Honoring the Legacy of Gustavo Gutiérrez

The Father of Liberation Theology commemorated in the pages of the January-February 2025 The Catholic Worker

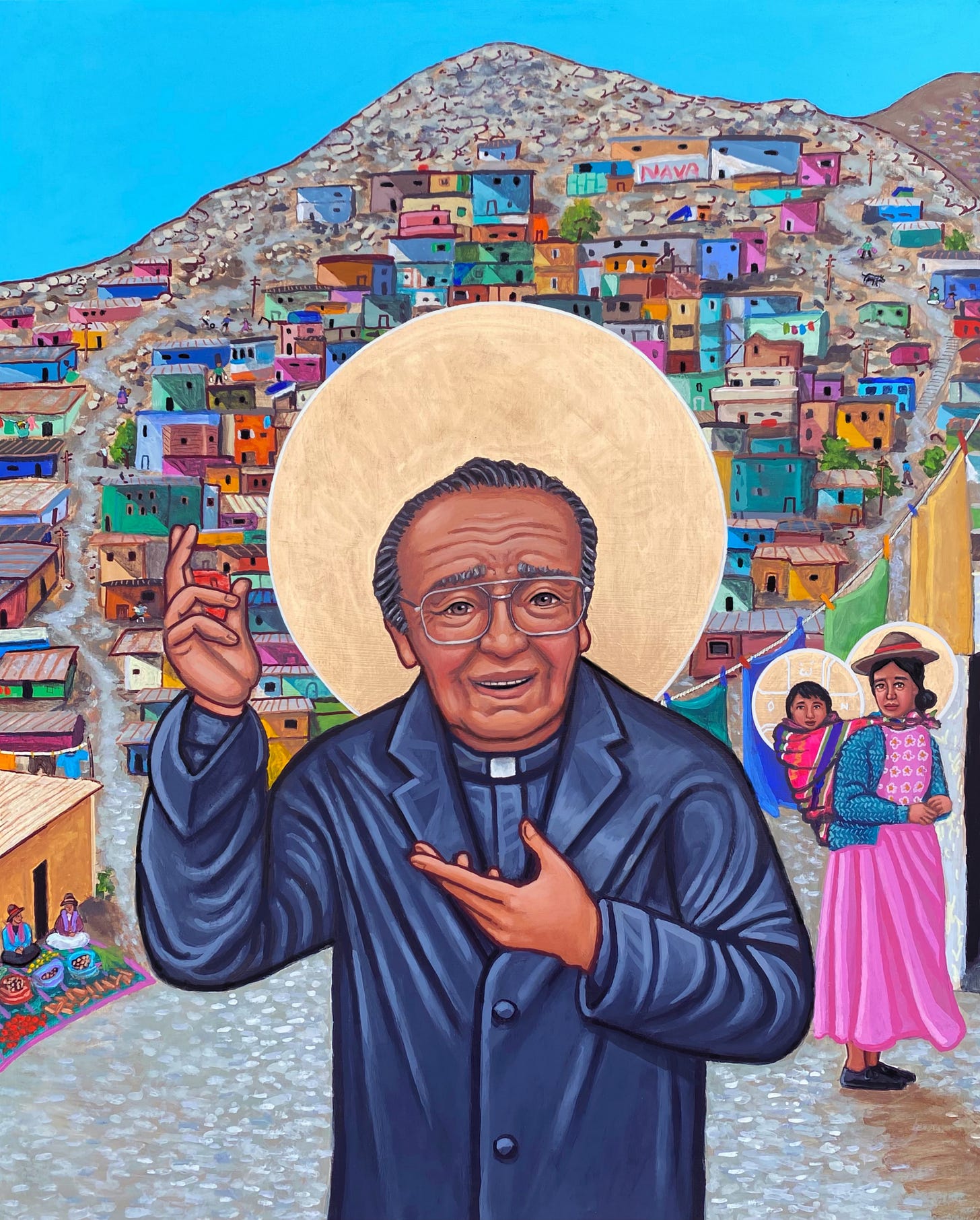

Gustavo Gutiérrez, a Dominican priest and highly influential theologian died on October 22, 2024, at the age of 96. Gutiérrez was widely known as “the father of liberation theology,” a theology that—like Dorothy Day’s own lived theology—was concerned with both the spiritual and material needs of the poor and marginalized, and was criticized for being too close to Communism.

As Liam Myers articulates in our reflection for today:

“Latin American liberation theology teaches us that to love the poor is to have a preferential option for the poor as God does.”

Understandably, Gutiérrez was an inspiration for many Catholic Workers, and his writings were frequently quoted in the pages of The Catholic Worker. He even visited the newspaper’s offices, nearly fifty years ago.

Gutiérrez spoke at a Friday Night Meeting at the New York City Catholic Worker in 1976, where he marveled at his unusual audience. Unusual in that, he noted, their “disagreement with violent means was as strong as their opposition to oppression.”

In the most recent issue of The Catholic Worker, Maryhouse community member Liam Myers shares the continued echos of Gutierrez’s theology in his life at Maryhouse.

Gustavo Gutiérrez Presente!

by Liam Myers

I grew up going to St. Joseph’s Church in Grafton, Wisconsin. This is where I went to Sunday school, where I was confirmed, where I received my sacraments over the years. I have especially fond memories of the Easter Vigil at St. Joe’s where I would lead “We Are Marching” on my saxophone at the end of the Mass. I still return for service when I visit family and am always greeted by familiar faces.

For over thirty years, St. Joe’s parish has had a mission to a village in the Dominican Republic, Los Toros, where they serve the local community through assisting with education, housing and other needs. I remember being at Mass with my aunt Susan, who once went with the church to Los Toros. I must have been in middle school at the time. Toward the end of the Mass, they made an announcement about the church’s mission to Los Toros. Someone spoke of the poor conditions in which the people live and that we could help by joining the mission or by donating. I remember crying after Mass, as we were walking out. I was so upset.

Years later I was up late in the library reading In The Company of the Poor for theology class when I came across this quote: “Unless we agree that the world should not be the way it is... there is no point of contact, because the world that is satisfying to us is the same world that is utterly devastating to them.”

These words [from the book co-written by Paul Farmer and Gustavo Gutiérrez] helped me process the experience I had in Mass, hearing the announcement for Los Toros. It articulated the gap between my life, where all my basic needs were accounted for, and the lives of those living in poverty, who saw the world as utterly devastating. It took me years after reading this quote to realize that I was confronted with two options: I could continue to live a good and satisfying life without taking the cries of those who suffer into my heart and feet, or I could chart a new way forward and live into the message that liberation theologians like Gustavo Gutiérrez, through his writings, opened up for me.

Hailed as the father of Latin American liberation theology, Gutiérrez (1928–2024) is a giant in the theological world. Ask any Catholic who has a heart for justice about what theologies have guided and formed them and many will point to liberation theology or name it as a touchstone.

After his passing, many Catholic groups shared his quotes on social media. One stood out to me: “You say you love the poor? Name them.” This moral clarity resonates with the philosophy of personalism which inspires the CW, that we must know one another in order to get along with, and to build community with, and to love one another. Gutiérrez rightly points out that we cannot love the poor in the abstract, but only through tangible relationships.

Latin American liberation theology teaches us that to love the poor is to have a preferential option for the poor as God does. This started for me as putting the needs of others before myself. For example, I would prioritize the needs of the poor before my own needs when it came to voting, making purchases, or anything else. Then, as I began to deepen my life within community, I realized that any decision about how I was to proceed in life could not take account of my own concerns alone, I had to hold the concerns of those I love and the cries of the least of these. Living in community makes it clear: we share our lot with each other. But even if you do not live in community, this is still true. Whether we recognize it or not, when one part of the body suffers, we all do. Liberation theology helps us recognize the Gospel call which explicitly rejects the individualist ideology that a neoliberal state encourages us to adopt.

Gutiérrez articulates that “we are talking here about the journey of an entire people and not of isolated individuals.” He constantly states that liberation is the task of a whole people. While striving towards abundant life for all, Gutiérrez also knew that one had to confront death daily.

The problem that Gutiérrez faced most clearly, within his context, was that of people living in such extreme poverty. When describing the situation in Latin America, Gutiérrez writes in We Drink From Our Own Wells:

“The real issue in this situation is becoming increasingly clear to us today: poverty means death. It means death due to hunger and sickness, or to the repressive methods used by those who see their privileged positions being endangered by any effort to liberate the oppressed. It means physical death, to which is added cultural death, inasmuch as those in power seek to do away with everything that gives unity and strength to the dispossessed of the world. In this way those in power hope to make the dispossessed an easier prey for the machinery of oppression.”

In order for us to take Gutiérrez’s life seriously we must understand and adapt his theology within our context in the global north.

Our capitalist-driven consumer society is obsessed with life, so much so that it hides death at all costs. We see this clearly in NYC, as poverty (which means death) is criminalized. It is in effect illegal to exist as a person in NYC if you do not have money or a bed to sleep on [see article by Logan Marrow in the same issue of The Catholic Worker].

Not only do the police constantly sweep encampments where people experiencing homelessness are living, but it’s also nearly impossible to use the bathroom anywhere in the city without first making a purchase. This is a city that hides those living in poverty in order to hide death. In Capitalism and the Death Drive, Byung-Chul Han writes, “To affirm life means also to affirm death. Life that negates death negates itself.”

How can we affirm death in our city thereby allowing ourselves to see the reality in which the poor spend their lives?

In Loaves and Fishes, Dorothy Day wrote about poverty as a “strange and elusive thing,” saying that she both condemns and advocates poverty. She wrote, “We need always to be thinking and writing about it, for if we are not among its victims its reality fades from us.”

Dorothy knew that in order for us to understand poverty, to understand death, we must live in recognition of our closeness to it. This life is in opposition to the promises of our capitalist society: that we can buy more, hoard more, and build ourselves so high up on our wealth so that we would never fall to our death—or to the street. This capitalist dream rests on complicity with suffering.

Here we realize that the death found in poverty, which Gutiérrez articulates, is not a passive one. As we deny our proximity to death by consuming more and more in the Global North we perpetuate systems of poverty in the Global South. Our denial of death removes us from contact with life which prevents us from working towards mutual flourishing. By not recognizing that death is a part of life, we are killing.

Within Gutiérrez’s context, people were and are faced with death due to material conditions, therefore they seek life through a transformation of said conditions. In the US context, we are promised false life within mass consumption, hoarding and wealth. Therefore, we must die to our wealth in order to aid in transforming these conditions which lead to global poverty. We must die not only to our wealth but to the status quo, we must die to the logic of war and we must die to our prejudice. All of this is so that we can live anew with Christ. As Gutiérrez wrote, “Jesus is not to be sought among the dead: He is alive.”

This theology, when taken to heart, impacts how we live our life. A mentor of mine at Union Theological Seminary helped me to understand this more clearly. Dr. Cláudio Carvalhaes is an eco-liturgical liberation theologian who taught me to slow down and pay attention to the birds, as a necessary first step in any liberative praxis.

In his book, How Do We Become Green People and Earth Communities?, Carvalhaes articulates the importance of allowing a liberative theology to impact your daily life:

“Let us lift up sub- jugated knowledges, barbarian knowledges, women’s knowledges, Black knowledges, Asian knowledges. I want to know more about my great-grandmother who was a nurse/xaman than I will ever know about Calvin.”

In seeking to lift up subjugated knowledge, our Integral Ecology Circle here at Maryhouse has read from people of color and Indigenous communities as we seek to broaden our understanding of integral ecology. We recently discussed an essay by James Cone entitled, “Whose Earth Is It Anyway?” Our circle resonated with Cone’s critique of white environmentalism, and we discussed the importance of having an ecosystem of organizing.

Some of us shared a growing feeling that capitalism is the core issue, and that we can never truly heal our Earth within this mucky, decaying system. We then highlighted this quote from the essay: “Only when white theologians realize that a fight against racism is a fight for their humanity will we be able to create a coalition of blacks, whites and other people of color in the struggle to save the earth.”

I often struggle when I am called upon to share about the Catholic Worker. How can I convey in an hour that our humanity is bound together? How can I invite people to begin to truly encounter their neighbor? Well, I’m not sure how to do any of that, so I usually start by asking a question: What is your favorite soup? Many say chicken noodle, some broccoli cheddar. Others share soups that emerge from their cultures like tom kha or sancocho. Some say that they do not like soup. I then recall Annie Dillard who said, “How you spend your days is how you spend your lives,” and proclaim that at the CW our days are spent living the Works of Mercy. This includes feeding the hungry, one ladle of soup at a time.

My answer to the question? It depends on what delicious soup Trevor or Amy has made recently or on what ingredients are in our industrial fridge in St. Joe’s basement. It is a treat when I find leeks, likely dropped off by Michael from the local CSA, and I make potato leek soup. Cathy says you don’t need to add any other ingredients because those two make music together. I like to add coconut milk.

When we serve soup we enter into the space between, the space which occupies the border of the here and now and the not yet realized. This simple act, to show love where love is not, is a radical one. To give food to those the world deems as undeserving is to act as Christ would. This is God’s preferential option, that seeks only the desires of the least of these through Christ.

Liam Myers is a freelance writer, an adjunct professor of religious studies at Iona University, and member of the Catholic Worker Maryhouse in NYC. At the Catholic Worker, Liam serves as an associate editor on the newspaper, and is the founder of the community's Instagram page: @nycatholicworker.

Liam finds beauty in the everyday; in a slow walk through Washington Square Park, in a good bowl of potato garlic soup, and in playing his saxophone with friends.

Art by Kelly Latimore at Kelly Latimore Icons. Thank you to Kelly for letting us use this beautiful icon! Read about Kelly’s process of creating the icon—and purchase a copy of your own—here.

“It is not enough to describe poverty, but to try to know the reasons for this poverty,”

About us. Roundtable covers the Catholic Worker Movement. This week’s Roundtable was produced by Renée Roden and Jerry Windley-Daoust.

Roundtable is a publication of catholicworker.org, independent of the New York Catholic Worker or The Catholic Worker newspaper. Send inquiries to roundtable@catholicworker.org.

Subscription management. Add CW Reads, our long-read edition, by managing your subscription here. Need to unsubscribe? Use the link at the bottom of this email. Need to cancel your paid subscription? Find out how here. Gift subscriptions can be purchased here.

Paid subscriptions. Paid subscriptions are entirely optional; free subscribers receive all the benefits that paid subscribers receive. Paid subscriptions fund our work and cover operating expenses. If you find Substack’s prompts to upgrade to a paid subscription annoying, email roundtable@catholicworker.org and we will manually upgrade you to a comp subscription.