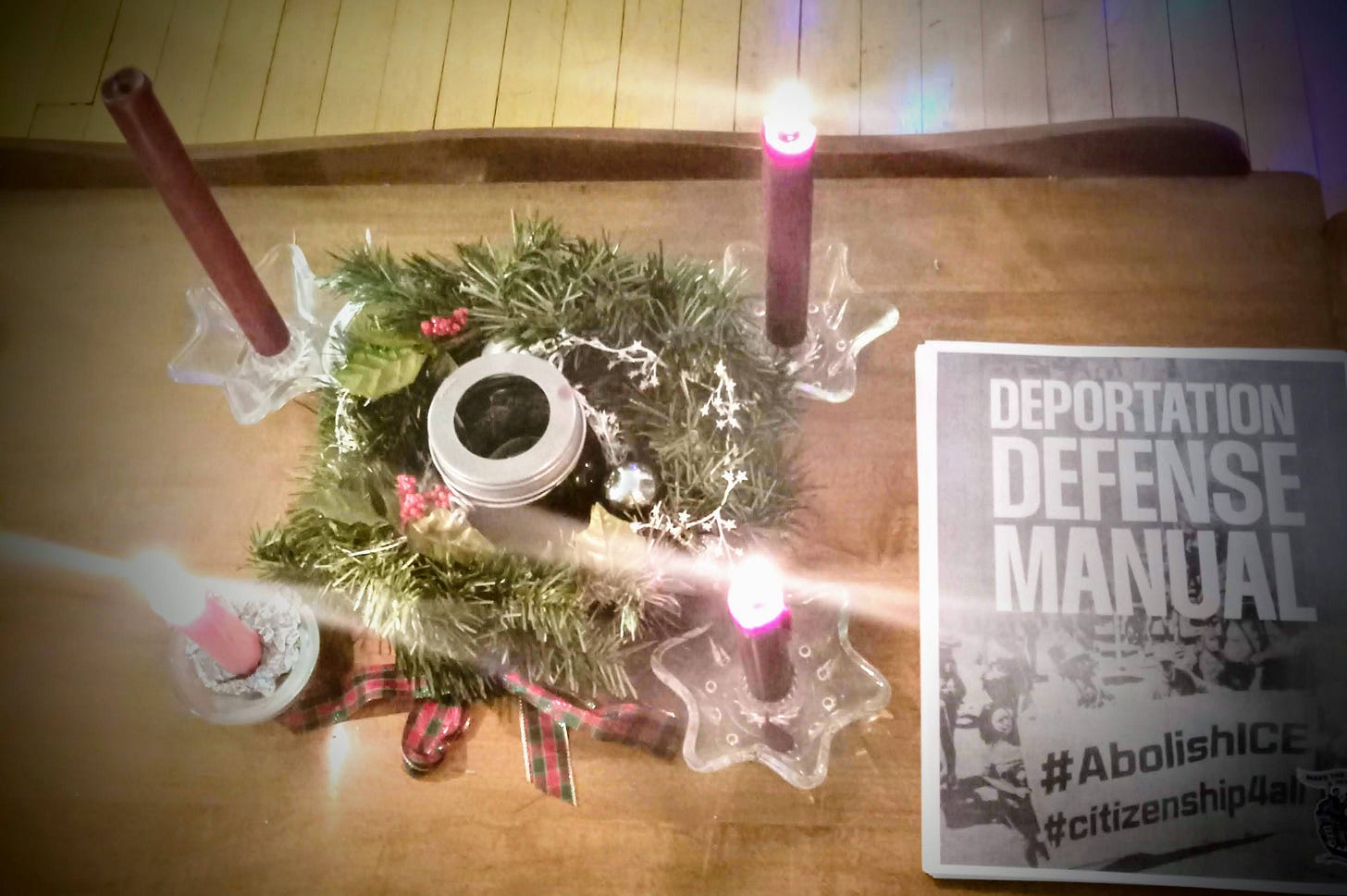

Hildegard House Prepares Deportation Defense in Duluth

The Hildegard House Catholic Worker in Duluth, Minnesota, is mobilizing efforts to support migrants amid potential large-scale deportations under the new presidential administration. The community is organizing a "Safe and Connected" program and drawing from resources like New York's Deportation Defense Manual to develop protection plans. An upcoming meeting, "Safe and Prepared: A Meeting for the Twin Ports Migrant Community and Supporters," will bring together hosts, sponsors, direct supporters, and local migrants to strategize contingency plans in case of human rights violations. The initiative reflects broader efforts nationwide to protect vulnerable communities. Read Michele Naar-Obed’s essay about these efforts, “Our War at Home,” in Thursday’s CW Reads.

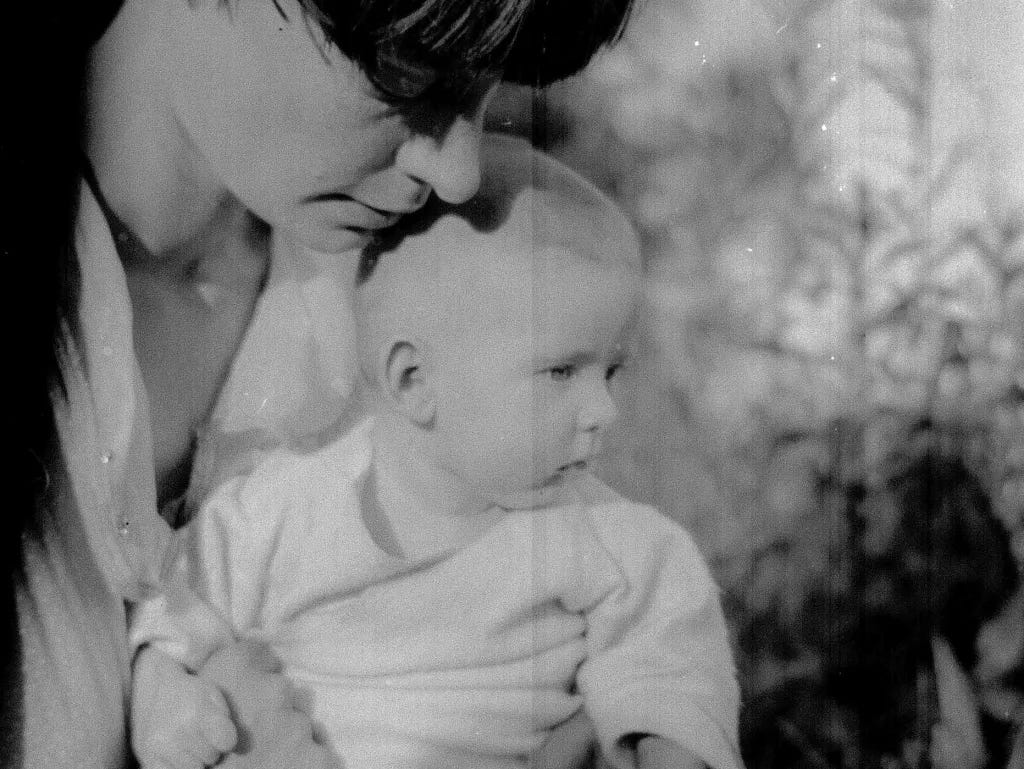

Heartbreak at the Des Moines Catholic Worker

The Des Moines Catholic Worker community is grieving the recent deaths of three individuals deeply connected to its work and mission. Baby Amy, the infant daughter of long-term guests Nic and Alex, tragically passed away from sudden infant death syndrome on October 16. Her death left the Manning House community in profound mourning, with the family now returned to their home in Honduras. Additionally, two early members of the Des Moines Catholic Worker, Richard Cleaver and Michael Sprong, passed away within weeks of each other. Both were pivotal in shaping the community's legacy, with Richard mentoring others on Catholic Worker principles and Michael dedicating decades to activism and hospitality. “This was one of the hardest times I have ever had at the Des Moines Catholic Worker,” Frank Cordaro wrote in an essay for the community’s latest newsletter; you can read it in Thursday’s CW Reads.

Hisaye Yamamoto’s Short Stories Were Informed by Her CW Experience

Hisaye Yamamoto (1921–2011), the Japanese American writer known for her short stories reflecting themes of internment, trauma, race, and faith, was profoundly influenced by her experience at the Catholic Worker. That’s the focus of a Dec. 20 piece by Anthony Shoplik in Commonweal, “‘The Best Type of Catholic There Was.’” The daughter of Japanese immigrants, her childhood in California was marked by displacement due to anti-Asian land laws and her family's internment during World War II. After her release, she won acclaim as a columnist at the Los Angeles Tribune. In 1952, she won a prestigious writing fellowship at Stanford University, but she turned it down and instead moved to Peter Maurin Farm with her adopted son. Dorothy Day praised Yamamoto for her work ethic and quiet resilience, though Yamamoto's writings later acknowledged the difficulties of communal life. In later life, Yamamoto identified as a "Christian anarchist," embracing the Catholic Worker’s emphasis on decentralized community living, pacifism, and mutual support. Shoplik argues that her Catholic Worker experience is evident in her writing, particularly in “Epithalamium,” a fictionalized account of life within the community. More broadly, Shoplik says the Catholic Worker movement's principles were central to Yamamoto's political and literary contributions, even as she maintained a complex relationship with Catholicism. Read the essay at Commonweal.

CW Community News & Newsletters

Marking the Feast of the Holy Innocents at the Pentagon

Twelve people held a nonviolent witness outside the Pentagon on Friday, Dec. 27, to mark the Feast of the Holy Innocents. The witness included Gospel readings, reflective songs like the Coventry Carol, and excerpts from a sermon by Rev. Munther Isaac, alongside poetry and a litany for the day. The event concluded with a symbolic act of resistance, as the group stepped outside the designated protest area to recite the Lord's Prayer, prompting the police to redirect pedestrian traffic as employees entered the building. The witness was organized by the Dorothy Day Catholic Worker in Washington, D.C., and drew participants from the Little Flower Catholic Worker, Southern Life Community, Franciscan Action Network, and Pax Christi Metro DC-Baltimore. “In these perilous times we need now, more than ever, to live and proclaim the Gospel of Nonviolence and resist the ongoing massacre of the Holy Innocents today,” organizer Art Laffin said in an email statement.

St. Louis Catholic Worker Joins Winter Outreach Efforts

The St. Louis Catholic Worker is partnering with St. Louis Winter Outreach to protect unhoused individuals during dangerously cold nights, with temperatures expected to drop into the low 20s and snow in the forecast. Volunteers assist in street outreach by offering emergency shelter and distributing blankets, gloves, and other essentials to help the city's most vulnerable survive the harsh weather. The Catholic Worker community coordinates Monday night shifts as part of this life-saving effort. For more information, email StLouisCatholicWorker@gmail.com or text Theo at 314-320-5129.

CWers Join Protest of Lancaster’s Plans to Sweep Encampment

James Murphy of the St. Martin de Porres Catholic Worker (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania) and Sean Domencic of the Rechabite Catholic Worker (Lancaster, Pennsylvania) joined 35 members of Lancaster Stands Up Friday as they protested the planned sweep of a homeless encampment by the city of Lancaster. State Rep. Izzy Smith-Wade-El, who represents the southern end of the city, joined the protest for an hour. “If your first goal is getting people houses, sweeps don’t do that,” she told Lancaster Online. Domencic urged the city to adopt “right to rest” policies; Mayor Danene Sorace noted that shelter beds were available and that it was imperative to get campers inside in advance of cold weather. Read more at Lancaster Online.

Terrell Ordered to Report to German Prison

Brian Terrell of the Strangers and Guests Catholic Worker in Maloy, Iowa, has been ordered to report to prison in Wittlich, Germany, on February 26 to serve a 15-day sentence for a 2019 anti-nuclear protest. Terrell, along with fellow Catholic Workers Susan Van der Hijden and Susan Crane, cut through a security fence at the Büchel air base, where U.S. nuclear weapons are stored under a NATO agreement. During their protest, the group unfurled a banner declaring nuclear weapons illegal and described the base as a "crime scene." Reflecting on the act, Terrell noted the larger crime of nuclear proliferation, calling it a threat to humanity.

Waterloo Catholic Worker Seeks Live-In Volunteers

The Waterloo Catholic Worker is looking for volunteers to join its intentional faith-based community, offering free room and board in exchange for about 15 hours of work per week. Volunteers assist with a community soup kitchen near downtown Waterloo, which serves meals three evenings a week. Responsibilities include hospitality, meal prep, and light chores. For more information, contact Rose at 319-232-3177.

Norfolk Catholic Worker Vigils at NATO Base, Submarine Plant

“Since January of 2022, as Russian troops massed on Ukraine’s border, a handful of Catholic Workers and friends have held a regular vigil for peace a long block from NATO Allied Command Transformation, headquarters to the alliance’s warfare development arm,” writes Steve Baggarly in the Fall/Winter 2024 issue of Simplicity, newsletter of the Norfolk Catholic Worker. “We stand on a median with signs: Russia & NATO out of Ukraine; Negotiate Don’t Escalate and No One Wins a Nuclear War.” Read his articles about the community’s witness at the NATO base and the Huntington-Ingalls Newport News Shipbuilding plant, which builds parts for nuclear submarines, in Simplicity.

News from NYCW’s Peter Maurin Farm

The December issue of The Catholic Worker features an update by T. Christopher Cornell, the son of longtime CW peace activist Thomas Cornell, on his life at Peter Maurin Farm since his father passed away in 2022. After dealing with serious heart troubles, he is farming again; he also reports on the departure of longtime residents Else and Ralph Dowdy. Also: In the cover story, "Bread & Roses y Mi Abuela," Yarilynne Esther Regalado recounts her grandmother Ramonita Rodriguez’s journey from poverty in Puerto Rico to building a life in Lawrence, Massachusetts, where she participated in the historic 1912 "Bread and Roses" labor strike. And in "Rise St. James in NYC," Bernard Connaughton reports on a protest at Citigroup headquarters in Manhattan on September 23, where 31 activists were arrested for blocking the entrance to oppose Citibank’s continued financing of the fossil fuel industry. The Catholic Worker is only available in print; contact the New York Catholic Worker about a subscription.

DD Catholic Worker Farm Hopes to Raise $29,000 for New Initiatives

The Dorothy Day Catholic Worker Farm (Harveys Lake, Pennsylvania) is hoping to raise $29,150 for new projects in 2025, including a food pantry in an underserved area of Scranton, expanded egg production, a new trailer, expansion of fenced pasture, and a new access road. Additionally, plans include twice-yearly theology retreats focusing on Ressourcement/Communio teachings, fostering faith and discussion. Find out more at the community’s website.

Kensington Nativity

CW in the News

Karl Meyer Named Nashvillian of the Year for Lifelong Activism

Veteran CWer Karl Meyer, 87, has been named Nashvillian of the Year by Nashville Scene for his decades of social justice work and recent protests against Tennessee’s anti-camping law targeting unhoused individuals. A prominent figure in the Catholic Worker Movement since the 1950s, Meyer’s activism spans anti-war protests, death penalty opposition, and the creation of affordable housing initiatives through his Nashville Greenlands project. Alongside his partner, Pam Beziat, Meyer has transformed homes in North Nashville into an affordable housing network, fostering a community of young advocates. Lindsey Krinks, co-founder of Open Table Nashville, credits Meyer’s mentorship with shaping her advocacy work: “It’s really important for community organizers and activists to have intergenerational connections and relationships, because we can learn from folks who come before us,” Krinks told the magazine. “We have so much to learn from people like Karl.” Read the in-depth profile at the Nashville Scene website.

NCR’s Patty McCarty Remembered for Play about Dorothy Day

Patty McCarty, a former editor at the National Catholic Reporter, passed away on Christmas morning at the age of 93. In a recent article, NCR editor emeritis Thomas Fox remembered McCarty’s meticulous editing and vibrant faith; he also noted that she was deeply influenced by Dorothy Day, whom she met twice, once interviewing her as a student journalist at Marquette University. Those encounters eventually led McCarty to write a two-act play about Day’s life, This Other Love, in 1994. The play explored Day’s complex spiritual journey, highlighting her doubts, her relationship with Forster Batterham, and her eventual embrace of Catholicism. The play was rediscovered and staged in 2017, fulfilling McCarty’s dream of seeing her work brought to life on stage. To read more about McCarty's legacy, visit National Catholic Reporter.

Mark Your Calendar

Mar. 5 Protest of U.S. Obstruction of Disarmament Treaty

The Atlantic Life Community (ALC) is organizing a protest in New York City during the 3rd Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (3MSP) on March 5, 2025. Held at the United Nations from March 3-7, the meeting seeks to advance global nuclear disarmament, though nuclear-armed states remain opposed. The ALC, alongside the War Resisters League and Veterans for Peace, will protest the U.S. role in obstructing disarmament efforts. Catholic Worker communities from New York, Ithaca, and Norfolk are among the organizers. For those interested in joining the protest or planning efforts, a virtual meeting will be held on January 7. For more details, contact Steve Baggarly of the Norfolk Catholic Worker.

WORDS FROM THE ELDERS

“Having a Baby: A Christmas Story”

by Dorothy Day; originally published in New Masses, June 1928, and reprinted in The Catholic Worker, Dec. 1, 1977

When I was in Mexico many years ago (in 1929!), my daughter Tamar was three years old. We were one day visiting Diego Rivera, whose beautiful murals were all over Mexico City. He looked at my daughter, saying, “I know this little girl. Your article ‘Having a Baby’ was reprinted all over the Soviet Union, in many languages. You ought to go over there and collect royalties.”

I had written the story for my old friend Mike Gold, who was editing the “New Masses” at the time (June 1928). While not yet a Catholic, I was firmly resolved to have my child baptized one.

She is now the mother of nine, and the grandmother of twelve! She has been spending a week with me, and has just returned to her home in Vermont. (Needless to say, she needs to get away from that tribe once in a while.) We had a delightful visit!

—Dorothy Day

December 1977

On Wednesday I received my white ticket, which entitled me to a baby at Bellevue. So far I had been using a red one, which admitted me to the clinic each week for a cursory examination. The nurse in charge seemed very reluctant about giving out the white one. She handed it to me, saying doubtfully, “You’ll probably be late. They’re all being late just now. And I gave them their tickets and just because they have them they run into the hospital at all times of the night and day, thinking their time is come, and find out they were wrong.”

The clinic doctors acted very much disgusted, saying, “What in the world’s the matter with you women? The wards are empty.” And only a week before they were saying, “Stall off this baby of yours, can’t you? The beds are all taken and even the corridors are crowded.”

The girl who sat next to me at the clinic that day was late the week before and I was astonished and discouraged to see her still there. She was a pretty, brown-eyed girl with sweet, full lips and a patient expression. She was only about eighteen and it was her first baby. She said, “Ma’am,” no matter what I said to her. She seemed to have no curiosity and made no attempt to talk to the women about her; just sat there with her hands folded in her lap, patient, waiting. She did not look very large, but she bore herself clumsily, childishly.

There was one Greek who was most debonair. She wore a turban and a huge, pink, pearl necklace and earrings, a bright dress and flesh-colored stockings on still-slim legs. She made no attempt to huddle her coat around her as so many women do. She had to stand while waiting for the doctor, the place was so crowded, and she poised herself easily by the door, her head held high, her coat flung open, her full figure most graciously exposed. She rather flaunted herself, confident of her attractions. And because she was confident, she was most attractive.

When I got home that afternoon, thinking of her I put on my ivory beads and powdered my nose. I could not walk lightly and freely, but it was easy to strut.

There was another woman who was late, a great, gay, Irish wench who shouted raucously as she left the doctor’s office, “The doctor sez they are tired of seeing me around and I don’t blame them. I rushed over three times last week, thinking I was taken and I wasn’t. They sez, ‘The idea of your not knowing the pains when this is your third!’ But I’m damned if I come in here again until they cart me in.”

So, when I was philosophically preparing myself to hang around a month, waiting for my child to knock on the door, my pains started, twelve hours earlier than scheduled. I was in the bath tub reading a mystery novel by Agatha Chrystie when I felt the first pain and was thrilled, both by the novel and the pain, and thought stubbornly to myself, “I must finish this book.” And I did, before the next one struck fifteen minutes later.

“Carol!” I called. “The child will be born before tomorrow morning. I’ve had two pains.”

“It’s a false alarm,” scoffed my cousin, but her knees began to tremble visibly because after all, according to all our figuring, I was due the next morning.

“Never mind. I’m going to the hospital to exchange my white ticket for Tamara Teresa”—for so I had euphoniously named her.

So Carol rushed out for a taxicab while I dressed myself haltingly, and a few minutes later we were crossing town in a Yellow, puffing on cigarettes and clutching each other as the taxi driver went over every bump in his anxiety for my welfare.

The driver breathed a sigh of relief as he left us at Bellevue, and so did we. We sat for half an hour or so in the receiving room, my case evidently not demanding immediate attention, and watched with interest the reception of other patients. The doctor, greeting us affably, asked which of us was the maternity case which so complimented me and amused Carol that our giggling tided us over any impatience we felt.

There was a Black woman with a tiny baby, born that morning, brought in on a stretcher. She kept sitting up, her child clutched to her bosom, yelling that she had an earache, and the doctor kept pushing her back. Carol, who suffers from the same complaint, said that she would rather have a baby than an earache, and I agreed with her.

Then there was a genial drunk, assisted in with difficulty by a cab driver and his fare, who kept insisting that he had been kicked by a large white horse. His injuries did not seem to be serious.

My turn came next, and as I was wheeled away in a chair by a pleasant, old orderly with whiskey breath, Carol’s attention was attracted and diverted from my ordeal by the reception of a drowned man, or one almost drowned, from whom they were trying to elicit information about his wife, whether he was living with her, their address, religion, occupation, and birthplace – – information which the man was totally unable to give.

For the next hour I received all the attention Carol would have desired for me – – attentions which I did not at all welcome. The nurse who ministered to me was a large, beautiful creature with marcelled hair and broad hips, which she flaunted about the small room with much grace. She was a flippant creature and talked of Douglas Fairbanks and the film she had seen that afternoon, while she wielded a long razor with abandon.

Abandon. Abandon! What did that remind me of? Oh yes, the suitor who said I was lacking in abandon because I didn’t respond to his advances.

Thinking of moving pictures, why didn’t the hospital provide a moving picture for women having babies? And music! Surely things should be made as interesting as possible for women who are perpetuating the race. It was comforting to think of peasant women who take lunch hours to have their children in, and then put the kids under the haystack and go on working in the fields. Hellish civilization!

I had nothing at home to put the baby in, I thought suddenly. Except a bureau drawer. Carol said she would have a clothes basket. But I adore cradles. Too bad I had been unable to find one. A long time ago I saw an adorable one on the east side in an old second-hand shop. They wanted thirty dollars for it and I didn’t have the thirty dollars, and besides, how did I know then I was going to have a baby? Still I wanted to buy it. If Sarah Bernhardt could carry a coffin around the country with her there is no reason why I couldn’t carry a cradle around with me. It was a bright pink one—not painted pink, because I examined it carefully. Some kind of pink wood.

The pain penetrating my thoughts made me sick to my stomach. Sick at your stomach, or sick to your stomach? I always used to say “sick to your stomach” but William declares it is “sick at your stomach.” Both sound very funny to me. But I’d say whatever William wanted me to. What difference did it make? But I have done so many things he wanted me to, I am tired of it. Doing without milk in my coffee, for instance, because he insists that milk spoils the taste of coffee. And using the same kind of tooth paste. Funny thing, being so intimate with a man that you feel you must use the same kind of tooth paste he does. To wake up and see his head on your pillow every morning. An awful thing to get used to anything. I mustn’t get used to that baby. I don’t see how I can.

Lightning! It shoots through your back, down your stomach, through your legs and out at the end of your toes. Sometimes it takes longer to get out than others. You have to push it out then. I am not afraid of lightning now, but I used to be. I used to get up in bed and pray every time there was a thunder storm. I was afraid to get up, but prayers didn’t do any good unless you said them on your knees.

Hours passed. I thought it must be about four o’clock and found that it was two. Every five minutes the pains came and in between I slept. As each pain began I groaned and cursed, “How long will this one last?” and then when it had swept over with the beautiful rhythm of the sea, I felt with satisfaction “it could be worse,” and clutched at sleep again frantically.

Every now and then my large-hipped nurse came in to see how I was getting along. She was a sociable creature, though not so to me, and brought with her a flip, young doctor and three other nurses to joke and laugh about hospital affairs. They disposed themselves on the other two beds but my nurse sat on the foot of mine, pulling the entire bed askew with her weight. This spoiled my sleeping during the five minute intervals, and, mindful of my grievance against her and the razor, I took advantage of the beginning of the next pain to kick her soundly in the behind. She got up with a jerk and obligingly took a seat on the next bed.

And so the night wore on. When I became bored and impatient with the steady restlessness of those waves of pain, I thought of all the other and more futile kinds of pain I would rather not have. Toothaches, earaches, and broken arms. I had had them all. And this is a much more satisfactory and accomplishing pain, I comforted myself.

And I thought, too, how much had been written about child birth—no novel, it seems, is complete without at least one birth scene. I counted over the ones I had read that winter—Upton Sinclair’s in The Miracle of Love, Tolstoi’s in Anna Karenina, Arnim’s in The Pastor’s Wife, Galsworthy’s in Beyond, O’Neill’s in The Last Man, Bennett’s in The Old Wives’ Tale and so on.

All but one of these descriptions had been written by men, and, with the antagonism natural toward men at such a time, I resented their presumption.

“What do they know about it, the idiots,” I thought. And it gave me pleasure to imagine one of them in the throes of childbirth. How they would groan and holler and rebel. And wouldn’t they make everybody else miserable around them. And here I was, conducting a neat and tidy job, begun in a most businesslike manner, on the minute. But when would it end?

While I dozed and wondered and struggled, the last scene of my little drama began, much to the relief of the doctors and nurses, who were becoming impatient now that it was almost time for them to go off duty. The smirk of complacence was wiped from me. Where before there had been waves, there were now tidal waves. Earthquake and fire swept my body. My spirit was a battleground on which thousands were butchered in a most horrible manner. Through the rush and roar of the cataclysm which was all about me I heard the murmur of the doctor and the answered murmur of the nurse at my head.

In a white blaze of thankfulness I knew that ether was forthcoming. I breathed deeply for it, mouth open and gasping like that of a baby starving for its mother’s breast. Never have I known such frantic imperious desire for anything. And then the mask descended on my face and I gave myself to it, hurling myself into oblivion as quickly as possible. As I fell, fell, fell, very rhythmically, to the accompaniment of tom toms, I heard, faint about the clamor in my ears, a peculiar squawk. I smiled as I floated dreamily and luxuriously on a sea without waves. I had handed in my white ticket and the next thing I would see would be the baby they would give me in exchange. It was the first time I had thought of the child in a long, long time.

Tamara Teresa’s nose is twisted slightly to one side. She sleeps with the placidity of a Mona Lisa, so that you cannot see the amazing blue of her eyes which are strangely blank and occasionally, ludicrously crossed. What little hair she has is auburn and her eyebrows are golden. Her complexion is a rich tan. Her ten fingers and toes are of satisfactory length and slenderness and I reflect that she will be a dancer when she grows up, which future will relieve her of the necessity for learning reading, writing and arithmetic.

Her long, upper lip, which resembles that of an Irish policeman, may interfere with her beauty, but with such posy hands as she has already, nothing will interfere with her grace.

Just now I must say she is a lazy little hog, mouthing around my nice full breast and too lazy to tug for food. What do you want, little bird? That it should run into your mouth, I suppose. But no, you must work for your provender already.

She is only four days old but already she has the bad habit of feeling bright and desirous of play at four o’clock in the morning. Pretending that I am a bone and she is a puppy dog, she worries at me fussily, tossing her head and grunting. Of course, some mothers will tell you this is because she has air on her stomach and that I should hold her upright until a loud gulp indicates that she is ready to begin feeding again. But though I hold her up as required, I still think the child’s play instinct is highly developed.

Other times she will pause a long time, her mouth relaxed, then looking at me slyly, trying to tickle me with her tiny, red tongue. Occasionally she pretends to lose me and with a loud wail of protest grabs hold once more to start feeding furiously. It is fun to see her little jaw working and the hollow that appears in her baby throat as she swallows.

Sitting up in bed, I glance alternately at my beautiful flat stomach and out the window at tug boats and barges and the wide path of the early morning sun on the East River. Whistles are blowing cheerily, and there are some men singing on the wharf below. The restless water is colored lavender and gold and the enchanting sky is a sentimental blue and pink. And gulls wheeling, warm grey and white against the magic of the water and the sky. Sparrows chirp on the windowsill, the baby sputters as she gets too big a mouthful, and pauses, then, a moment to look around her with satisfaction. Everybody is complacent, everybody is satisfied and everybody is happy.

About us. Roundtable covers the Catholic Worker Movement. This week’s Roundtable was produced by Jerry Windley-Daoust and Renée Roden. Art by Monica Welch at DovetailInk. Roundtable is an independent publication not associated with the New York Catholic Worker or The Catholic Worker newspaper. Send inquiries to roundtable@catholicworker.org.

Subscription management. Add CW Reads, our long-read edition, by managing your subscription here. Need to unsubscribe? Use the link at the bottom of this email. Need to cancel your paid subscription? Find out how here. Gift subscriptions can be purchased here.

Paid subscriptions. Paid subscriptions are entirely optional; free subscribers receive all the benefits that paid subscribers receive. Paid subscriptions fund our work and cover operating expenses. If you find Substack’s prompts to upgrade to a paid subscription annoying, email roundtable@catholicworker.org and we will manually upgrade you to a comp subscription.