“Peace is not possible with a faulty memory": Dorothy Day's Jubilee Witness

Intergenerational conversation between Catholic Workers young and old meditated on the prophetic life of Dorothy Day at a symposium at Manhattan University

NEW YORK

“Dorothy Day is a prophet, the great prophet of the Second Vatican Council,” said Sean Domencic of the Rechabite Catholic Worker on Saturday, as a group of several dozen Catholic Workers and friends gathered to discuss the life of Dorothy Day.

Domencic’s words offered a rousing thesis for the symposium, a collaboration of the Dorothy Day Guild and the Dorothy Day Center at Manhattan University in the Bronx. When the organizers announced the symposium last fall, they referenced the opening of Jubilee Year, and Pope Francis’ call to be “pilgrims of hope,” practioners of peace, and to embrace the works of mercy during the Jubilee Year of Mercy.

What better figure to encapsulate these works of mercy and peace than Dorothy Day, they proposed. “Dorothy understood her life as a long pilgrimage back to God in the company of the poor,” they wrote. “How does such a life speak to us today?”

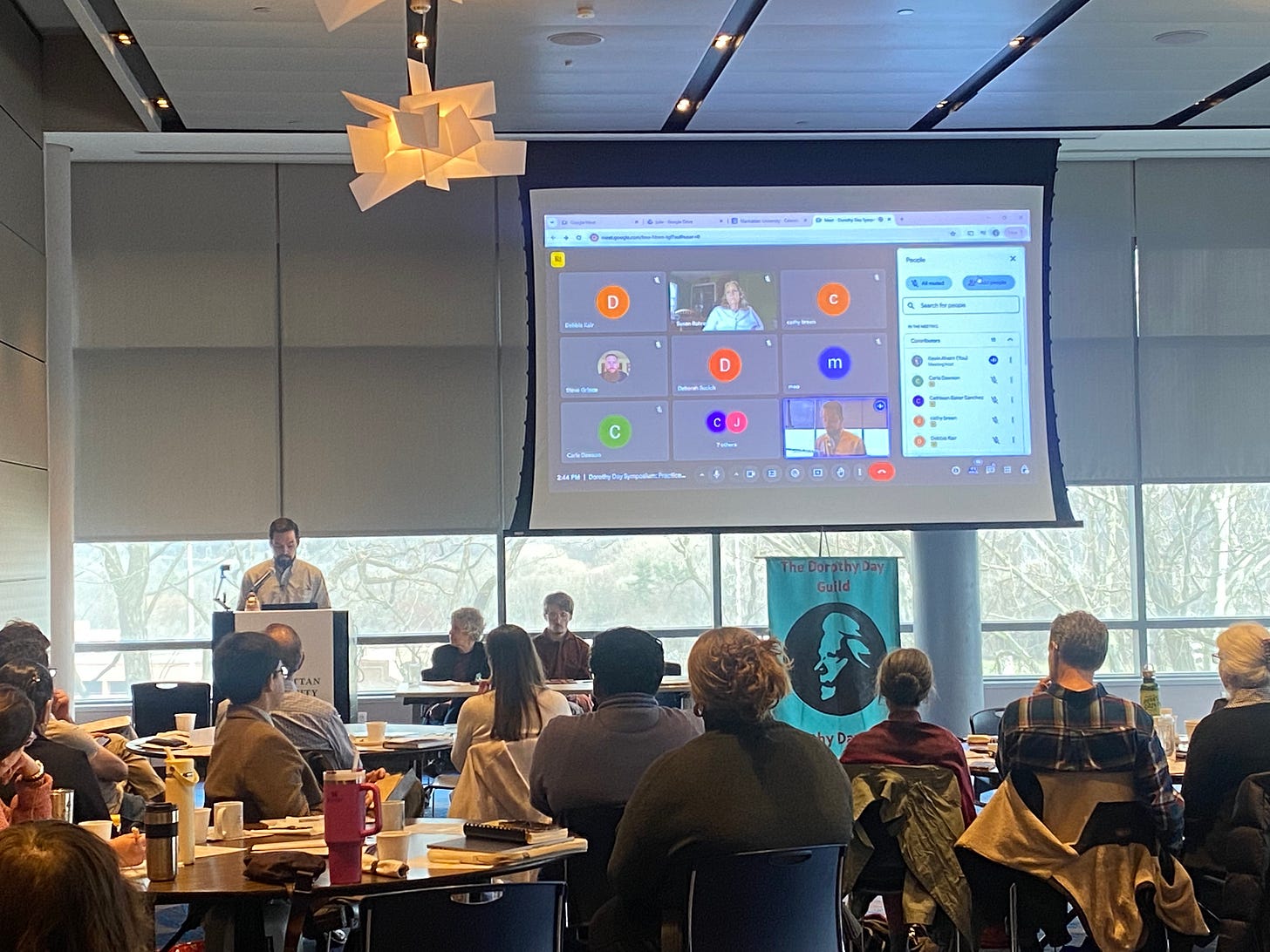

About 40 people gathered in a conference room at Manhattan University’s student center to answer that questions. Keynote presenter Robert Ellsberg, publisher of Orbis Books, and five panels discussed Day’s prophetic witness of peace-making, pilgrimage, prophecy, work, and as a promoter of the holiness of the lay vocation. An additional 15 or so guests attended virtually from all across the country.

It was a distinctly intergenerational group, with high school students, college students, twenty-somethings—like Domencic—and silver-haired veterans all represented on the five panels—called, in the Catholic Worker tradition, roundtable discussions—throughout the day.

Although Domencic’s panel was the only one dedicated to Dorothy Day as a “prophet,“ each panel highlighted a way in which Day’s life held a prophetic witness for the Catholic Church—and the entire globe—in tackling the pains and struggles of the twentieth century. As Domencic noted, many of Day’s pressing concerns: peace, the universal call of all the people of God to holiness, her ecumenism, and her commitment to the robust social reform based on a life lived in the liturgy of the church, were also key concerns of the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s.

The Second Vatican Council’s Nostra Aetate reformed the relationship of the Catholic Church with non-Christian religions, particularly the Jewish religion. Dorothy Day was certainly a prophet of the Council, then, by her solidarity with the Jews. She was a member of the first Catholics Against Antisemitism league, and, as one panelist highlighted, a friend of Jewish pacifists.

Dr. Elliot Ratzman from the University of Michigan highlighted the prophetic peacemaking witness of the Jewish Peace Fellowship, founded in 1941, who, like Dorothy Day, advocated or the wisdom of peace during a time of global war. Ratzman called Jewish pacifism “the lost Atlantis of Jewish history.”

Domencic brought up the question of if Dorothy Day herself would have spoken at Manhattan University, a Catholic college with an ROTC program, and Day had a personal commitment to refuse honors and speaking engagements from such colleges. (She famously made an exception for the University of Notre Dame’s Laetare Medal, a longer story.)

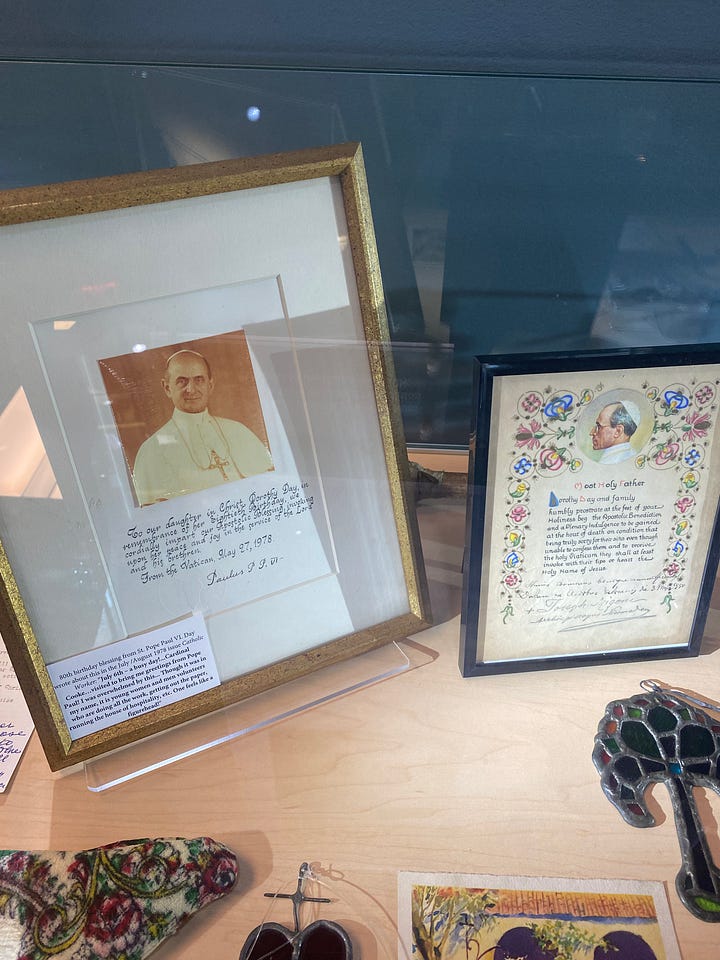

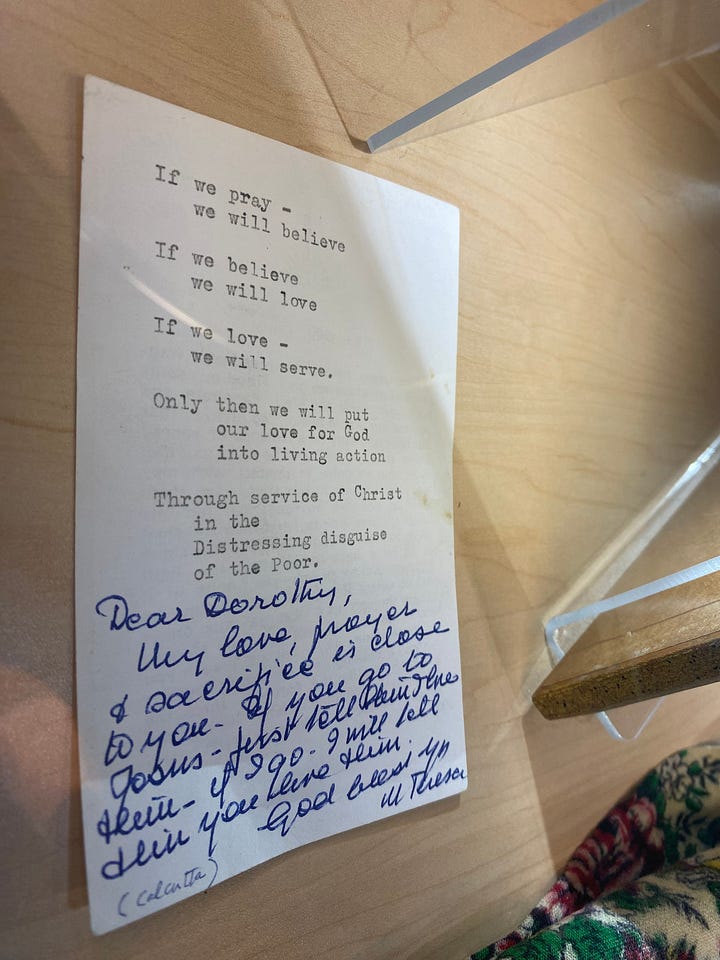

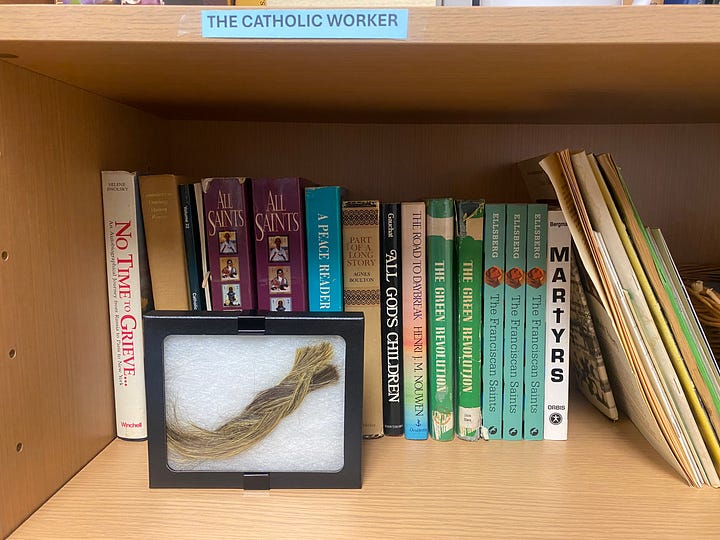

The Dorothy Day Center at Manhattan Unviersity has several artifacts of Dorothy Day’s on display: books from her room at Maryhouse, papal blessings, a handwritten note from Mother Teresa, and the clothes she was wearing during her famous 1973 United Farmworkers arrest, photographed by Bob Fitch. Recently, a community from St. Paul, Minnesota, donated a lock of Dorothy Day’s hair, much to the surprise of Kevin Ahern, the director of the center.

Despite Day’s witness to pacifism, the Dorothy Day Center is housed in a building named after a U.S. Marine who fought in Vietnam. Although such juxtapositions or contradictions are more comfortable to gloss over, Day herself did not shy away from confronting unpleasant, unjust or contradicting realities. That honesty is part of her prophetic witness, according to several panelists.

“Peace is not possible with a faulty memory,” Giulia Galeotti said, in a panel dedicated to Day’s life “on pilgrimage.” Galeotti, a journalist at the Osservatore Romano, traveled from Rome to present. She is the author of the first biography of Dorothy Day in Italian, Siamo una rivoluzione! Vita di Dorothy Day (We Are a Revolution! The Life of Dorothy Day).

Day’s journalism, Galeotti said, was an essential element of peace-making, recording the truth of the marginalized and oppressed in a world where victors write the history books.

The final roundtable discussion of the day, dedicated to Dorothy Day’s Lay Vocation featured the only all-female panel of the day. Matthieu Longlois, doctoral student at Fordham Univeristy, who introduced the panelists, said that the panel honored not just Dorothy Day’s lay vocation, but the lay vocation of all the women who have been part of the Catholic Worker movement: who have opened houses, started farms, been arrested, and done the dishes.

One of the panelists, Graceann Beckett, a current Master of Theological Studies student at Boston College’s School of Theology and Ministry, meditated on Dorothy Day’s famous dictum “don’t call me a saint.”

The original model for imagining the saints, Beckett said, was based on the patronage system of late antique Rome, where a powerful intercessor could support you or plead your cause to the emperor. (I thought of the renowned preacher, St. Anthony of Padua, who has become the powerful intercessor for helping find misplaced car keys or wallets.)

Beckett recalled her childhood Sunday school lesson that there was a distinction between “Saints” and “saints,” and that heroic holiness was reserved for “Saints.” Beckett said Day rejected this hierarchy of holiness.

Beckett discussed models of sainthood proposed by feminist theologians that could help elucidate Day’s conception of sainthood.

Day’s rejection of a sainthood set apart indicated a different kind of relationship with the saints: one of beloved companionship, “a community of love,” she said, versus a more hierarchical understanding of sainthood.

Beckett said “God’s upside down kingdom” required new ways of imagining Christian honor and power. Martha Hennessy, the final panelist of the day, also evoked the “upside down kingdom” to describe the Catholic Worker vision of community life and the call to conversion of life.

“We require war to live the way we are living,” Hennessy, peace activist and member of the Maryhouse Catholic Worker, declared in her talk. Hennessy encouraged the listeners to, like Dorothy, continue to clarify thought around the mystery of voluntary poverty. She decried the spurning of refugees pouring into the United States from a world ravaged by the excesses of U.S. imperial power, including economic sanctions on dozens of countries.

Hennessy said the life of her grandmother, Dorothy Day, taught her a much more expansive and capacious definition of family, of the domestic church, than she might otherwise have had. Contrary to ideas of “family comes first,” that have made headlines during the Trump administration’s immigration crisis, the “upside down” kingdom of God rather imagines the entire world as a guest to be welcomed into relationship, into the family of God.

These sayings are hard, who can accept them? Dorothy Day did. As the symposium explored, Day’s prophetic embrace of these hard sayings—”love in action is harsh and dreadful thing compared to love in dreams,” she was fond of quoting—has offered a rich witness for fellow pilgrims to follow.