Immigration and Idolatry

As Pope Francis clarifies the meaning of Christian love for the vice president, three stories of women who turned to a merciful God during their harrowing journey to the United States.

On Monday, Pope Francis released a letter to the U.S. Catholic bishops clarifying the Church’s teaching on immigration “in these delicate moments that you are living” in the United States. Not that the bishops needed any lessons on the matter; many of them have already issued statements in response to the new administration’s immigration policies and rhetoric.

Instead, the statement seemed more pointedly addressed to Vice President J.D. Vance. The V.P. had earlier defended the administration’s policies by invoking the theological principle of ordo amoris, the right ordering of love, to suggest that properly ordered love focuses on family first, then neighbors, then one’s nation, and lastly, foreigners. That argument had been supported and amplified by Catholic influencers on the right.

In his letter, though, Pope Francis corrected that interpretation, saying that “Christian love is not a concentric expansion of interests that little by little extend to other persons and groups.” Rather, mature Christian love “builds a fraternity open to all, without exception,” as revealed in the parable of the Good Samaritan. “This is not a minor issue,” the Pope wrote:

an authentic rule of law is verified precisely in the dignified treatment that all people deserve, especially the poorest and most marginalized. The true common good is promoted when society and government, with creativity and strict respect for the rights of all — as I have affirmed on numerous occasions — welcomes, protects, promotes and integrates the most fragile, unprotected and vulnerable. This does not impede the development of a policy that regulates orderly and legal migration. However, this development cannot come about through the privilege of some and the sacrifice of others. What is built on the basis of force, and not on the truth about the equal dignity of every human being, begins badly and will end badly.

The Pope concluded by exhorting Catholics and people of good will to resist discriminating against “our migrant and refugee brothers and sisters” and to practice fraternity and solidarity instead.

The response from the Christian right was about what you would expect: not a conversion so much as a doubling down, with various influencers citing everything from the Bible to the pope’s supposed hypocrisy (Vatican City is walled) as justification for the administration’s sweeping deportation campaign.

As important as it has been for the pope and bishops to reaffirm the most basic tenets of the Gospel (e.g., love of neighbor transcends partisan and national allegiances), Catholic Workers know from personal experience that it is mainly through personal encounter with Christ in the guise of the Other that our hearts are softened and, in time, converted to love.

The Houston Catholic Worker has always had a good intuition for this truth, and frequently prints first-hand accounts from migrants in the pages of its newspaper. Today, we share three of these stories with you.

Notice, as you read these harrowing accounts, how often these women humble themselves before God—how many times they call on God to have mercy on them and their loved ones. Notice, too, how the God whose mercy they seek differs from the god that the vice president and his partisans invoke.

Louise Zwick and Noemí Flores insightfully developed this theme—the anti-immigrant fervor’s relationship to idolatry—in an essay that originally appeared in the April - June 2024 issue of the Houston Catholic Worker. We’re reprinting it here, for those who might be interested.

Let’s continue to pray for a true conversion of hearts around this issue.

—Jerry

I Escaped with My Life

by Anonymous

originally published in the January - March issue of the Houston Catholic Worker

Hello. This is an immigrant from Venezuela. I came with my 9-year-old son. Our story begins on March 10, 2024, when we decided to leave Venezuela leaving our family - my mother, father and sister. We arrived in Colombia on the 15th at Necocli, a place to get through the jungle. The jungle, called the Darien, is where we had to pay to pass through, and where we had to walk two and a half days to get to Panamá, where everyone arrives.

During those days that I came with my son, my sister, and my nephew, we started the jungle crossing. We had to pass a mountain of fourteen hills where my sister stayed three hours behind. I would have to continue with my son alone. She stayed with the necessary things like food, water, and water purification pills. Thanks to my God, we were able to leave and continue walking to get out of that jungle that was very desperate without food, only the little that was given to us, with blisters on our feet and an endless road. Then, we continued without stopping until some native people came out. They touched people in order to get what they were looking for and my companions warned me with signs that I should not go there with my son. I went swimming through the river with a lot of current. One man told them to shoot me, but as God was with me, his gun could not detonate. When I was a little far away, I heard the shot.

We kept walking to get out of the jungle and the next day we were able to leave. I waited there for my sister who was further behind, and then we went to Panamá, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico, walking, asking for help and food. When we arrived in Guatemala the police stopped us to take money from us; and since we didn't have any, they touched our private parts to make sure we didn't have anything. When they saw that we had nothing, they let us go. We went to Mexico in order to get to Mexico City. After walking for various days, we stayed on the coast at a place called Puerto Escondido, where we slept in the street. We worked selling candies at the streetlights to be able to gather enough to continue to the city. Then, I worked at an Oxxo, a grocery store, begging for food and help. There, I slept with my son for approximately 2 weeks to be able to gather the money.

We continued to the city where I worked for seven and a half months to be able to gather all of the money I could for my CBP One appointment. After waiting, thanks to my God, we got our long-awaited appointment. We waited 19 days to be able to travel to the border of Hidalgo Reynosa and pass through to Texas.

When we arrived on November 16, I was kidnapped along with my son and another person who had an appointment. Upon arriving at the airport, I went to look for an Uber, some people grabbed us and took us in a car. From there they brought us to their bosses, where they asked us for three thousand dollars for my son and me, and if we didn’t pay, they would not release us. As the days went by, my family was able to raise 70% of the money, for which they sold everything they had. But they could not help me more. The men told me what they could do with me if no one could pay for me anymore. I clung to God and humbled myself, asking him to soften the man’s heart so that he would release me and my son. Since we had been left without food, without bathing, and without sunlight, when from one moment to the next, the guy called me and said, “I am going to let you go,” I saw the glory of God, I cried and hugged my son. I was released at the entrance of the bridge, they left me two blocks from the bridge, and as best I could, I ran and entered. Thanks to my God I was able to get through and I am in this wonderful place. I thank my God because this is the second time he has given me another chance at life.

A Tough Journey for Our Family

by Anonymous

originally published in the January-March 2022 issue of the Houston Catholic Worker

We left Venezuela together, having faith in God that we would arrive at our destination. The lack of basic necessities and the organized delinquency in our country obliged us to go out, fleeing, leaving behind our loved ones and a part of our lives. We were my husband, my son and I, but we were also accompanied by my sister-in-law, her husband and their two daughters.

As we began our journey, we headed to our sister Republic of Colombia. We arrived in the city of Medellin, then took a bus to Necoclí, with the thought that from that place we would take a boat to Panama City, but we were surprised to find that these trips were no longer made because Panama had closed its borders.

When we learned of this news, we asked how the journey was toward Capurganá, in order to go through the stretch that is the border between Colombia and Panama through a jungle called Darien. A part of our odyssey began from that moment. Thousands of Haitians wanted to cross in this same way. We had to wait from Wednesday to Saturday to board the boat that would carry us to the jungle.

When we arrived on this small island, we could see the enormous mountain that we thought to cross. We began to hear of the dangers we would face in crossing that jungle, which included rapes, attacks and mistreatment, even death. We were filled with terror, but we were already there and we had to continue our journey.

In that place there were many coyotes trying to lead people to cross. We went with one who inspired the most trust in us. Thus, we began our jungle journey. We can say that we found that day one of the most dangerous places where we had ever been.

Already on the first day walking and at the beginning of the first mountain, we could see a body on the side of the road. When we asked our guide about it, he said that the person had been bitten by a snake.

That first day we arrived at the first camp, and we said among ourselves that this was not so difficult, but in reality we had hardly started. On the journey we were with a large group in which there were persons of various nationalities, but the largest group were Haitians.

At dawn, the whole camp began to take apart their tent in order to begin walking again. This day we had to cross various hills. The guide told us we had to walk fast, because having children we always were falling behind the group and this day we had to go through what is called the Hill of Death. In these mountains there are always criminals. Our walk began and in the late afternoon we came to a river. We decided to rest and wait there for my sister-in-law and her family. When they arrived, we continued on.

We started to go up what would be the last mountain of the day, but in a few minutes, night began to fall. It was hard to distinguish the path. We started to hear noises of animals that come out at night and our fear grew. We had no flashlight and didn’t know where to walk. The mud made it very difficult, because many times our boots were completely buried. In this moment of desperation, we began to ask God to take care of us.

A moment later, a group of Haitians who were coming behind us caught up with us and passed us. But the leader of the group, upon seeing us with children and very desperate, decided to stay with us and accompany us. This man was very tall and big and carried a large flashlight that lit the way very well. He said that if we needed to rest we should do so, but our anxiety to arrive at the camp made us say no. Even though we were worn out, we only wanted to get there. At that moment two men armed with shotguns came down from the other side, coming back. We thought they would rob us, but they only said, “Go up, it’s only one more hour’s walk.

We walked about two hours and still had not arrived. We understood later that it was because we walked very slowly. But after three hours, we began to come down the mountain and we heard the voices of people. It was the camp. We arrived at 11:00 p.m. The Haitian man told us that we had arrived. He left us and we did not see him again. On the following day, we decided to look for him to thank him, but we did not find him.

We decided not to wait for my sister-in-law because we didn’t want anything to happen. We spoke with her so that she would try to walk faster.

The third day the mountains were steeper. A number of people helped us with our child. Each day the way was more complicated. The guide of our group abandoned us, only giving us directions that we should walk to the river, and once there we only had to walk to the edge in order to come to the first camp in Panama. The National Guard of Panama was there and they would help us. There would be no more big camps; we would only need to walk and camp when night fell.

On the road we could see things like women miscarrying and hear terrible things such as, “They killed so and so, they raped that woman, they robbed another.”

On the fourth day, my son and my husband began to feel bad, with vomiting and diarrhea from drinking contaminated water. Those were desperate days, because they could hardly walk. My husband had to carry our son on his back, since we had no food and nothing dry to put on my son or give him to eat. We only could ask people who were close by. We were there two days until we arrived at where there were canoes that took us to the camp,

We walked for another six days, but thanks be to God, although we were weak and somewhat ill, we arrived. My sister-in-law and her family arrived three days later. Her husband had hurt his foot. He almost lost it. T

We passed the second camp and came to the third, everyone in canoes. At the third camp my brother-in-law received medical attention for his foot and from there a bus left us at the border of Panama and Costa Rica. We rested there in the capital of Costa Rica.

Then we continued our journey to the border of Costa Rica and Nicaragua. We crossed in an irregular manner because they were charging $150 per person for documents and we did not have it. On the way, the police stopped us, but thanks be to God they let us go.

At the border of Nicaragua and Honduras we took a bus to Tegucigalpa. There in the capital of Honduras we had to wait for my brother-in-law who had a complication of an infection in his foot. They hospitalized him there for four days.

One night my husband went out to the market and someone tried to rob him with a pistol, but the hand of God has always been with us and is with us.

In Mexico in Tapachula we tried to take out documents to cross legally. But the time to wait for an appointment was very long, almost four months, so we decided to go on to the state of Tabasco. Mexican Immigration arrested us and we were five days in Immigration custody. Then they took us to a shelter with open doors.

A Surprise!

I began to feel bad with vomiting and feeling discomfort. My husband took me to a doctor and to our surprise, I was expecting a baby. But this came with complications. Because of injuries in the jungle, a hematoma had formed in my uterus.

We were twenty days in the shelter in Tabasco and sanitary conditions were bad. My son became ill with salmonella, which made us try to go out again and continue on our way. Two weeks later, we succeeded in arriving at the border at Acuña, full of uncertainty of what would come next.

We crossed the Rio Grande River. Three days later in the land of the United States, the Border Patrol took us to a border station. We were filled with fear of a possible deportation. We were processed and allowed to go. They took us to a church where they gave us food and clothing, because the Border Patrol had thrown everything away.

From the border we had to travel to Chicago. But the person who was going to receive us, because of family problems, could not receive us. We called Casa Juan Diego to see if they could receive us and the answer was positive. Now we are here, receiving love and attention from these marvelous persons. But we have a problem. At the Border Patrol, they did not process us correctly and even though all the people at Casa Juan Diego tried through many ways to obtain an “A” number for us, they could not.

Because of this, we have to travel to Chicago to go to Immigration there to check in and be more at peace. And so the story continues….

We Almost Didn’t Survive

by an anonymous Cuban refugee woman; originally printed in the Houston Catholic Worker, July-September 2021.

On the 19th of June of 2019 I left my country of birth to seek a better future for myself and my family. On that day I set out for Guyana. There I worked with my husband to maintain ourselves with food and housing. Many days we slept in the street as we had no money, but thanks be to God we achieved some economic stability thanks to a man who gave us cleaning work.

One fine day we decided to leave Guyana and try to get to the United States.

We left for Venezuela on the 24th of May of 2020 and there we were assaulted and our luggage was stolen. By the grace of God we arrived in Colombia where it was difficult but not impossible to survive.

In Colombia they almost killed my husband. He was beaten so badly that he couldn’t walk for three days, When he recovered sufficiently, we began the journey to Panama and this was the most difficult, bad and impossible to forget period of our whole trip. When we entered the jungle I thought we couldn’t survive as we had already heard many stories.

My husband and I and a group of Cubans entered the Darien jungle and walked for 11 days and got lost. We saw people die for lack of food and water. I was extremely sad to find bodies along the path. I was raped by a group of men on the 8th day of the journey. That is the worst thing that can happen to anyone and they held a pistol to my husband’s head while they raped me. He had to watch the awful things that they did to me. Then they stole everything we had and let us continue on the journey.

Thanks be to God we arrived at the camps in Panama. There they gave us medical attention, food and shelter and for 15 days we stayed waiting for money to be sent by a friend to be able to continue the journey

We continued on to Panama City and then reached the border of Costa Rica and continued on to Nicaragua and from there we quickly arrived at the border of Honduras.

In Honduras we were assaulted in Choluteca and the robbers only took our backpacks and some documents as we had hidden our money. But they beat us up and two of the group ended up in the hospital. It was there that I discovered that I was pregnant.

We continued on the journey to Guatemala and it was better there. Only the police asked for money to let us continue to travel.

I arrived in Mexico and I began the paperwork, but asylum was denied and I continued on to the United States. Arriving at the border of the United Sates and Mexico at Acuña we crossed the Rio Bravo and there I almost drowned but thanks to a boat from the United States I could get to shore and there I gave myself up to Immigration. They held us for two days and then sent us on to Casa Juan Diego. Thanks be to God and to Mrs. Louise who received us and for the volunteers who treat us super well and all the people who serve here. I thank God for the United States for letting me be here.

Idolatry in the Age of Migration

by Louise Zwick and Noemí Flores

originally published as “Reconstructing the Social Order Through the Works of Mercy in an Age of Migration” in the April-June 2024 issue of the Houston Catholic Worker

“Reactions vary to migration, sometimes bringing angry rhetoric and even hatred to uprooted peoples trying to survive in difficult times. The Church and the Catholic Worker Movement in its founders can show us a different way to respond.”

The fabric of our social order is being harmed and even destroyed today by the following of false gods. This includes the misuse of the Lord’s name in overt expressions of hostility towards groups in our society (especially migrants and refugees), extreme capitalism that increases the wealth of the few while many poorer people suffer, and by some expressions of Christian(?) nationalism which increase divisions.

During the Great Depression, Peter Maurin echoed the call of Pope Pius XI in the encyclical Quadragesimo Anno, asking us to help to reconstruct the social order. Much of that work remains to be done. And this may be a very special moment in which to do it. As Bishop Mark Seitz recently said in America magazine, “Migration is a privileged space in which the salvific mystery is being acted out.”

Misusing God’s Name

Those who say terrible things about refugees and migrants, those who defend unjust business practices in the name of God and freedom might meditate on the full text of the Commandments, especially the one against misusing God’s name. In an article entitled “An Impossible Fraternity?” in the Jesuit magazine La Civiltá Cattolica, Giovanni Cucci writes of the consequences of misusing God’s name:

Significantly, in the Decalogue, the prohibition against taking God’s name in vain is followed by the threat of punishment (“You shall not make wrongful use of the name of the Lord your God, for the Lord will not acquit anyone who misuses his name,” Exodus 20:7), which is not mentioned in the context of the other commandments, as if to reiterate the seriousness of such a transgression. To ‘misuse’ God’s name is to appropriate his name to justify self-interest, violence, murder, as can be associated with fundamentalism, terrorism and abuse of religious authority. The text distances itself from such perversions, denounces their seriousness, but at the same time also reveals their presence throughout history.

Misusing God’s name includes presenting to the world a “version” of Christianity which, while calling itself Christian, on close observation can be found not to be Christianity at all, but rather a “new” religion that promotes disparagement of others, encourages threats of violence and oppression, the identification of only one country with its religion, and the violation of other commandments as well: “You shall have no other gods before me. You shall not give false testimony against your neighbor. You shall not covet … anything that belongs to your neighbor.”

Some partisans of this other religion believe that persecution of refugees and migrants, the seeking of absolute power, lies, and even murder are justified.

They have omitted the knowledge that God created all people in His image and likeness and also have overlooked key passages in the New Testament.

The Commandments: Do Not Follow False gods, Do Not Worship Idols

The warnings from the prophets of the Bible that we not be taken in by false gods should give us all pause.

The Bible story from the prophetic book of Daniel about worshipping false gods is not as well-known as Daniel in the Lion’s Den, but it is significant for our times.

The story of Daniel tells of how the King of Babylon asked his friend Daniel why he did not worship the idol, Bel. revered and worshipped by the king and the Babylonians. The whole nation worshipped that god.

Daniel’s answer to the king was that he did not worship man-made idols, but only the Living God, who created heaven and earth. The king was surprised and said to Daniel, Do you not see that Bel is a living god? See how much he eats and drinks every day. We give him twelve bushels of flour and forty sheep to eat each night long with fifty gallons of wine.

Daniel laughed and said, Do not be deceived., O king. This is but clay and brass and it never ate or drank anything.

Through Daniel’s practical wisdom, the king learned that the seventy priests of Bel and their wives and children had been going through underground tunnels to get the food and eat it each night. The king put the priests to death, and gave the idol Bel over to Daniel, who destroyed it and its temple. (Daniel 14:1-22).

God Walks with his People Today

This earth is not our permanent home. As Servant of God Dorothy Day said, “We are on a pilgrimage to our real home” with the Lord, with the angels and saints.

In our life journey, for many it is hard to find a temporary home here on this earth. People in great numbers around the world are leaving their earthly homes. They are dying from hunger or violence. They are seeking a peaceful place to live for themselves and their families and practice their faith, if they are lucky enough to escape violence or destitution before it all overwhelms them. Often the social order not only does not support them, but makes their suffering worse.

Pope Francis, though, speaking of this journey, reminds us that the Lord, the Living God, is present with His people including migrants and refugees, as they walk:

During this journey, wherever people find themselves, it is essential to recognize the presence of God who walks with His people, assuring them of His guidance and protection at every step. Yet it is equally essential to recognize the presence of the Lord, Emmanuel, God-with-us, in every migrant who knocks at the door of our hearts and offers an opportunity for encounter.

Pope Francis, Message for the World Day of Migrants and Refugees, 2024

A major Instruction from the Vatican on The Love of Christ Toward Migrants.(2004) emphasized the scope of the reality of migration: “Today’s migration makes up the vastest movement of people of all times.” (Pontifical Council for the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant People, Erga migrantes caritas Christi (The Love of Christ Towards Migrants). Erga Migrantes, as many other documents from the Vatican and from local Bishops over the past decades, asks Catholics to address in a positive way the pastoral challenges of this reality.

Reactions vary to migration, sometimes bringing angry rhetoric and even hatred to uprooted peoples trying to survive in difficult times. The Church and the Catholic Worker Movement in its founders can show us a different way to respond. There is historical precedent.

A Previous Age of Migration

The historical period that used to be pejoratively referred to as the Dark Ages (300 to 1000 A.D.) was a time when peoples from different countries and cultures were on the move. Peoples organized into tribes came from many lands to parts of the Roman Empire and what is now Europe. Their journeys affected world history and geography in a major way.

Scholars remind us that those centuries should not be referred to as the Dark Ages, or an age of Barbarian Invasion, but instead, as the Age of Migration or the Migration Period.

During that time when the Roman Empire was breaking up and Germanic tribes migrated to Gaul and other parts of the Empire, there were certainly signs of darkness, violence, and changes in social realities. It turned out to also be an age of opportunity for followers of the Nazarene to respond creatively.

It is fascinating to read about the role of the Church in those centuries and especially that of the monasteries in bringing together peoples from different countries and different cultures, and actually reconstructing the social order. This happened especially from the example of the monks and monasteries who inspired the people.

There were heresies and divisions in the Church then as there are now, but goodness and the monastic ideal prevailed.

Monks, Monasteries, and the Reconstruction of the Social Order

Among the books Peter recommended in The Catholic Worker on this subject was Ireland and the Foundations of Europe by Benedict Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick’s book provides a substantive history of the reconstructive activity of Irish missionaries in Europe from the sixth century to the eleventh, flowing from the great ancient Irish civilization. “Abbeys and schools had arisen on the foundations of Roman ruins or the clearings in German forests. Pilgrims came and went in peace. Universities laid their foundations in the metropolitan centers.” The Irish monks carried the learning of their civilization with them as they journeyed to many different points in what is now Europe, often literally carrying their books on their backs as they walked.

“Stories are told of one or another digging his staff into the ground in the middle of a forest, where bears and other wild animals roamed, to begin his new monastic life there and relate to the people in the area.” (Benedict Fitzpatrick, quoted in Mark and Louise Zwick, The Catholic Worker Movement: Intellectual and Spiritual Origins.)

The Benedictines

St. Benedict, the founder of the Benedictine monks, lived from about 480 to 547 A.D. The connection between the Benedictines and the Catholic Worker is profound. Dorothy Day was a Benedictine Oblate. She often wrote about the Benedictine Rule which emphasized that “the Guest is Christ,” and that the monks should not treat a rich person with more respect than a poor person. Dorothy quoted John Henry Newman in The Catholic Worker in 1944 of how the Benedictines worked to restore the physical and social world that they found in ruins:

It was a restoration rather than a visitation, correction, or conversion. The new world which he helped to create was a growth rather than a structure. Silent men were observed about the country or discovered in the forest, digging, clearing, and building; and other silent men, men not seen, were sitting the in cold cloister, trying their eyes, and keeping their attention on the stretch, while they painfully deciphered and copied and re-copied the manuscripts which they had saved. There was no one that ‘contended or cried out,’ or drew attention to what was going on; but by degrees the woody swamp came a hermitage, a religious house, a farm, an abbey, a village, a seminary, a school of learning, and a city. Roads and bridges connected it with other abbeys and cities, which had similarly grown up, and what the haughty Alaric or fierce Attila had broken to pieces, these patient meditative men had brought together and made to live again.

Quoted by Joshua Brumfield, “The Dorothy Option?” in Dorothy Day and the Church: Past, Present, and FutureConferencee).

The Social Order Can be Reconstructed Today in a New Age of Migration

Today we are in what might be called a new age of migration.

There are signs of darkness – violence, untruths, hatred of other groups. Sometimes the lives of Catholics are even shaped and influenced by politicians rather than from the heart of the Gospel and the wisdom of the Church. We see the dark side of globalization, a world-wide laissez-faire capitalism that destroys the environment and the lives of people and causes them to leave their homes. We see the lasting harmful effects of colonialism.

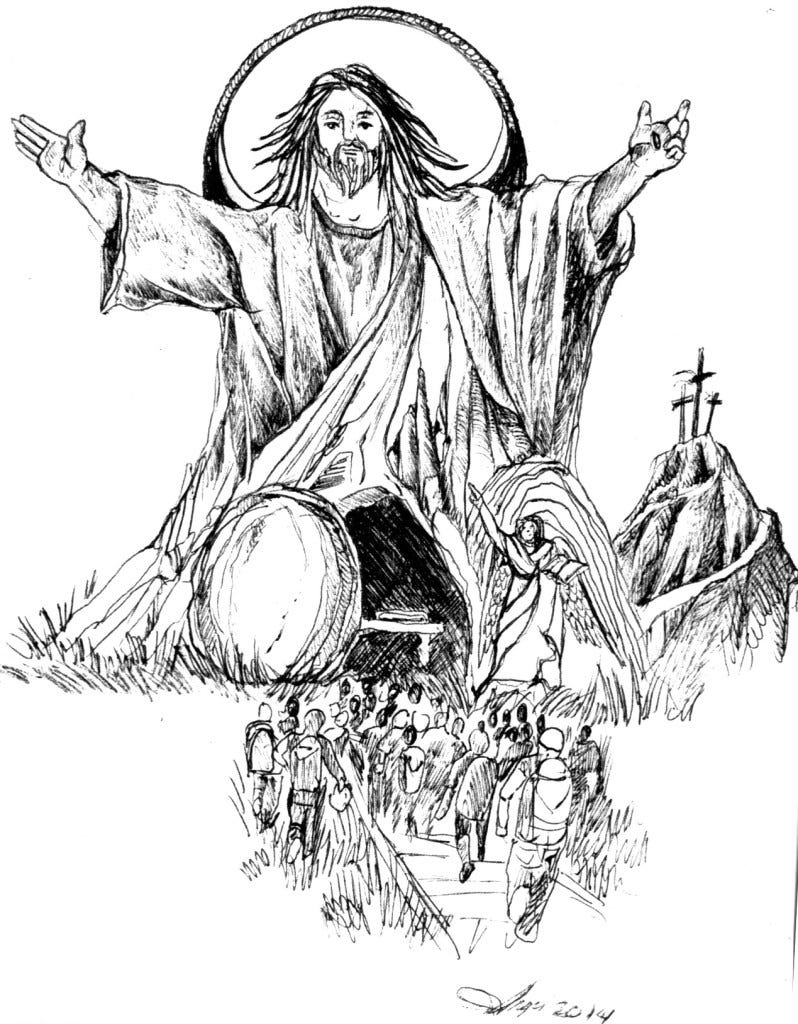

There is hope, however. With the Lord we can participate in the reconstruction of our world. Not through violence, insurrection, power seeking, but through the Works of Mercy, through support for small businesses and farms, support for workers, with hearts of flesh instead of hearts of stone. Not through what is being called Christian nationalism, but through the way of the Cross, through the Paschal Mystery, with Jesus the Christ to resurrection.

A renewal of the social order today will include the refugees and immigrants who have always been willing to do the hardest physical work, such as farm work and construction work and who are famous for creating small businesses. Some people think the refugees are not worth anything, but the people we meet here every day are people of a bright future in this country, if they are allowed to stay.

Parishes are receiving refugees at their Masses and are helping in many ways. Hopefully, more parishes will reach out, because refugees are often invisible in their communities.

Hope for Remaking our World is Through the Paschal Mystery and the Works of Mercy

Building the world according to the plan of the Living God will require giving of ourselves as the Lord did and working to change destructive systems that make it difficult for people to see God’s glory. As Pope Francis recently said,

On the Cross we will see His glory and that of the Father (John 12: 23, 28).

Jesus in the Gospel (cf. Jn 12:20-33) tells us something important: that on the Cross we will see His glory and that of the Father (cf. vv. 23, 28).

But how is it possible that the glory of God manifest itself right there, on the Cross? One would think it happened in the Resurrection, not on the Cross, which is a defeat, a failure. Instead, today, talking about His Passion, Jesus says: “The hour has come for the Son of man to be glorified” (v. 23). What does He mean?

He means that glory, for God, does not correspond to human success, fame and popularity; glory, for God, has nothing self-referential about it, it is not a grandiose manifestation of power to be followed by public applause. For God, glory is to love to the point of giving one’s life. Glorification, for Him, means giving Himself, making Himself accessible, offering His love. And this reached its culmination on the Cross, right there, where Jesus outspread God’s love to the maximum, fully revealing the face of mercy, giving us life and forgiving his crucifiers.

Pope Francis, Angelus, March 17 2024

The Catholic Worker Option

The Catholic Worker Movement provides an option for responding to the crises of our times. It offers a different way for us to live from what Pope Francis has called comfortable, consumerist isolation; a way that can take us beyond divisions to embrace the people of the world who are uprooted.

The Monastic Way, The Catholic Worker Way

The Catholic Worker movement began in the 1930’s during the Great Depression. When Peter Maurin presented his vision for the CW to Dorothy Day and to the world, he brought his studies of history to his teaching. He was also responding to the call of Pope Pius XI in his encyclical Quadragesimo Anno for Catholics to participate in reconstructing the social order. The Holy Father had made clear to all that neither Communism nor unfettered capitalism could address economic injustice:

Just as the unity of human society cannot be founded on an opposition of classes, so also the right ordering of economic life cannot be left to a free competition of forces. For from this source, as from a poisoned spring, have originated and spread all the errors of individualist economic teaching.

Quadragesimo Anno 88

Peter Maurin’s model had nothing to do with violent revolution, but was rather based on transforming the culture through the daily practice of the Works of Mercy.

Peter Maurin brought to the CW movement a model of the unity of manual labor and prayer and ideas. Some have said, “Why this sounds like monasticism.” There is some truth to this.

Peter presented the example of how the reconstruction of the social order was accomplished in the early centuries through the monasteries, centers of what he called cult (worship), culture, and cultivation (small farms) and encouraged parallels for the Catholic Worker movement to the work of the monks during that Age of Migration.

Both Peter and Dorothy read the Desert Fathers. He and Dorothy frequently pointed out that in setting up Houses of Hospitality and centers of thought in agricultural centers, the monks had brought light and learning to the people. Through voluntary poverty and personal charity they laid the foundations of the social order. Peter and Dorothy insisted that the method of the monks was a revolutionary technique, not the band-aid operation the Catholic Worker was sometimes accused of being.

As Joshua Brumfield wrote, “For Dorothy, Peter, and the early Catholic Worker Movement, making the [Fr. Hugo] Retreat, reciting prayers, and living a version of monastic life was all ordered towards loving God by loving neighbor, which meant changing the social order via the Works of Mercy.”

Dorothy Day wrote about the challenges involved in her book House of Hospitality:

The new social order as it could be and would be if all men loved God and loved their brothers because they are all sons of God! A land of peace and tranquility and joy in work and activity. It is heaven indeed that we are contemplating. Do you expect that we are going to be able to accomplish it here? We can accomplish much, of that I am certain. We can do much to change the face of the earth, in that I have hope and faith. But these pains and sufferings are the price we have to pay. Can we change men in a night or a day? Can we give them as much as three months or even a year? A child is forming in the mother’s womb for nine long months, and it seems so long. But to make a man in the time of our present disorder with all the world convulsed with hatred and strife and selfishness, that is a lifetime’s work, and then too often it is not accomplished.

Even the best of human love is filled with self-seeking. To work to increase our love for God and for our fellow man (and the two must go hand in hand), this is a lifetime job. We are never going to be finished.

Love and ever more love is the only solution to every problem that comes up. If we love each other enough, we will bear with each other’s faults and burdens. If we love enough, we are going to light that fire in the hearts of others. And it is love that will burn out the sins and hatreds that sadden us. It is love that will make us want to do great things for each other. No sacrifice and no suffering will then seem too much.

Reference and Recommended Reading:

Joshua Brumfield, “The Dorothy Option? Dorothy, Benedict, and the Future of the Church” in Dorothy Day and the Church: Past, Present and Future: Conference held at the University of Saint Francis, Fort Wayne Indiana. 2015.

Dorothy Day, House of Hospitality. Sheed and Ward, 1939.

Matthew Desmond, Poverty, By America. Crown Publishing Group, 2023.

Benedict Fitzpatrick, Ireland and the Foundations of Europe. Funk & Wagnalls, 1927.

Peter Maurin, Easy Essays. Wipf & Stock Publishers.

Pontifical Council for the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant People. Erga Migrantes Caritas Christi: The Love of Christ Toward Migrants. 2004.

Pope Pius XI, Quadragesmio Anno. Encyclical.

Leila Simona Tilani, “Migration and the ‘Dark Side’ of Globalization” European Politics and Policy Blogs. 2022.

Andrew L. Whitehead, American Idolatry: How Christian Nationalism Betrays the Gospel and Threatens the Church. Brazos Press, 2023.

Mark and Louise Zwick, The Catholic Worker Movement: Intellectual and Spiritual Origins, Paulist Press, 2005.

About us. Roundtable covers the Catholic Worker Movement. This week’s Roundtable was produced by Jerry Windley-Daoust and Renée Roden. Art by Monica Welch at DovetailInk. Roundtable is an independent publication not associated with the New York Catholic Worker or The Catholic Worker newspaper. Send inquiries to roundtable@catholicworker.org.

Subscription management. Add CW Reads, our long-read edition, by managing your subscription here. Need to unsubscribe? Use the link at the bottom of this email. Need to cancel your paid subscription? Find out how here. Gift subscriptions can be purchased here.

Paid subscriptions. Paid subscriptions are entirely optional; free subscribers receive all the benefits that paid subscribers receive. Paid subscriptions fund our work and cover operating expenses. If you find Substack’s prompts to upgrade to a paid subscription annoying, email roundtable@catholicworker.org and we will manually upgrade you to a comp subscription.