Living Toward a 'Marvelous Victory': Scenes from a Catholic Worker Life

At the CW National Gathering, longtime Catholic Worker Michael Bremmer shared stories from forty years doing the works of mercy with many friends, living toward Howard Zinn's 'marvelous victory.'

You’re reading CW Reads, the Thursday edition of the Catholic Worker Roundtable. For our inaugural issue, we’re bringing you the speaking notes from Michael Bremmer’s address to the Catholic Worker National Gathering in Chicago this past October.

Michael Bremmer’s journey with the Catholic Worker movement began on the lumpy couches of Chicago’s St. Francis Catholic Worker House in the 1980s, when Michael was in his early 20s. He’d come to an advertised “round table discussion” expecting to find an actual round table; instead, he found lumpy couches and a very confusing (to him, at the time) Oblate priest named Fr. Karl Kabat.

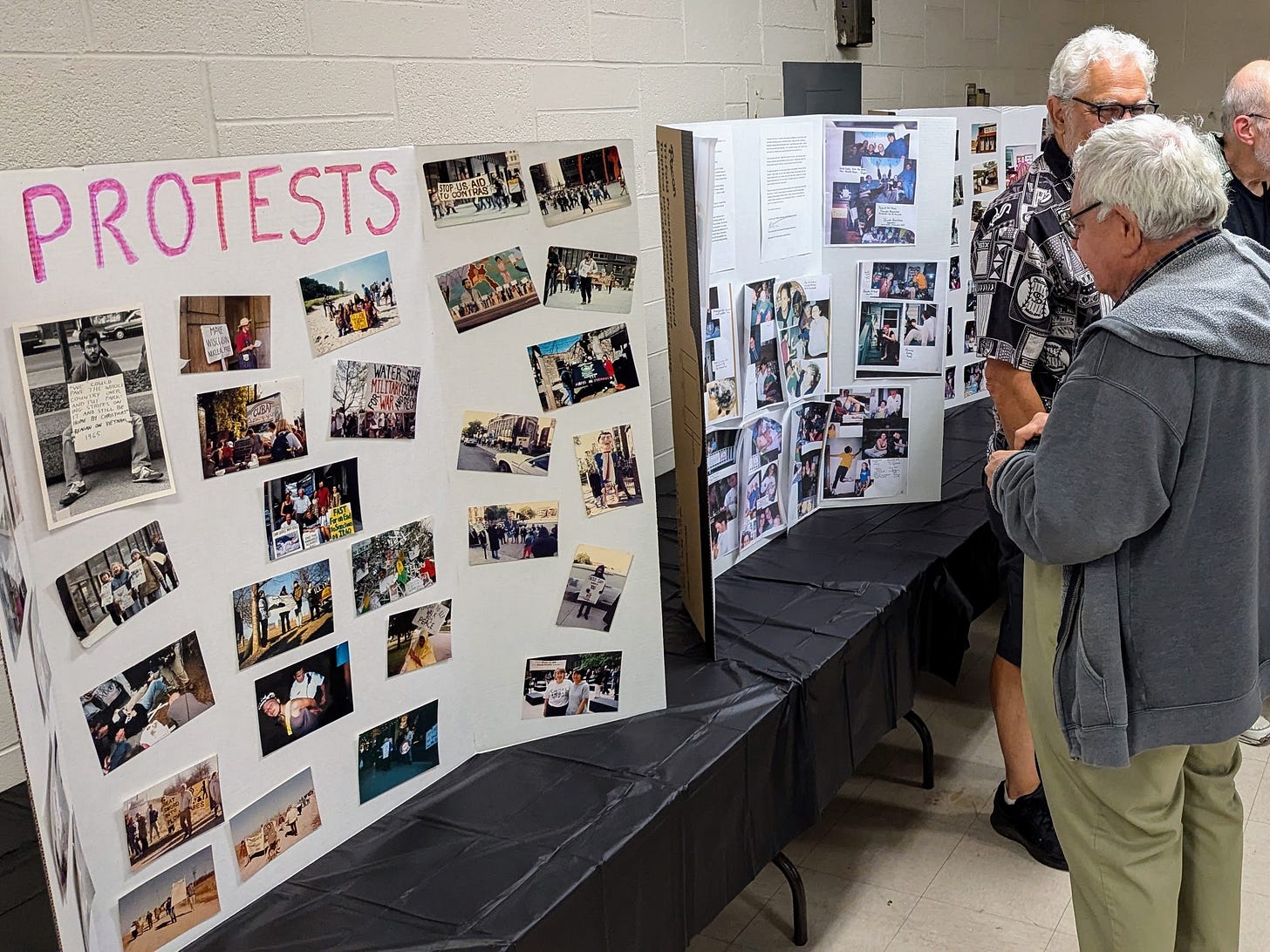

That shaky introduction to the Catholic Worker eventually led Bremmer to a lifelong involvement in the Catholic Worker, as well as various peace and justice initiatives. In this deeply personal account, Bremmer weaves together stories from his time at St. Francis Catholic Worker House in Chicago's Uptown neighborhood, his activism against nuclear weapons and war, and his encounters with an eccentric (but lovable) cast of characters who made the house their home, from a dumpster-diving PhD to a Jewish woman named Love who loved to sing Christian hymns…in the third person. He also shares stories about challenging the nuclear war infrastructure in northern Wisconsin, the devastating U.S. sanctions in Iraq, and the heartbreaking effects of U.S. intervention in Central America.

Michael generously provided the notes from his talk, which follow. His talk departed from these notes in places; if you’d like to get a flavor for it, there’s a link to an audio recording at the end of this piece.

Michael Bremmer’s Forty-Year Adventure in the Catholic Worker

Michael Bremmer’s address at the Catholic Worker National Conference, Chicago, October 4, 2024.

The first time I set foot in St. Francis Catholic Worker House was sometime in the early 1980s. It was a Sunday night roundtable discussion that featured an Oblate priest who had been part of the Plowshares 8 action at a nuclear bomb facility at King of Prussia, Pennsylvania. When I got to the house, I expected to find a literal round table like you see in those Fritz Eichenberg ink prints. Instead, I found rows of lumpy old couches, and I took a seat.

Fr. Karl Kabat talked about the civil disobedience action of spilling blood on Mark IV missile coneheads and how he and his co-defendants were facing long prison sentences. He talked about the relevance of the prophet Isaiah's message of "beating swords into plowshares" in the modern age of nuclear weapons. At the end of his talk, Fr. Karl began to talk about abolishing the prison system. This seemed to my overly logical 22-year-old mind to be at odds with the strategy of civil disobedience. Where were they going to put you for breaking the law—however unjust—if all the prisons were abolished?!

Milwaukee and Early Activism

Between 1983 and 1985, I lived in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and visited Casa Maria a few times. I got to know Don Timmerman, and he introduced me to war tax resistance. We handed out the War Resister's League's pie chart leaflets with a dollar bill stapled to each one. If you're going to do this, realize the word will get out on the street very quickly, and your leaflets and dollar bills will be gone in no time.

That was fun. Not so much fun was going with Don to gun shops outside of Milwaukee to protest the sale of firearms that were claiming the lives of so many people in the inner city. The verbal assaults from the shop owners and patrons were unpleasant, to say the least.

Witness for Peace in Nicaragua

In 1986, I decided to join the Witness for Peace team for a year in Nicaragua. The US-funded contra war was raging, and I was convinced that more Americans living there might help stop another Vietnam. Witness for Peace had about 40 long-term volunteers spread out across areas of conflict throughout the countryside. We led and translated for delegations of people from the US, Canada, and Mexico who came to experience a little bit of what life was like for Nicaraguans living in a war zone. It was awe-inspiring to be part of this experiment in nonviolence. For the duration of that war, hundreds of people of conscience from across our continent came together in an effort to stop a terrorist campaign funded by the Reagan administration.

One story stays with me. I spent a day and night in a hospital in Juigalpa after a Contra attack on a village called La Santos. I met a 12-year-old girl named Ruth Maris whose leg had been fractured by machine gun fire. She was worried because neither of her parents had yet come to see her. We played cards and other games while we waited for someone from her family to show up. Finally, in the morning, a man stood in the doorway, and I was relieved to know it was her father. I stepped out of the room as the two embraced and then caught the eye of a nurse standing nearby. "¿Y su mamá?" ("And her mom?"), I asked her. She shook her head and whispered "no." Think now of children today in Gaza, Sudan, Ukraine...

When I got back, well-meaning friends and family members would ask me if I had adjusted to being back in the US. I didn't know how to respond honestly. My friend Virginia Druhe, who was on the Witness for Peace team and a longtime Catholic Worker from St. Louis, had an answer: "By God's grace, I may never adjust to being back." How did Dorothy Day say it? "Our problems stem from our acceptance of this filthy rotten system."

There was a group called Pledge of Resistance which met regularly to plan demonstrations and direct actions in Chicago. The chapter in Uptown was one of the most active, and where did they meet? Those lumpy couches at St. Francis Catholic Worker.

Over the next two years, I was arrested for nonviolent protest action more than a dozen times. Some people more than that, but who's counting? [Speaking to Karl Meyer in the audience] Karl, were you keeping track?

Nuclear Disarmament and Prison Time

In 1988, a group of us from Uptown began to make plans for a nuclear disarmament action headed up by a group of troublemakers from Wisconsin. I'm talking about people like Sam Day, Bonnie Urfer, Cassandra Dixon, Mike Miles, and John LaForge of Nukewatch and Anathoth Farm. They organized the Missouri Peace Planting—a sort of Plowshares action lite that involved occupying missile silo lids but not doing any jackhammering. The sentences would be lighter, and perhaps more people would come on board. "Jump in—the water is fine," as Sam Day liked to say.

In August 1988, fourteen peace activists, including Chicagoans Sam Guardino, Kathy Kelly, Katey Feit, and myself, entered ten different Minuteman II missile silos at the same time. The alarms went off at Whiteman Air Force base, and they sent SWAT teams in armored personnel vehicles out to greet us. So, I did end up at one of those prisons that good Father Karl had failed to abolish—Yankton Federal Prison Camp, which only a few years before was the campus of Yankton College. It was still equipped with tennis and bocce ball courts when I was there in 1989. When my mom came out to visit, she commented on how beautiful the grounds were and that the other prisoners she met in the visiting room were so polite and courteous. "What are they in prison for?"

"That's a good question, Mom."

My sister also drove out with her four children, and I realized she had never traveled further than 90 miles from Chicago. "Look what I have to go through to get you to leave the city!"

About six months after coming home from Yankton, Paul Kapczuk, who was living at St. Francis House at the time, asked me if I could come stay at the house to help out while he was visiting family in Cleveland. "Just a few weeks? Sure, why not." Is he here tonight? [Gestures to Paul Kapczuk] It's been a minute, Mr. Kapczuk!

Life Inside St. Francis House

The first thing about living at a Catholic Worker House was figuring out who are the workers and who are the guests. They can look an awful lot alike, especially the longer they have been there. And then you have long-term guests who have great influence on the culture of the house.

At this point, I want to say that any resemblance of the people and events I mention here to real people you think you recognize is purely coincidental. The food supply for the community was headed up by a man named... let's call him John. Okay, you all know I'm talking about—the master dumpster diver named Jack. Jack made dumpstering food into a science. In fact, he was a scientist with a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in botany. Jack knew the day and time certain food was likely to be thrown away at local grocery and health food stores. "3:00 pm on a Tuesday—better get over to Butera. They'll be throwing away dairy products." One time Jack got word that the freezer at Walgreens broke down and they were unloading the ice cream. Next thing you know, everyone is walking around the house with their own pint of Ben & Jerry's: "What flavor you got?" "Chunky Monkey. How 'bout you?"

Our loyal doorman for three decades was named Donald James, aka "Jimmy." Donald came with the house back in 1974 as he had been a guest of the previous community. He sat by the front door and welcomed in everyone, unlocking the door for homeless people coming in off the streets, of course, but also housing inspectors, police detectives... and famously on one occasion, FBI agents who came to arrest Plowshares activist Jerry Ebner, who was napping on a couch of all places.

Then there was this older woman who lived at the house and went by the name of Blythe Spirit or sometimes Hilliard Hodgekiss but mostly was known as— [gestures to the audience to respond; people shout:] "LOVE!"

Yes. For the better part of twenty years, St. Francis House was blessed by the presence of a Jewish woman named Love. And you always knew Love was home because you could hear her singing Christian hymns—but always in the second person: "Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound that saved a wretch like... YOU!" Or: "What a friend they have in THEIR Jesus."

Love explained herself, "I love the tunes but it's not my faith, man."

Tim Herlihey had a bicycle shop in the garage often occupied by a cadre of bike shop boys who would work to earn a usable bicycle. That enterprise today has become Uptown Bikes, headed up by Tim's partner Maria. It is all female-run and has been voted by the Chicago Reader to be the best bicycle shop in the city two years running.

David Stein was our resident poet and woodcarver. You could often find David on the front porch or in the backyard carving a wooden spoon, a bowl, or knitting needles with a few hand tools—hoof knife, gouges, a wooden mallet. And he'd have an extra knife on hand if you wanted to join him in his art.

David also wrote many articles for the house newsletter At the Door. In one essay, he described American society as a "cult of efficiency" obsessed with speed and productivity. The life he had found at St. Francis House was a rare find—"a pearl of great beauty in the midst of rubble."

As I write these words, I realize I am making the Catholic Worker sound like a hub of creative activity, and it could be that sometimes. Mostly though, it was a lot of household chores and the sorting out of tensions between the guests and sometimes between the workers ourselves.

One time a visitor came to stay with us for a week, and when he arrived on the front porch, he announced that he was coming from the Center for Action and Contemplation in Albuquerque, New Mexico. In the midst of a bunch of guys dozing in chairs on the front porch, he was greeted with, "Well, welcome to St. Francis House—the Center for Mindless Inactivity."

But there was good reason for people to be tired and zoned out. They had spent months or years on the streets or in the shelters. People who came to our door just needed time to recover from the sheer exhaustion of it.

A woman would appear in the kitchen saying, "There's a bullet stuck in my throat."

"Did you swallow it?" I'd ask.

"No. Someone shot me with a gun, and it went down and got caught there."

"Here's a drink of water, Justina, to help wash it down," my housemate Ruth Groff would comfort her. Ruth had already lived at the house for eight years and had learned to recognize what people needed.

"On the moon, baby, on the moon. That's where my triple heart beats." Another glass of water, perhaps? No, just listen—that would be enough. And this troubled woman's poetry I remember from more than thirty years ago.

Lessons in Hospitality

Living at a Catholic Worker House is an apprenticeship in learning to relate to people whose lives have been shattered by mental illness, addiction, abuse, and desperation. "We have all known the long loneliness, and the only solution is love." Dorothy Day.

The last person I will talk about is a woman named Phyllis who lived at St. Francis House for many years—one of the long-termers. I saw her spend most days quietly reading in the front room. I heard that she had come to the house after living on the streets. She was hard to approach back then—cynical and angry. By the time I came to live there, Phyllis was a calm and wise sage. So well-read, in fact, that I could not name a classic book she had not read. She often paused her reading to listen to a fellow guest, and they were calmer in her presence. Every year Phyllis would buy high-quality Christmas gifts for the guests and workers at the house with her own money. She bought me an L.L.Bean thermal underwear top that I wore for many years.

When she moved on from the house, she left a note thanking all of us for all we had done to make her life better. It hardly felt like we had done much at all. Her note concluded with the words of St. Paul, that she had found a place "that was not forgetful of entertaining strangers and thereby had entertained angels unawares." Phyllis herself was certainly one of those.

The Peace Walk to ELF

In the summer of 1995, I moved out of St. Francis House. A group of Catholic Workers from Chicago and Wisconsin were planning a walk from Chicago, Illinois, to Ashland, Wisconsin, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The walk began at the University of Chicago—the site of the first sustained nuclear reaction on earth—and ended 450 miles away in northern Wisconsin at the US Navy's ELF facility. ELF stands for Extremely Low Frequency—the communication system that signaled the nuclear-armed Trident submarine fleet around the globe. The walk would take six weeks, and Karl Meyer lent us his Peace House mounted on a truck bed to use as a sag wagon. Karl prepared us with detailed instructions on the Peace House and all of the amenities. Perhaps the most memorable instruction were the words of Ammon Hennacy that Karl quoted from memory:

Love without courage and wisdom is sentimentality as in the ordinary church member. Courage without love and wisdom is foolhardiness as in the ordinary soldier. Wisdom without love and courage is cowardice as in the ordinary intellectual. But the one who has love, wisdom, and courage moves the world as in Jesus, Gandhi, Martin Luther King... add your own to the list.

Our six-week-long march ended at the ELF facility in which we blocked the gates and were arrested. We expected to be sentenced to at least a few months' jail time since we were all repeat offenders. Wisconsin activists like Bonnie Urfer and John LaForge had been doing six months on each charge. We were all released after a couple of days. Ashland County apparently had grown tired of housing the constant stream of activists willing to go to jail.

Challenging the Iraq Sanctions

In the late 1990s, I began helping Kathy Kelly and others with a campaign to end the sanctions on the people of Iraq. I went on three delegations to Iraq to bring in medical supplies and report on our experiences from 1997-1999. Voices in the Wilderness delegation members would load up 70 pounds of medical supplies (a token amount) as a way of publicly violating the sanctions on Iraq and inviting the US government to bring us to court for breaking the law. The penalty for traveling to Iraq was up to 10 years in prison and a million dollars in fines.

The sanctions were a silent killer in Iraq. Children, the old, the sick were dying in catastrophic numbers due to poor nutrition, contaminated water supply, and lack of medical supplies. One story brought this reality home for our delegation. We took a taxi to Al Qadisiya Hospital in a poor area of Baghdad. We saw many mothers with young children who were malnourished. Kwashiorkor was prevalent—a condition doctors told us was unheard of before the sanction regime. [Kwashiorkor is a severe form of protein malnutrition that causes swelling, loss of muscle mass, and other symptoms.]

In one ward, we met a Kurdish boy named Ali—about 8 years old. He had a treatable form of leukemia, but the treatment was unavailable now due to sanctions. At some point, Ali's father entered the room, and he became enraged at the sight of us—four strangers—foreigners for sure. "What are they doing here!"

The doctors tried to calm him by explaining we were here to help. I told the doctors to tell him it was okay for him to be angry. Someone needed to rage against the hidden crime we were seeing there.

In August 1999, Voices in the Wilderness and many Catholic Workers from Worcester, Massachusetts, held a 19-day-long fast in front of the UN to protest the sanctions. The New York Times sent a photographer to take a photo of our encampment, and we welcomed getting some press attention. No interviewer ever showed up, and the next day The New York Times published an article with the photo of us implying that our group were Saddam Hussein supporters. We went down to The New York Times headquarters to talk to the reporter of the article, but we were refused entry. "All the news that is fit to print"? How about "The truth is the first casualty of war—most of the rest are civilians."

March 19, 2003, remains the day when I felt most proud to be a Chicagoan. It was the eve of the Bush administration's "Shock and Awe" invasion of Iraq. What was expected to be a demonstration of several hundred, the night before a larger demonstration planned for the next day, turned into a groundswell of 20,000 strong who marched down Lake Shore Drive. Many hours later, after the march was essentially over, the Chicago Police Department called in reinforcements and arrested over 700 people.

Confronting Colin Powell

In 2005, former Secretary of State and head of the Joint Chiefs, Colin Powell, was scheduled to speak at Illinois Benedictine in the western suburbs of Chicago. Tim Herlihey and I went out there to hand out leaflets at the event asking Mr. Powell about his support for the war in Iraq. The event cost $100/person so we were just planning to leaflet outside and go home. Tim somehow finagled a way for us to get into the auditorium to use the washroom so we handed out our leaflets inside. People took them eagerly as if they were an event program. We ran out of leaflets and sat down to listen to what Mr. Powell had to say. He had entertaining stories about being a private in the army in the same company as Elvis Presley and later in his career driving a race car for the opening lap of the Indy 500. He also talked about the end of the Cold War in 1990 and quipped about how that almost put the Pentagon out of business—and him out of a job... shudder the thought!

At the end of his talk there was a time to ask questions so I hurried down and made it in time to be the last person in line. Most of the people ahead of me asked questions like, "What did your mother do to raise such an upstanding son?" My question for Colin Powell was, "Would you be willing to make a public apology for having deceived the US public about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq and the need to invade that country—costing the lives of thousands of US soldiers and hundreds of thousands of Iraqi lives?"

The crowd of over 800 was silent for a moment. Mr. Powell did not like my question one bit. Nor did the moderators because I found that my microphone had been cut off. In the ensuing yelling match, Powell continued to angrily resort to the criminal lies about why Iraq was an imminent threat to our country and that invasion was the only solution.

When I turned around, I was surrounded by members of the Secret Service who calmly instructed me that Tim and I would be escorted out for my own safety and that of Mr. Powell. And given the state of the crowd jeering at us, I was glad to see them there. One asked me my name and I spelled it out for him: E-V-E-R-Y P period E-R-S-O-N. Karl Meyer gets credit for that one too.

‘To Be Hopeful in Bad Times…’

Twenty-five years ago this month, my wife, Katey, and I moved down to a perfectly good "bad" neighborhood on the south side of Chicago. We have raised our two boys there—Noah now 24 and Peter, now 20 years old. Although we've been gone physically from the Catholic Worker, our time at St. Francis House continues to inform and inspire our lives. Perhaps it's what Dorothy meant when she said that the Catholic Worker "is more like an organism than an organization."

For the last few years hospitality has taken the form of greeting Central American and Venezuelan immigrants at the Greyhound Bus Station. We have made meals for the Venezuelans who were being sheltered at the police stations and connected with a WhatsApp group that was coordinating meals throughout the city.

The protests and marches against the ongoing massacre in Gaza here in Chicago have been inspiring, and I make it to many of those. Of course, it never feels like enough and it is hard to be hopeful much less joyful. And then I remember something Karl Kabat said—"Joyfulness is very important—do what you can do and then sing and dance."

In conclusion, I'll leave you with the words of the historian and long-time friend of the Catholic Worker, Howard Zinn:

To be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic. It is based on the fact that human history is a history not only of cruelty, but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage, and kindness.

What we choose to emphasize in this complex history will determine our lives. If we see only the worst, it destroys our capacity to do something. If we remember those times and places—and there are so many—where people have behaved magnificently, this gives us the energy to act, and at least the possibility of sending this spinning top of a world in a different direction.

And if we do act, in however small a way, we don't have to wait for some grand utopian future. The future is an infinite succession of presents, and to live now as we think human beings should live, in defiance of all that is bad around us, is itself a marvelous victory.

I want to thank all of you, fellow Catholic Workers, for being people in my life's journey who have behaved yourselves so magnificently.

To hear an audio recording of Michael’s talk, click here. Please note the audio is less than ideal, and picks up a few minutes into the talk.

Roundtable covers the Catholic Worker Movement. This week’s Roundtable was produced by Jerry Windley-Daoust and Renée Roden. Art by Monica Welch at DovetailInk.

Roundtable is an independent publication not associated with the New York Catholic Worker or The Catholic Worker newspaper. Send inquiries to roundtable@catholicworker.org.

Need to unsubscribe? Use the link at the bottom of this email. Need to cancel your paid subscription? Find out how here. Gift subscriptions can be purchased here.