Is Christianity Compatible with Empire?

Mike Wisniewski issues a call to conversion. Plus: Remembering Gustavo Gutiérrez; CW letters from prison; and St. Francis CWers reflect on their time in the Catholic Worker.

The School of the Catholic Worker

This week’s issue features stories and reflections from four Catholic Workers who were part of the St. Francis Catholic Worker community in Chicago during different eras of its fifty-year history. Over the course of ninety minutes at the CW National Gathering earlier this month, they shared memories, funny stories, and insights. Their words often drew knowing laughter or nods of appreciation from those in the audience.

One of the most striking things about their testimony was how deeply their time at the Catholic Worker shaped the rest of their lives. It made me reflect on how my own two-year stint as a live-in volunteer at the Winona Catholic Worker profoundly shaped who I am today, in more ways that I can possibly enumerate here.

Above all, though, it taught me that a life lived for others, even when it takes you out of your comfort zone (sometimes way out of your comfort zone), is a joyful life, and the only life worth living. I was raised Catholic, so by the time I moved into the house, I had sat through at least 800 Masses, not to mention countless hours of faith formation. But the core truths of the Gospel can never really be “known” deep down in your bones until you actually step out and try them out for yourself.

A life lived in this way is not always easy or pleasant, as the St. Francis Catholic Workers readily attest. But it was remarkable how much love, laughter, and joy marked their testimony as well.

Jerry

Reader Letter: Remembering Michael Sprong

Felton Davis sent us this memory of Michael Sprong, who passed away October 16:

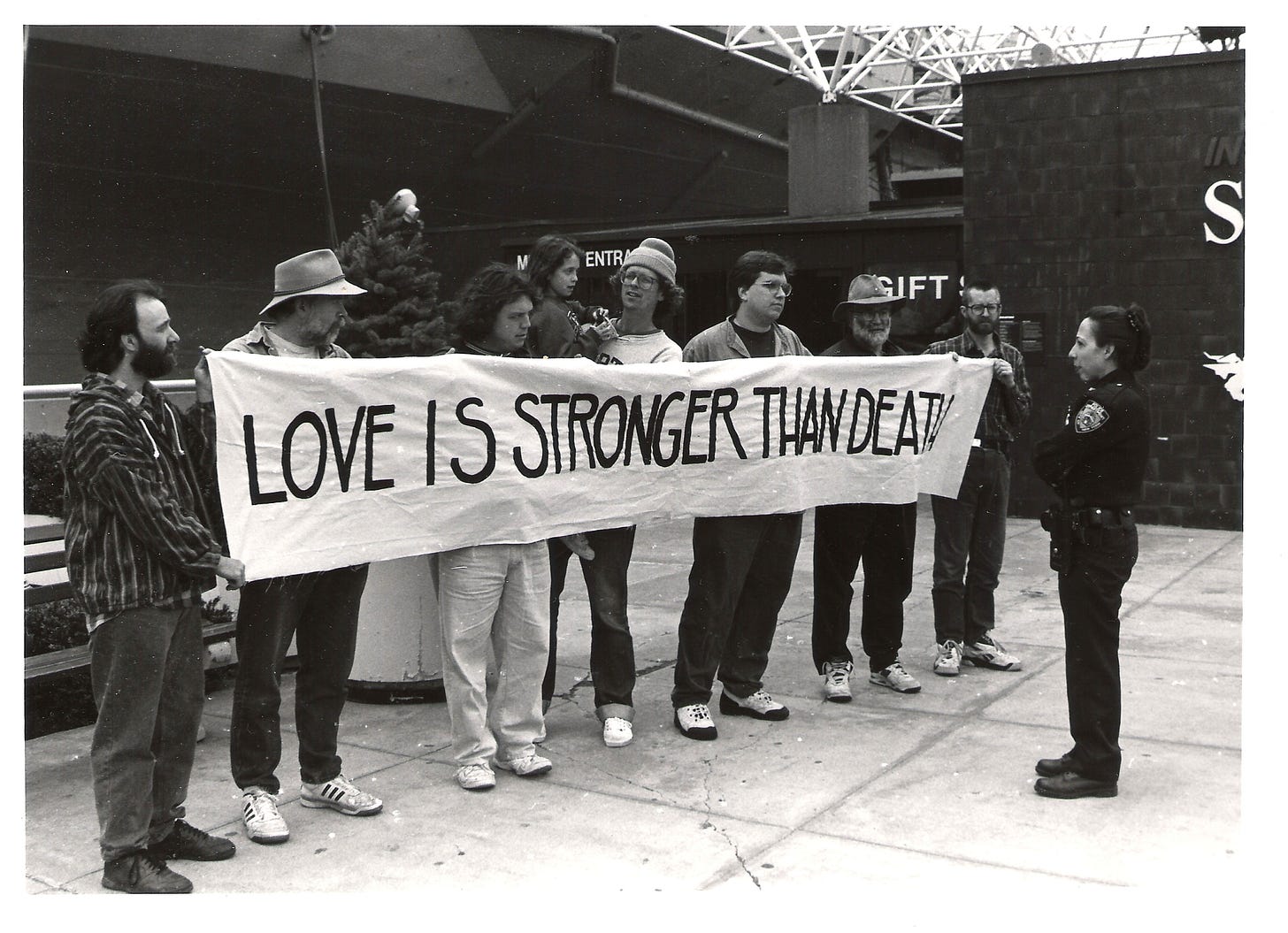

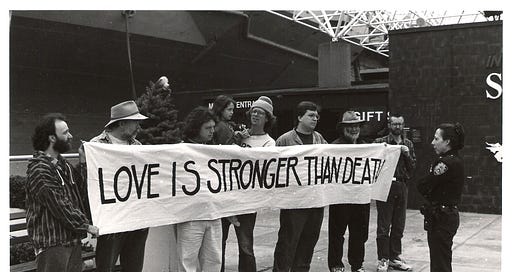

Seven of us were arrested at the Intrepid Museum on May 4, 1996, while the 75th birthday party for Fr. Dan Berrigan was getting underway. Patrick's 8-year old daughter Bernadette wanted to stay for the arrest, but the police officer threatened her with juvenile detention. Patrick put her down and told her no, not this time. Michael and I started work on the second edition of "The Nightmare of God," with Mary Lathrop dictating the chapters to me page by page. It was hard to get the punctuation correct because Mary would not say whether it was a comma, a semi-colon, a colon, or a parenthesis. And we standardized the Bible references, because Dan would write "(2, 4)" and leave it at that. That doesn't mean anything to most readers, so we substituted "Isa. 2:4" and similarly throughout. How many typos were in the Sunburst edition? I have no idea, and Fr Dan did not check our work at all. He just flipped through it and said "It looks good." Frank was not happy that we had to sit in the Midtown North Precinct for several hours, and he told me, "I have to be at the dinner, I'm locked in to that event." I told him, "The only place you're locked in is here at the police station." He arrived late but when he showed Dan the desk appearance ticket Dan was amazed. Had we told him about the action he might have skipped the dinner in favor of coming to the Intrepid with us. --Felton

If you missed last week’s issue, you can read more about Sprong’s remarkable life here.

FEATURED

Christianity and Empire: A Call to Conversion

In last week’s issue, we ran an excerpt from the October issue of the Los Angeles Catholic Worker’s newspaper, the Catholic Agitator, in which Matt Harper weighed the question of whether Catholic Workers ought to vote in the upcoming election, given the Catholic Worker’s history of eschewing partisan politics. This week, we consider the broader context for that question with a little help from Agitator co-editor Mike Wisniewski.

“As I write, the Democratic National Convention is at its height with a delirium reminiscent of the 2008 and 2012 DNC when Obama (the savior) was the candidate,” Wisniewski writes in an essay that also appeared in the Agitator’s October issue. “Now Harris is being hailed as yet another ‘savior,’ who will ‘save democracy.’”

This is absurd, Wisniewski says, because the situation in the United States more closely resembles empire than democracy. Moreover, for Christians, Jesus is the only legitimate savior. Authentic Christian faith is inherently revolutionary, he says, and incompatible with supporting imperial power.

Here’s an excerpt:

The Christian faith is revolutionary. Again, the Christian faith is REVOLUTIONARY. Dwell on this for a moment and grasp its significance. Allow it to permeate your entire psyche. As Christians, we are a holy people, a people set apart, different from the masses, a people whose foundation, whose essence, is love, nonviolence, and truth.

Therefore, we are a people who view matters differently, from a spiritual perspective (attentive to the unseen powers—both good and evil). A perspective of nonviolence and what is just, equitable, and serves the common good. A perspective that upholds the dignity and sacredness of human life, and human rights. A perspective that unites us with each other and the rest of YHWH’s “good” creation.

Accordingly, our presence in the world must be distinctive, prophetic, and profound. We are called by name to make a difference, become adherents and exemplars of gospel principles who tirelessly labor to further God’s nonviolent Kin-dom initiated by Jesus Christ, the One we are called to listen to, follow, and emulate. There can be no duplicity.

With more than two billion followers, the Christian faith is the largest religion on the planet. With approximately 210 million followers, Christianity is the largest body of believers in the U.S. This implies that we, individually and collectively as church, the Mystical Body of Christ, possess the power, and mandate, to effectuate authentic change. Set a new agenda. Create a nonviolent alternative reality from the abominable status quo. Standing in nonviolent resistance to and in non-cooperation with immoral and unjust capitalism, and tyrannical and heartless imperialism. Indeed, anything that is contrary to and in opposition with Jesus, and his message. And, as Peter Maurin, Catholic Worker movement co-founder, articulated, “Create a new society in the shell of the old…a society where it easier for people to be good.”

Our faith teaches that we belong to and therefore must love YHWH above all things, worshipping and serving YHWH alone, and being attentive to both, the spiritual (see Ephesians 6:10-12), and mortal aspects of our faith. We aspire to please YHWH at all times. In return, the Spirit opens our eyes and hearts to know the truth, then leads us forward in love with true freedom. We become God’s co-workers.

Scripture makes it unambiguously clear that it is impossible to simultaneously serve two masters—God and empire (see Luke 16:13; Deut. 6:13; Exodus 23:24-25a). We allow one or the other opposing principles to become our fundamental inspiration, our creed. Therefore, as people of faith, we cannot participate in, support, promote, collaborate with, or uphold anything contrary to gospel principles, contrary to YHWH’s purpose; contrary to the love of God, self, neighbor, and enemy. Our thoughts, words, and actions, must always bless and glorify YHWH, who desires loyalty above all else.

To accomplish this, YHWH freely offers us grace, wisdom, and guidance to understand and achieve what is right and just in God’s eyes. To live in the light of gospel truth, not in the darkness of imperial deceitfulness and violence. This means we act as YHWH’s adopted children, and Christ Jesus’ ambassadors, not as empire’s minions and advocates. Therefore, it is to Jesus Christ alone to whom we pledge our allegiance, dedicating our life to the common good, with the poor and victims of injustice paramount.

Understanding this, we have to wonder: How did we get to this scandalous and crazed place where most Christians willingly, and often enthusiastically, support what is contrary to gospel principles? Specifically, supporting and participating in this corrupt, immoral, unjust, and evil system—at all levels, including voting and holding political office, serving in the military, and law enforcement. All of these serve empire’s purposes. Hence, we become captives of empire. Rather, in the Letter of James (1:22, 27b) we are presented with this sound advice: “Be doers of the word and not hearers only, deluding yourselves…keep oneself unstained by empire.”

You can read the rest of his essay at CatholicWorker.org: Christianity and Empire: A Call to Conversion.

Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez Remembered as Father of Liberation Theology

Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez O.P., widely known as the “father of liberation theology,” passed away at his apartment in Lima, Peru, on October 22 from complications of pneumonia. He was 96.

Gutiérrez’s work as a parish priest in the slums of the Rimac neighborhood of Lima, along with his exposure to leading theologians of the 1960s such as Marie-Dominique Chenu and Yves Congar, eventually led to the publication of his groundbreaking book, A Theology of Liberation. Published in Spanish in 1971 and in English in 1973, the book spawned a wider movement of the same name. At the heart of his work, he said, was the question: “How do you tell the poor, ‘God loves you?’” Gutiérrez challenged the notion that God’s work of salvation is purely spiritual; instead, the same God who liberated the Israelites from slavery in Egypt also desires to save the poor from the evil of poverty and violence here and now. If this is God’s will, he said, then Christians must practice a “preferential option for the poor,” standing in solidarity with the poor and marginalized as they cooperate with God to work for liberation from structures of sin.

Liberation theology profoundly affected the entire Church, as evidenced by the standing ovation Gutiérrez received at a 2014 event at the Vatican, and its ideas were picked up by numerous Catholic Workers. Gutiérrez was a professor emeritus of theology at Notre Dame until 2018, although it wasn’t clear at the time of this writing whether he ever connected with the South Bend Catholic Worker.

He did, however, visit the New York Catholic Worker in the fall of 1976; his visit was recounted by Daniel Mauk in the December issue of The Catholic Worker:

Two other distinguished visitors were Frs. Sergio Torres and Gustavo Gutierrez, Latin American priests, who spoke on the developing theology of liberation, particularly its attitude toward violence and nonviolence. Liberation theology tends to take a pragmatic view of the issue of means, and both men confessed that it is usually conservative groups that show such concern for the question of revolutionary violence; the same groups demonstrating such insensitivity to the violence inherent in certain economic systems. Fr. Gustavo remarked how unusual it was in his experience to encounter people whose disagreement with violent means was as strong as their opposition to oppression. Many perplexing questions and thoughts were raised that evening, but what impressed me the most was the humility and desire to learn together with us of these two men, so committed to the liberation of the oppressed.

According to an article released by the University of Notre Dame, when he was asked late in life how he would like his work to be remembered, Gutiérrez responded, “I hope my life in the end tries to give testimony to the message of the Gospel: Above all, that God loves all people, especially those that the world considers most insignificant.”

You can read an in-depth account of his life and theology at America magazine.

St. Francis CWers Reflect on Lessons Learned from 50 Years of Community

“Lessons Learned from 50 Years of St. Francis House” was the title of a panel at the National Catholic Worker Gathering in Chicago on October 5th. Panelists from different eras of the St. Francis House Catholic Worker community shared stories and reflections, providing insights into the daily work of hospitality and what enables a Catholic Worker community to thrive for fifty years.

The panel featured Lucky Marlovitz, who lived and worked at the house from 2000 to 2011; Ruthie Woodring, a resident from 1993 to 2002; Sam Guardino, a member of the live-in community from 1990 to 1993; and Denise Plunkett, who served from 1978 to 1982. Their stories ranged from humorous memories to hard-won lessons. Karl Meyer also participated in the panel; he read written comments that will be posted in their entirety in the coming weeks.

In the meantime, here are some of the stories they shared:

Lucky Marlovitz: Learning to Say ‘Sorry’ and ‘No’

Lucky Marlovitz lived at the house from 2000 to 2011. Prior to encountering the Catholic Worker, she had been doing forest defense in Northern California. Although she had been raised Catholic in Chicago, she had never heard of the Catholic Worker Movement—until she encountered one of the St. Francis Catholic Workers, Jack Trumkey, behind a health food store in the early 1990s.

“I went to the back of a health food store, and there was this guy, like all scientific, dressed up in a button-down shirt, aviator glasses, had everything all organized. And that’s how I learned about the Catholic Worker movement.

“So yeah, Jack, well, he lent me a rope to tie these organic carrots onto my back and ride away with it. And I said, ‘I want to return this rope.’ And he said, ‘I live at St. Francis House Catholic Worker.’ That’s how I found out about it.”

The plenary panel was titled, “Lessons Learned from Living at the St. Francis Catholic Worker,” and she listed quite a few.

“Things I learned at the house: I learned how to say ‘no.’ As a woman, you’re supposed to be able to do everything all the time. So, I did learn how to say ‘no.’

“I learned how to say ‘sorry.’ I effed up majorly, like a lot of times in my years there. And it took a while sometimes, and I know it affected people in different ways. I learned how to say sorry to people, to take accountability for my actions, as much as I can.

“Giving thanks: I was thankful for the experience of living there, of the education. I lived with over 400 people. I did have to go and count once because I did a testimony for the State of Illinois, and I looked at the registry. I lived with over 400 people in that time. So I had experience with people from all over the world, with many people.

“I learned that I could live with many people, dozens of people, hundreds of people. But I really only liked to live with a few.” This line drew knowing laughter from the other Catholic Workers in the audience.

“I learned it was good to take breaks…. I know Dorothy Day would go do nonviolence, civil disobedience, and go to jail to have a break. I would go to Southeast Asia. A little different, right?”

Ruthie Woodring: ‘I Hadn’t Seen Violence Until That Night’

Ruthie Woodring was at the house from 1993 to 2002. She began by showing off her 50th-anniversary shirt and explaining that since she was born in 1974 and she is a trash hauler, she has been “looking out for fiftieth-anniversary things.”

She grew up Christian in Appalachia but lost her religion at age 17. She left college at age 19 to move into St. Francis House—in part to go somewhere where people weren’t constantly worried about the state of her soul and whether she was saved.

One of her first “lessons learned” came while she and another worker were leafleting at the University of Illinois about getting Amoco to divest from Burma. She followed that worker into one of the buildings.

“So he steps in this door, I step in right behind him. The whole door thing moves, it hits me in the back. It sort of jams me into the frame. And he’s like, ‘Ruthie, what are you doing?’ I’m like, ‘I’ve never been in a revolving door before. Like, how do you get in this thing?’”

Woodring came to St. Francis House as a non-Christian from a family of teetotalers. At the time, the house had 18 residents and maintained an open-door policy from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. She recalls one cold winter day, returning from her bike messenger job to find 30 people gathered in the living room, with additional people in the basement.

“It was kind of a lot. And then people would be sometimes hanging out in the basement, smoking crack in the basement. And I mentioned the teetotaler thing, because we had a policy that you had to be sober to come inside the house. And so when I would open the door, and someone would want to come in, I’m like, I don’t know if they’re sober or not. And Terry Bacman—from St. Louis, Missouri, home of Anhauser-Busch—he’s like, where’d you come from that you can’t smell alcohol on someone’s breath? Like, where are you from?”

“I also learned what crack smells like. You know, you always mix it up with poop. Like, I can never quite distinguish the smell between bleach and poop, or crack smells and poop, or something worse.

“So we decided that…having an open door from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. was just too chaotic of a household for the other 18 people who lived there. So we decided to kind of not be the drop-in center anymore, and just try to focus on creating a healthy, supportive home for those people who, it was their home. Seven, Love, Jimmy, Jack, those four long-term guests were there when I moved in, too.

“Like Lucky was saying, how she got to live with people from all over the world, I’m also thinking about people that lived with us from the Center for Survivors of Torture in Uptown. So I heard firsthand stories of people’s experiences in Guatemala and Uganda and other places—speaking of perspective.”

One of her “lowest moments” at the house happened when she called the police to help with a guest. The house was facing gentrification pressures, with neighbors complaining about people using their porch, sometimes for drinking or drug use. These neighbors would frequently call the police or health inspectors.

“We had a policy against calling the police,” she explained. “I came home at midnight and there was a guy sleeping on the porch, and I was concerned about neighbor relations, and everyone else was asleep.” She tried to wake him up, but when she wasn’t successful, she called the police.

“Denise said she had never seen violence at the house, and I hadn’t either, until that night,” she said. “I thought the police would just tell the guy to leave, but they came, they dragged him off the porch, they punched him, kicked him, threw him against the neighbors’ fence and stuffed him in the police car and drove away with him.”

The next day, she attended a meeting with police at the precinct and another in their kitchen. “That was a learning moment that I am not proud of.”

Sam Guardino: Personal Responsibility, Boundaries Helped Keep Community Going

Sam Guardino first came to St. Francis House in 1981 and was a member of the live-in community from 1990 to 1993. “And I wasn’t burnt out when I left; I was just in love before I had burnout. Those things happen.”

Guardino emphasized the importance of “blurriness” in the Catholic Worker community: while boundaries existed, they weren’t as rigid as in conventional society. The roles of workers, guests, and visitors were fluid, with guests sometimes becoming workers and visitors becoming guests. However, there was always a core group of people willing to take responsibility when needed, which helped the house reach its 50th anniversary.

“I want to focus on one reason St. Francis House is having a 50th birthday: because people were willing to take responsibility over the years in times when things needed to be done,” Guardino said. “Sometimes that meant doing an emergency dumpster dive for food.”

Another important example of an individual taking personal responsibility for doing something hard that needed to be done came when the community was facing pressure from the neighborhood, which was undergoing gentrification in the 1980s. The house was frequently visited by city housing inspectors who would cite it for violating the city building code. Fortunately, the community had a lawyer living in the house, Mark Miller, who took responsibility for going to the hearings.

“By the way…we never set a number about how many people lived in the house. It was kind of that variable, ‘N.’ Right? And then, of course, we had Donald James Delano at the front door letting anybody in. He would’ve let a SWAT team in—in a very remarkably loving way.”

Earlier, Lucky had mentioned that she probably would not have wound up at the Catholic Worker if it hadn’t been listed as a secular community in a directory she was looking at. Guardino elaborated on the tensions between the religious and the secular at the house with a story about a French priest.

At the time he was living in the community, they had Mass on Thursdays, inviting different priests who were supportive of the community to come celebrate. While the community believed in receiving communion under both species, they insisted on using grape juice rather than wine out of respect for those members of the community struggling with an addiction to alcohol.

Once, the community invited a French worker-priest named Benoit Charlemagne to say Mass. Even though he had lived in Uptown since the 1970s, his English was poor.

“Trying to explain to Benoit Charlemagne, who had very little English…and who was a Frenchman, a true-to-the-heart Frenchman, that we were going to have grape juice and not wine—it took a long time to explain it to him.

“And then during the liturgy…Benoit goes in, ‘Jesus took the bread and the grapefruit, and shared it with his friends…’ It kind of maybe sums up this secular creativity that was going on at the house.”

Denise Plunkett: ‘The Luckiest Offer of a Lifetime’

Denise Plunkett was at the house from 1978 to 1982. “I looked into the Worker when Chris Perry left. She asked me if I would be interested, when she left, moving in, and about a year later, she left. So, I felt like it was the luckiest offer in my life. It was an amazing experience.”

A number of other Workers arrived shortly after she did: Lynn Rothmiller, along with Henry Nicolella and Mike Sullivan, both of whom had previous Catholic Worker experience in New York. A significant addition to the community was Joan McKinley, a nun from St. Louis, who, although living in her own apartment nearby, volunteered at the house daily from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., providing a consistent presence while others were at work. Roy Bourgeois, a Maryknoll priest, also moved into the house.

“We had very easygoing staff living there. I don’t ever remember a fight in the house or anything. I don’t remember an unpleasant moment, really. And we had visitors constantly, because it was fun.”

Fr. Bill O'Brien, a young Jesuit who had lived at the Catholic Worker, was organizing the Jesuit Volunteer Corps and housed Jesuit volunteers in two six-flat buildings a block away.

“So some of them would come over every night. Kristen and Sarah would come and play guitar and get everybody singing, so the people in the house knew all these young folks in the neighborhood. Everybody loved everybody and counted on everybody.”

Read a longer version of this article at CatholicWorker.org to hear about how Plunkett met Seven; Guardino’s insights about the importance of maintaining healthy boundaries, nonviolently; and Woodring’s account of the time the community protested Chicago ordinance 880a with a topless bike ride past the Museum of Modern Art: Lessons Learned from 50 Years at St. Francis Catholic Worker.

THE ROUNDUP

Reznicek Will File Clemency Appeal; Raises Money for Fellow Inmates. Jessica Reznicek will apply for clemency from the U.S. president after the upcoming election, regardless of who wins, says Frank Cordaro of the Des Moines Catholic Worker. Reznicek was recently released from disciplinary lockdown and cleared of any involvement in an altercation in her unit, he said. During her time in solitary confinement, Reznicek still managed to coordinate a donation of $600 to support the family of a fellow inmate in need, continuing her efforts to assist others in her “prison family.” Those wishing to donate to Jessica Reznicek’s Prison Fund can send checks made out to "The Des Moines Catholic Worker," with "Jess's Prison Fund" noted in the memo. Donations can be mailed to: Des Moines Catholic Worker, P.O. Box 4551, Des Moines, IA 50305.

A Prison Letter from Susan Crane. “While I’m in the prison, I feel wrapped in the kindness, generosity and community of the women in prison with me, and the kindness of guards,” writes Susan Crane of the Redwood Catholic Worker in a letter from the German prison where she is serving a 229-day sentence for her nonviolent actions protesting tactical nuclear weapons at Buchel Air Base. “And while I’m out in the church and the community, I feel wrapped in kindness and compassion, and a generosity of spirit that continues to humble me…. When I’m in prayer, I feel wrapped in God’s love, and at the same time knowing that God’s love includes all those in prison, all those under the bombs and running for their lives, and all those who are caught in the powers and principalities who participate in war and oppression.” Read the rest of her letter at Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action.

The Journey to Passing a Climate Emergency Resolution. In this fourth installment of his journey into climate activism, Anthony Lanzillo of Duluth's Bread and Roses Catholic Worker describes how a Chicago training session catalyzed his involvement with the local Climate Mobilization Campaign. Despite initial resistance from city council members who viewed Duluth as a "climate haven," their persistent grassroots campaign succeeded in passing a climate emergency resolution and establishing new environmental initiatives. See how he did it at CatholicWorker.org: The Path to Passing a Climate Emergency Resolution in Duluth.

Dorothy Day and the Saintly Six: A Webinar on Black Catholic Saints and Political Engagement. On Thursday, November 14 (7 p.m. Eastern), join the Dorothy Day Guild for an enlightening discussion exploring the intersection of Dorothy Day's legacy with the six Black American Catholics currently under consideration for canonization. The panelists will examine how these remarkable figures provide a model for politically engaged holiness in contemporary times. Panelists include Dr. Kim Harris, Deacon Mel Tardy, Joanne Kennedy, and Dr. Andrew Prevot, with Dorothy Day Guild Co-chair Dr. Kevin Ahern moderating. Register here for Zoom link.

Dorothy Day: Practices of Peace in the Year of Jubilee. Date: Saturday, March 29th, 2025 | Format: In-person and virtual options | Location: Dorothy Day Center at Manhattan University. The Dorothy Day Guild is sponsoring an academic symposium exploring Dorothy Day's legacy and its significance in the 21st century. The Guild is calling for proposals (300-500 words) from scholars at all levels and peace practitioners whose work reflects Day's commitment to hospitality, Gospel nonviolence, and voluntary poverty. Students and Catholic Worker movement members are especially encouraged to submit proposals for papers, panels, and creative presentations. Proposal deadline: January 1st, 2025. Read the call for papers here.

A FEW GOOD WORDS

“What do the Simple Folk Do?” by Dorothy Day

This editorial first appeared in The Catholic Worker in the May 1978 edition. Dorothy Day originally created this talk for a symposium on transcendence ten years before. you can read the full editorial on catholicworker.org.

God made men and women to be happy. When I visited Cuba in 1962, that was the appealing slogan which I read on the billboards: “Children are born to be happy.” Yet, how can we be happy today? How can we believe in a Transcendent God when the Immanent God seems so powerless within time, when demonic forces seem to be let loose? Certainly our God is a hidden God.

Men and women have persisted in their hope for happiness. They have hoped against hope though all the evidence seemed to point to the fact that human nature could not be changed. Always they have tried to recover the lost Eden, and the history of our own country shows attempts to found communities, where people could live together in that happiness which God seemed to have planned for us. Charles Dickens writes about one such community on the Mississippi in Martin Chuzzlewitt, and Dostoyevsky refers to a community in Illinois where two of the characters in The Possessed had gone to look for earthly happiness. Most of these references to community poke fun at the attempt, and Edmund Wilson’s history of community in To The Finland Station is certainly not sympathetic. Martin Buber in his Paths in Utopia was the only modern writer who held out hope for a modern, voluntary community as a place where men and women could live in love and in the happiness which God intended for them.

St. Teresa said that you can only show your love for God by your love for your neighbor, for your brother and sister. Francois Mauriac, the novelist, and Jacques Maritain, the philosopher, said that when you were working for truth and justice you were working for Christ, even though you denied Him.

But how to love? That is the question.

All men are brothers, yes, but how to love your brother or sister when they are sunk in ugliness, foulness and degradation, so that all the senses are affronted? How to love when the adversary shows a face to you of implacable hatred, or just cold loathing?

The very fact that we put ourselves in these situations, I think, attests to our desire to love God and our neighbor. Searching for transcendence in community has resulted in the Catholic Worker houses of hospitality and our so-called farming communes. Actually, Peter Maurin, the founder of the Catholic Worker and a French peasant, liked to call them agronomic universities, and there have been many attempts throughout the country to get these small centers under way, most of them resulting in failure as far as one could judge. But no one who ever lived in one of them ever forgets this “golden period” of his or her life. It has always required an overwhelming act of faith. I believe because I wish to believe, “help Thou my unbelief.” I love because I want to love, the deepest desire of my heart is for love, for union, for communion, for community.

How to keep such desires, such dreams?

Certainly, like Elias, who, after making valiant attempts to do what he considered the will of God, fled in fear, all courage drained from him, and lay down under a juniper tree and cried to God to make an end of his misery and despair.

The grace of hope, this consciousness that there is in every person, that which is of God, comes and goes, in a rhythm like that of the sea. The Spirit blows where it listeth, and we travel through deserts and much darkness and doubt. We can only make that act of faith, “Lord I believe, because I want to believe.” We must remember that faith, like love, is an act of the will, an act of preference. God speaks, He answers these cries in the darkness as He always did. He is incarnate today in the poor, in the bread we break together. We know Him and each other in the breaking of bread.

Roundtable covers the Catholic Worker Movement. This week’s Roundtable was produced by Jerry Windley-Daoust and Renée Roden. Art by Monica Welch at DovetailInk.

Roundtable is an independent publication not associated with the New York Catholic Worker or The Catholic Worker newspaper. Send inquiries to roundtable@catholicworker.org.

China and Russia are much more imperial powers than this country. And simply not voting is irresponsible- handing the election to the winner even though he/she may be much worse than their opponent, even though neither are good. So let’s take a global view and not just beat up on this country.