Pope Leo XIV to Journalists: "We must reject the paradigm of war"

A reflection on Catholic Worker journalism: Pope Leo XIV asks for a journalism of peace; Peter Maurin calls reporters: "to make the right comment on the news"

Today, one week into the papacy of Leo XIV, marks the 134th anniversary of Rerum Novarum, the landmark Catholic Social Teaching encyclical on the rights of workers by his predecessor Pope Leo XIII. May 15 also marks the day, 76 years ago, when Peter Maurin, co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement, died in Newburgh, New York, at the Catholic Worker’s Maryfarm.

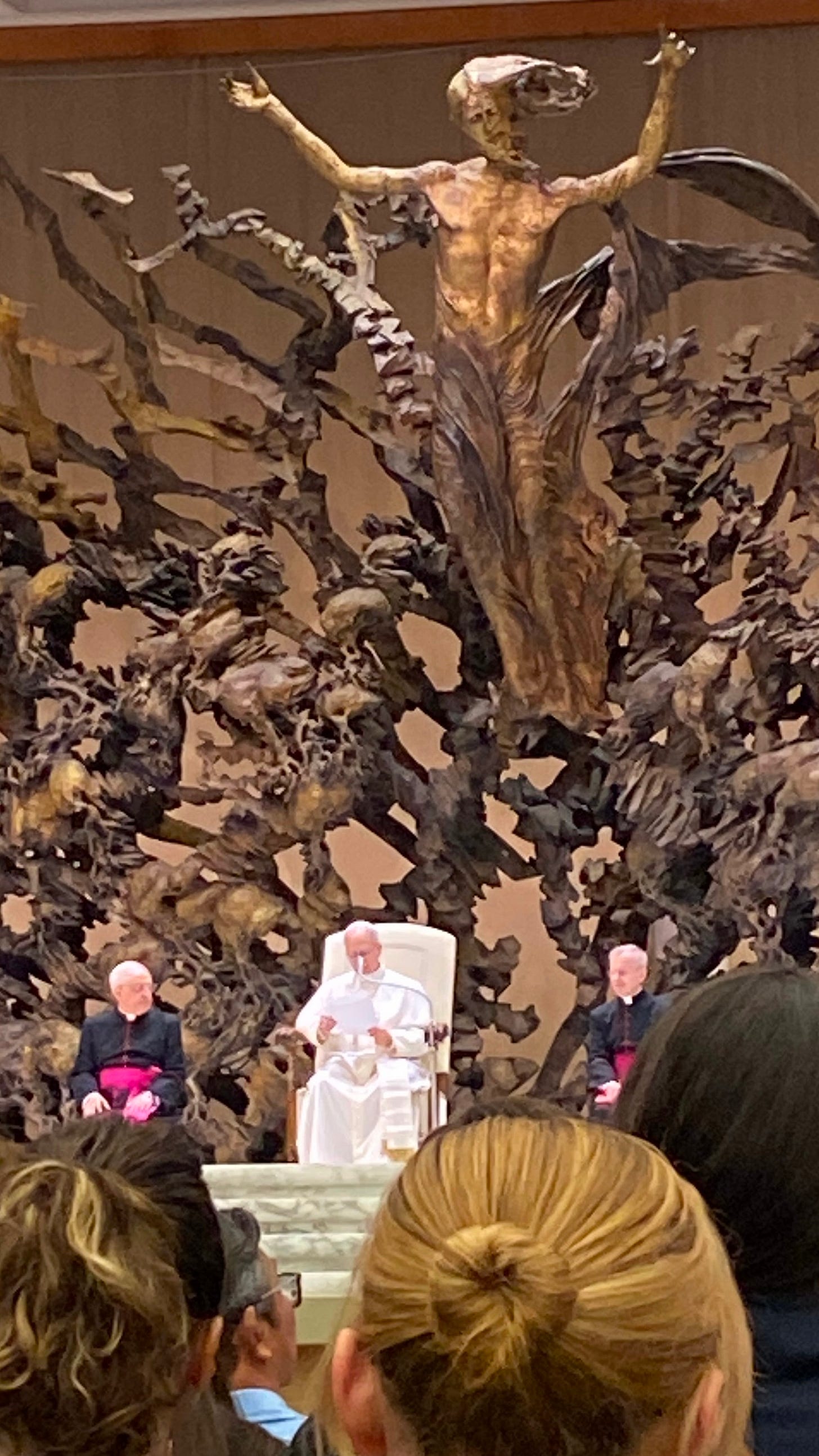

On Monday, I attended Pope Leo XIV’s audience with journalists in Paul VI Audience Hall in Vatican City. It was the sort of event where you wait in various lines and holding spaces for four times as long as the audience. But it was also one of those events that was very much worth it.

In his short address, Pope Leo XIV laid out his invitation to the media to practice a “different kind of communication.”

“Peace begins with each one of us,” Pope Leo XIV said, “In this sense, the way we communicate is of fundamental importance: we must say ‘no’ to the war of words and images, we must reject the paradigm of war.”

Well. If those weren’t words meant for Catholic Workers, I don’t know what is. Nonviolence is often clear at a global scale—we see the horrors of famine in Gaza, nuclear war, and the brutal fascism practiced on everyone from immigrants to federal judges (one who was the former director of Catholic Charities in Milwaukee), from first-time fathers to elected officials—in our own country—and they are clearly wrong.

Nonviolence at a more personal scale is sometimes the hardest to practice. Being a peacemaker is a muscle that demands daily practice. Although it is easy to grow angry or fearful at the wars being waged inside and outside our country, the act of peacemaking does not stem from anger or rage or the desire to wage an existential battle against evil. It is fostered by the will to peace, the demand of active love, the belief in the absolute human dignity of each of our neighbors.

“The greatest challenge of the day is: how to bring about a revolution of the heart, a revolution which has to start with each one of us,” Dorothy Day wrote in Loaves and Fishes, her 1963 story of the Catholic Worker movement.

Being a peacemaker takes daily practice to reject the many paradigms of war we have learned: How dare they interrupt me? Why doesn’t X agree with me? There’s not enough for everyone. You have to earn worthiness and dignity.

Being a peacemaker means saying “no” to the war of words that harm, that tear apart another person, that cut others down, that deny the truth that they are also an image of God. Being a peacemaker takes daily practice—to exercise that muscle that says: that person is my problem, their problem is my problem, that grief is my grief, and I will not walk by without stopping, I will not pretend their wounds are not mine also. The Good Samaritan is a peacemaker.

Pope Leo XIV invited journalists to a practice of communication that allowed for the diversity of multiple viewpoints, which “does not seek consensus at all costs.” That promotes diversity and dialogue but does not perpetuate the wounds of division, “does not use aggressive words, does not follow the culture of competition and never separates the search for truth from the love with which we must humbly seek it.”

Journalism, as a spiritual work of mercy—comforting the sorrowful, counseling the doubtful, instructing the ignorant, admonishing the sinner—was the first mission of the Catholic Worker movement. As Pope Leo XIV reminded journalists, how and why you report something is just as important as what it is you are reporting. The pope’s words brought to mind Peter Maurin’s Easy Essay, “The Thinking Journalist.” In his 1937 essay, Peter describes the sort of reporting that is at the heart of The Catholic Worker literary tradition:

Good journalism

is to give the news

and the right comment

on the news.

The value of journalism

is the value of the comment

given with the news.

Good journalism, Peter Maurin says, makes a good comment on the news of the day, shading in the full picture, so you can see it clearly.

The media landscape has grown more polarized, and news outlets in the United States seem to be quickly losing consensus on what the facts of a given story even are—the “Tower of Babel” Pope Leo XIV called it—the question of what an outlet’s editorial vision, commitment, or underlying slant is even more important. What is the “right comment” on the news?

Peter Maurin called for “clarification of thought,” but the internet calls forth a multiplication of thoughts—not all of them good, an increasing number not even human-generated. AI-generated content on the internet has grown 8,000% with the rise of ChatGPT, according to Tech World News. Peter Maurin called for the laity to bring “order out of chaos,” but so much of our glutted online media landscape just swirls chaos into cacophony. We open up Pandora’s Box and find that we are drowning in words and images, but how many of them are true? How many are algorithmically delivered to us to infuriate or distress us? How many comfort us, console us, assure us that there is mercy for all sinners, and we are all called to be heroic saints?

In 2012, then-Rev. Robert Prevost, OCA, spoke to Catholic News Service about the media landscape, being a discerning reader, and the importance of identifying the implicit or explicit bias of the news source. This was, of course, before the maximum peak users of Twitter in 2022, before BeReal or Snapchat or Instagram Stories, or TikTok. It was before the Associated Press was kicked out of the White House Press pool.

It was, in some ways, a simpler media landscape. Now, the Pandora’s Box of the World Wide Web inundates readers with often faulty or inane information as soon as we open our phones or laptops.

“We are living in times that are both difficult to navigate and to recount,” Pope Leo XIV said. He called, as he has multiple times already in his papacy, for courage in facing the challenge of the moment. He praised the courage of journalists who have been killed because of their work to “defend dignity, justice and the right of people to be informed, because only informed individuals can make free choices. And he expressed the church’s solidarity with journalists in jail.

The Committee to Protect Journalists has already counted 21 journalists killed in 2025—15 of them in Israel and Palestine. This is after a bloody record-high of 124 journalists killed worldwide in 2024—70% of them killed by Israel’s military. The committee’s census counted 361 journalists incarcerated in 2024, with China, Myanmar and Vietnam topping the list of countries with journalists in prison.

“Communication and journalism do not exist outside of time and history,” the pope said, calling for courage in the face of challenges rather than “mediocrity.” He quoted St. Augustine: “‘Let us live well, and the times will be good. We are the times.’”

The pope’s name was his own response to the signs of the times. In an address to the College of Cardinals, the new pope said he chose his name in honor of Leo XIII, and the encyclical of Rerum Novarum, which guided the Church in its social preaching and teaching throughout the first industrial revolution. He hoped to reiterate this social teaching during this new industrial revolution, a world re-shaped by “artificial intelligence” and high-powered computing programs that is being contracted to defense agencies and used in war—Israel’s military identified human airstrike targets with an artificial intelligence program—without an iota of discernment or concern for human dignity.

“In looking at how technology is developing, this mission becomes ever more necessary,” Leo XIV said. He was thinking in particular of “artificial intelligence, with its immense potential, which nevertheless requires responsibility and discernment in order to ensure that it can be used for the good of all, so that it can benefit all of humanity.” He is right to call for discernment. Harvard Business Review has already studied how artificial intelligence has impacted labor.

Missing in the accelerating rush of the past three decades of digital innovation seems to be the simple question: What does this machine do to our humanity?

This is a question that Peter Maurin certainly posed to the many out-of-work Americans, made homeless and jobless, as the economic system that Leo XIV warned about collapsed on Black Friday. Before Peter Maurin wrote his Easy Essays, he traveled through the United States for a decade and change, working on the railroad, in coal production. He saw firsthand what life with the machines was doing to the humanity of his fellow workers.

And, as Dorothy Day wrote in Loaves and Fishes, Peter Maurin’s philosophy of work was often a hard message to many at the Catholic Worker—completely counter-cultural to the American culture of competition and scarcity. “Fire the bosses” seemed less possible than picketing the corporation and to work without wages, offering one’s labor as a gift, seemed like a recipe for an early death. But, as the machines that have promised efficiency, easy labor, and cheap goods, seem poised to eliminate human labor and creativity, Peter Maurin’s questioning of the entire industrial system seems, perhaps, a bit more prophetic.

“What an inspired attitude Peter took in his painful and patient indoctrination,” Day wrote, “and what a small part of it we accepted.”

Writing is essential to The Catholic Worker’s mission. Writing is a spiritual work of mercy that, as Peter Maurin would say, “arouses the conscience.” Peter Maurin’s provocations were meant to do exactly that: to ask: why are things the way they are? Are things as they should be? If we were to take our faith’s values at faith value, what sort of society might we make in place of the one we have now?

As Dorothy Day wrote, “If we do not keep indoctrinating, we lose the vision. And if we lose the vision, we become merely philanthropists, doling out palliatives.” The work of hospitality, the nonviolent resistance to evil, the corporal works of mercy spring out of the life of the spirit and the spiritual works of mercy. Dorothy Day called it “the primacy of the spiritual,” a key concept of Emmanuel Mounier’s personalism.

This primacy of the spiritual and the commitment to Catholic Social Teaching was the editorial lens of the newspaper Dorothy Day started. Reading those explosive—dynamic—first editions, the reportorial gloss of solidarity, subsidiarity, human dignity, and the common good is crystal clear and electrifying. It’s a tradition to aspire to.

The real and active love that Dorothy Day so often spoke of, that she lived, and that infused her writing, is a love that comes from living in solidarity with the suffering she writes about. Day did not write about the injustices of the world as a marketable front-page news item, something to catch a customer’s eye, a story to be devoured and consumed, far removed from one’s own suffering. Rather, in the tradition of The Catholic Worker, the journalist writes a position of suffering-with—from solidarity, from compassion—“gathering the voices of the weak who have no voice,” as Pope Leo XIV said.

Writing, as a form of clarification of thought, was the first pillar of the Catholic Worker program. Clarification of thought was a necessary first step, Peter Maurin said for Catholic Workers to have a “theory of revolution” or a “theory of labor” to organize themselves, so that they could organize others.

Writing, Peter Maurin believed, was an extremely effective way to promote this self-organization for the reconstruction of the social order. As he wrote in “The Thinking Journalist”:

By affecting public opinion,

the thinking journalist

is a creative agent

in the making of news

that is fit to print.

The thinking journalist

is not satisfied

to be just a recorder

of modern history.

The thinking journalist

aims to be a maker

of that kind of history

that is worth recording.

“We are the times,” as Pope Leo XIV said. I don’t know if he’s ever read Peter Maurin’s “The Thinking Journalist” but he and Peter Maurin seemed like they were drawing water from the same well.

The Catholic Worker has always written about the sufferings of the world, but its writings—and the writings of many other newspapers and newsletters throughout the country—have proposed to a broken society that another way to conduct our business, housing, agriculture and economic lives is possible.

A communication for peace, a disarmed journalism, “allows us to share a different view of the world and to act in a manner consistent with our human dignity,” Pope Leo XIV said on Monday.

Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day did not think that society needed to just be touched up, that a few more people needed to be included in the system to make it just, a few tweaks needed to relieve everybody’s suffering. They believed that the system we lived in needed to be remade radically—from the root. They tried to reconstruct that social order in the shell of the old broken one, just like the first Christians, and their writings inspired many others to do the same. Their writings did not just record the problems of modern history but made history—a kind of history worth recording.

“Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day did not think that society needed to just be touched up, that a "They believed that the system we lived in needed to be remade radically—from the root. They tried to reconstruct that social order in the shell of the old broken one, just like the first Christians, and their writings inspired many others to do the same. Their writings did not just record the problems of modern history but made history—a kind of history worth recording.”

How about reconstructing the Catholic school system “in the shell of the old broken one”?

“A preferential option for the poor” should be maintained in our Catholic Schools. If we find that we cannot afford to keep our schools open to the poor, the Church should be ready to use its resources for something else which can be kept open to the poor. We cannot allow our Church to become a church primarily for the middle-class and rich while throwing a bone to the poor. The priority should be given to the poor even if we have to let the middle-class and rich fend for themselves.

Practically speaking, because the Catholic Schools have become so expensive that they now serve primarily, the middle class and rich, while the poor are left in the public schools; the Catholic schools should give up general education in those countries where the State is providing it. The resources of the Church could then be focused on “Confraternity of Christian Doctrine” and other programs which can be kept open to the poor. Remember, the Church managed without Catholic schools for centuries. It can get along without them today. The essential factor from the Christian point of view is to cultivate enough Faith to act in the Gospel Tradition, namely, THE POOR GET PRIORITY. The rich and middle-class are welcome too. But the poor come first.