For Dorothy Day, ‘All Is Grace’

The truth behind the ever-evolving myth of the 'Coffee Cup Mass' finds resonance with Dorothy's admiration of St. Thérèse; essays by Brian Terrell and Rosalie Riegle explain the deep connection.

Good morning, and happy feast of St. Nicholas! You’re reading a bonus issue of CW Reads, the long-read edition of the Roundtable newsletter. This morning, we have a double feature for you.

First up: People love to tell the story of Dorothy Day’s “Coffee Cup Mass,” in which she is supposed to have personally reverenced a coffee cup that had been used as a chalice during a Mass at the Catholic Worker. But how much of that story is true? As the story evolves with each retelling, it risks overshadowing the deeper truths of Dorothy’s spirituality, Brian Terrell writes. In today’s essay, he explains what this enduring myth gets wrong—and why the reality of Dorothy’s faith offers a more profound lesson than any legend.

Then, Rosalie Riegle reviews Dorothy Day: Spiritual Writing, a new collection edited by Robert Ellsberg. In her review, Rosalie finally finds the deep connections between Day and her spiritual hero, St. Thérèse of Lisieux.

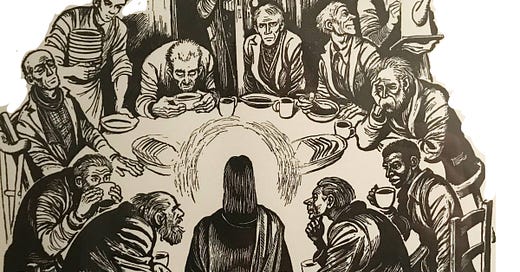

Dorothy Day certainly believed that God was present in the sacraments; but, as today’s authors point out, she also believed that it did not end there. Instead, the real presence of God in the Eucharist was meant to transform us, enabling us to find that same presence in the ordinary, mundane matter of everyday life—and, crucially, in one another, especially those of us who have been broken by suffering. As Rosalie writes, Dorothy “learned that if we do everything for and in the presence of God, our entire life becomes prayer.”

What the Myth of the Coffee Cup Mass Gets Wrong—and Why It Matters

by Brian Terrell

People love to tell the story of Dorothy Day’s “Coffee Cup Mass,” but how much of it is true? As the story evolves with each retelling, it risks overshadowing the deeper truths of Dorothy’s spirituality. Brian Terrell explains what this enduring tale gets wrong—and why the reality of Dorothy’s faith offers a more profound lesson than any legend.

Dorothy Day may have been prescient when she wrote “We have seldom been given the saints as they really were, as they affected the lives of their times — unless it is in their own writings.” Stories naturally shape how we remember the heroes and saints who inspire us. Sometimes, though, stories can stray from the truth when they eclipse, distort and even challenge the very words of those heroes and saints. The so-called “Coffee Cup Mass,” a tale attributed to Dorothy Day, is one such story that in its various contradictory versions reflects more of the storyteller’s assumptions than the reality of Dorothy’s life and spirituality. By viewing this enduring myth through Dorothy’s own account of it, we are given a more profound understanding of her vision of holiness and the sacred.

In the late 1990s, Jim Forest began telling the story of how Dorothy Day responded

when a priest close to the community used a coffee cup for a chalice at a Mass celebrated in the soup kitchen on First Street. She afterward took the cup, kissed it, and buried it in the backyard. It was no longer suited for coffee — it had held the Blood of Christ. I learned more about the Eucharist that day than I had from any book or sermon.

Despite the fact that in Dorothy’s March 1966 column, which Jim cited to support the story, Dorothy herself said, “I was not there when this happened,” and even after, in a 2016 blog post, Jim acknowledged, “I didn’t see her actually bury the cup,” the alleged buried coffee cup continues its hold on the popular imagination. Like a child’s game of telephone, with each retelling, the story picks up new and increasingly dramatic details, with the later iterations bearing little resemblance to the story Jim told in the first place.

The recent graphic novel Dorothy Day: Radical Devotion by Jeffry Odell Korgen, illustrated by Christopher Cardinale, speaks of the “legends about her holiness” that “began to circulate” late in Dorothy’s life. Two different versions of the “one prominent story” that they call “Dorothy Day and ‘The Coffee Cup Mass’” are offered for consideration.

The first version is among the most extreme in circulation. A priest celebrates Mass at the Worker house, throws a fit after being confronted by Dorothy for using a coffee cup for a chalice, and flings it into a trash can. Dorothy reverently genuflects and crosses herself before the trash can, retrieves the cup, and buries it, the story goes. In the alternate version of the legend, one that I had never heard before, it is Dorothy herself who throws a fit after returning home and discovering that Fr. Dan Berrigan had offended the rubrics with a coffee cup on the altar while she was away. This one has a happier ending, when a member of the community makes Dan a gift of a golden chalice, putting all things right. “Which story is true?” we are then asked.

“Probably this one,” the authors suggest, referring to the second, more prosaic one. “But the other story,” they say, “is ‘true’ in the sense of communicating Dorothy’s spirituality — she wanted to change the world, not the Mass.”

In traditional hagiography, the legends of the saints matter less in terms of whether an event in a saint’s life actually happened and more in terms of whether the story tells a deeper truth. But Dorothy Day (1897–1980) is not St. Ursula, who was martyred along with 11,000 anonymous virgins in the 4th century. Despite the efforts of some, Dorothy is not lost in the mists of legend. Dorothy wrote about the event when it happened, and Jim remembered it differently more than thirty years later. Neither version of the story offered in Dorothy Day: Radical Devotion agrees with what Dorothy or Jim reported. No cup was buried, no one has seen Dorothy venerating the Blood of Christ in a trash can, and certainly no one at the Catholic Worker gave Dan Berrigan a gold chalice. Neither version is true, and what is least true of all is that either one communicates anything of Dorothy’s spirituality.

“Which story is true?” What is true is that, on reflection, Dorothy Day realized that using a coffee cup for a chalice at Mass was no big deal.

Writing about it in March 1966, when Dorothy said, “I am afraid I am a traditionalist, in that I do not like to see Mass offered with a large coffee cup as a chalice,” she was speaking of her aesthetics, not defining her spirituality.

“And yet — and yet,” she continued, “perhaps it happened to remind us that the power of God did not rest on all these appurtenances with which we surround it. That all over the world, in the jungles of South America and Vietnam and Africa — all the troubled, indeed anguished spots of the world — there Christ is with the poor, the suffering, even in the cup we share together, in the bread we eat. ‘They knew Him in the breaking of bread.’”

In that same column, Dorothy restated the Catholic Worker’s long commitment to reforms of the Mass promoted by the liturgical movement (“We had our communion procession and even the altar facing the people, as far back as 1937,” she wrote), changes deemed essential if Catholics were to “change the world.”

For some Dorothy Day “fans,” including some of the good bourgeois Catholics whom Dorothy seemed to enjoy scandalizing at times, the buried coffee cup represents the pinnacle of her achievement, the act of atonement for her radicalism that sealed her sanctity. For many of these, the buried coffee cup is only part of a larger false narrative. No one these days promotes the buried coffee cup with more vigor than Bishop Robert Barron, who always adds one curious detail, insisting that before burying the cup, Dorothy smashed it with a hammer!

Jim Forest lived at the New York Catholic Worker in the 1960s. I was there a decade later. When I knew Dorothy in the five years before her death, every celebration of the Mass we attended together in our houses was as informal as it was reverent. Many who identify as “traditionalist” Catholics today measure devotion to the Eucharist precisely on one’s attention to what Dorothy came to see as the “appurtenances with which we surround it.” Judged by the contemporary standards of some who venerate her now, Dorothy, in real life, might not measure up as a very devout Catholic.

Seven years ago, in 2017, responding to questions I was being asked, I wrote an article that was published in The Catholic Worker and in The National Catholic Reporter as “True lesson of Dorothy Day’s ‘Coffee Cup Mass.’” This was my conclusion:

If the lesson of this story is not, as some say, that the line between the things that are sacred and those that are profane must never be crossed and that the rules around the sacraments and worship cannot be flouted, then what is it? What is the lesson Day would have us learn?

She often paraphrased and made her own the words of St. John Chrysostom: “If you cannot find Christ in the beggar at the church door, you will not find him in the chalice.” She was also a student of St. Benedict, who in his Rule for Monasteries insisted that all of the utensils of the monastery be regarded “as if they were the sacred vessels of the altar.”

What Day learned from the “Coffee Cup Mass” was that the ceramic cup from which the homeless Christ sips her morning coffee is no less holy and no more profane than the gold chalice that holds Christ’s blood in the form of wine at the Mass: “There Christ is with the poor, the suffering, even in the cup we share together, in the bread we eat.”

What Dorothy Day Learned from St. Thérèse of Lisieux

A Review of Dorothy Day: Spiritual Writings, edited by Robert Ellsberg

Dorothy Day changed my life! In fact, she’s still changing it, many years later. Dorothy Day: Spiritual Writings (edited by Robert Ellsberg, published by Orbis Press) changed it still further. Ellsberg has arranged some of her many writings by subject, beginning with “The Word Made Flesh” and continuing through eleven sections, ending with “Revolution of the Heart.” All of her writings are good, and the sections of her diary where she laments her sins were especially interesting. But this time, I was struck by her frequent references to the book she wrote about St. Thérèse of Lisieux.

I confess I had never before considered it, as I didn’t see what she and Dorothy Day had in common, but this time, it hit me! She loved that saint and even wrote a book about her. Ellsberg titled the fifth chapter “The Little Way,” and in it, Day discusses why she wrote a book about St. Thérèse. Dorothy read the autobiography of St. Thérèse of Lisieux when she was first converted and was not impressed with this “little flower” who died in an obscure French convent when she was only twenty-four. At that time, Dorothy preferred spectacular saints such as St. Joan of Arc. But that changed as she gained experience as a leader of the Catholic Worker movement. She came to see that each sacrifice, done in the name of love and in the presence of God—St. Thérèse’s teaching—would increase love throughout the world. Even sacrifices that appeared ineffective would be like small pebbles that cause ripples capable of transforming the world.

Finally, Dorothy spent some years writing a book about St. Thérèse, showing that everything we do matters and that damping down our resentment and disappointment (daily occurrences in any house of hospitality) is truly transformative. I realized that these teachings can work in families and other communities as well.

St. Thérèse died in 1897 and was canonized very soon afterward, in 1925. As Dorothy read more about her, she realized that it was the workers who canonized her and spread her fame through many books and shrines.

St. Thérèse frequently said, “All is grace,” and Dorothy began to feel it as well. She wrote a book about her, Thérèse, and began to live her teachings, offering up all the thousands of distractions that happen when one serves the lonely, poor, and decrepit, as she did. Dorothy learned to offer up her suffering, as Thérèse did. Thérèse suffered mightily in her illness, and Dorothy came to rejoice in what she called her petty suffering. Thus, she grew closer to Thérèse and strove to love everyone, without regard for their goodness.

As Dorothy wrote about her, she came to believe that the spiritual weapons we all have at our disposal are more powerful than nuclear bombs. She learned that if we do everything for and in the presence of God, our entire life becomes prayer. So I will definitely read her Thérèse and hope it brings me closer to God.

About us. Roundtable covers the Catholic Worker Movement. This week’s Roundtable was produced by Jerry Windley-Daoust and Renée Roden. Art by Monica Welch at DovetailInk. Roundtable is an independent publication not associated with the New York Catholic Worker or The Catholic Worker newspaper. Send inquiries to roundtable@catholicworker.org.

Subscription management. Add CW Reads, our long-read edition, by managing your subscription here. Need to unsubscribe? Use the link at the bottom of this email. Need to cancel your paid subscription? Find out how here. Gift subscriptions can be purchased here.

Paid subscriptions. Paid subscriptions are entirely optional; free subscribers receive all the benefits that paid subscribers receive. Paid subscriptions fund our work and cover operating expenses. If you find Substack’s prompts to upgrade to a paid subscription annoying, email roundtable@catholicworker.org and we will manually upgrade you to a comp subscription.