Precarious Spaces

Three articles from the London Catholic Worker newsletter take us into the precarious spaces inhabited by those on the margins of society.

This is CW Reads, the Thursday long-read edition of the Roundtable newsletter. In this issue, we feature three articles from the latest newsletter of the London Catholic Worker. If you prefer to read the entire thing as a PDF, you can do that here.

In “Kindness in Precarious Spaces,” Br. Johannes Maertens shares scenes from a recent visit to the Dunkirk refugee camp, where he works with an organization called Art Refuge.

In “Externalisation,” Thomas Frost offers a primer on the British policy of “externalizing” its borders for the purpose of enforcement—but not asylum.

And in “Muggings,” Anne M. Jones wrestles with how best to respond to her experience of “soft muggings,” especially in light of St. Francis’s call to embrace poverty.

These articles are reprinted with permission from the London Catholic Worker; you can find out how to support them at the end of this newsletter. British spellings and punctuation have been retained. Enjoy!

Kindness in Precarious Spaces

Br. Johannes Maertens on his work with Art Refuge in Dunkirk and Calais.

by Br. Johannes Maertens

A few weeks ago, I was in the Dunkirk camp, where I regularly join Art Refuge* in their work with the medical NGO Doctors for the World. The weekend before, around 1,000 people had crossed the English Channel from northern France in small boats, and four people, including a child, had lost their lives. In Dunkirk, the team informed us that early that morning the police had started ‘le démantèlement’ or the ‘clearing’ of the refugee tents and camp. We didn’t really know how the mood or atmosphere would be. Would there be tensions between the communities? Between the smugglers? Or between individuals?

On the way to the camp, with our caravan of NGO vans and the ambulance, we saw groups of refugees standing on one side of the busy dual carriageway, all looking in the same direction. They were watching, from a distance, as their last dwelling places—tents, campfires, sleeping bags, or anything else they hadn’t been able to take with them—were being removed into small waste vans. It was probably not the first time they had been exposed to this, nor was it the first time I had witnessed it, but even if people are staying in places where they aren’t supposed to be, seeing people’s improvised dwellings or shelters being dismantled and disappear is not easy. Perhaps the refugees were standing there wondering, ‘Under which blanket will I sleep tonight? Will I be able to find a dry place? My good boots were in there,’ and so on. Refugees are often people already struggling with being uprooted. This does not help.

The place where the NGOs set up the distribution was already very busy; more than 800 breakfasts had been given out by the charities. As we tried to set up alongside the others, refugees began coming to the team for medical help. With Art Refuge, we have a very long van at our disposal, with long tables. We tend to use both inside and outside spaces when it isn’t raining. One of the ‘tools’ we use is a very large map of the world, which we lay on the ground, not too far from the van. As soon as I had laid the map (which consists of three large parts) on the ground, refugee men gathered around it. Standing at the edge of the world map makes you stop and look, or, you could say, take a step back and look at where you are.

‘Where is Afghanistan?’ one of the young men asks me. I am sitting on the map in the ocean area—you don’t want to sit on someone’s country—so I glide my finger towards Afghanistan. His friend asks, ‘Where is the UK?’ I point to that little island off the coast of Europe, more towards the middle of the map. With their fingers and mine, we start retracing the route they took to Dunkirk: Afghanistan, Iran, Tehran, Turkey, Greece, Italy, and France. On our very large world map, the distance between Dunkirk and London is about only an inch and a half.

They have travelled a long way, these young lads. They have seen different worlds and are now in a wet, cold tent camp in the dunes of northern France. Several had journeyed for a year, three years, or even longer. Only a handful had been ‘on route’ for a few months. The map and some of the other materials we use make people ‘time travel,’ as my colleague Miriam Usiskin likes to call it. In their minds, people travel back to where they came from (often home), they look at where they are going, and at where they are now. I think the map helps put things in perspective—what they have been through. All the materials and the setup we use have been selected over many years and have their ‘art-therapeutic’ significance, but that is for the art therapists to explain, not me.

Now, a young South Sudanese Christian and his friends show me proudly where they are from: South Sudan (although he mentions he was born in Khartoum). The group of young men were all around 15 or 16 when they left South Sudan for Sudan, through the desert to Libya, to Tunisia, being pushed back from Tunisia into the Libyan desert, being pushed back to Tunisia, and back to Libya again. Finally, crossing the dangerous journey on the sea to Lampedusa, then onto mainland Italy, and now, last week, Dunkirk, France. Their English was good, from their school days. I began to understand that it had been a long journey; they had been on the road for six years! They had a smile on their faces, like most young people in the world. Tunisia was ‘difficult,’ Libya ‘difficult,’ ‘very difficult.’

My colleague, Bobby Lloyd, had brought me some coloured tape, and we plotted out on the map the route these five or six young men had taken. A young man from Kurdish Iraq started mapping out his route and explaining where he came from, which route he took, and why he had left Kurdistan (bombings by the Turkish army). He came by the Serbian route. He was not alone—others from Kurdish Iran and some Afghans had come through Serbia and Eastern Europe. Even some Ethiopians had come through the Belarusian-Polish border, where they were hit and pushed back over the border by the Polish border force. Some had tried to cross the border nearby in Lithuania—but that was too bad. Not only did they get hit, but some said refugees were tortured there—their fingernails were pulled out.

The map began to fill up with all different colours of tape, representing the routes our young men had taken and the stories they were sharing. One of the Ethiopian young men said to his friend, ‘Your Vietnamese friend, where did he come from?’ and I quickly showed them Vietnam on the map. ‘So far!’ ‘Yes, it is,’ I said. So much further than they had already come. That day, we only saw one Vietnamese refugee, but Dunkirk has, for a long time, had Vietnamese refugees passing through.

Sometimes people stand there silently, or tell each other—and us—parts of their stories. And of course, they look at the one-and-a-half-inch distance between Dunkirk and London. People from different continents even listen to each other’s stories. Others help translate. It gives people a different perspective, with everything they have been through, and all the hopes or hopelessness they carry with them.

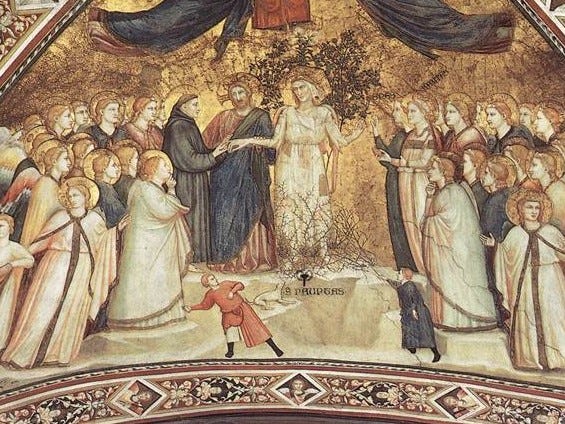

Maybe plotting the routes on the map also ‘roots’ people in a certain way? But like my colleague Miriam Usiskin remarked in our debriefing after the work in the camp: ‘Kindness’—there was kindness around. Even if we were in a more-than-precarious place, in a very difficult camp, when these young men gather around the map, or the young men, women, and children gather around our community table that we had set up, there was a certain kindness, hope, and even joy. And that made me think of the Gospel reading of Emmaus, which recounts the journey of two disciples on the road to Emmaus, unaware that they are accompanied by the resurrected Jesus. Both the disciples and the refugees are on a journey, burdened with uncertainty and loss, yet yearning for hope and safety.

For refugees, their journey often feels like an endless walk, a dangerous walk to Emmaus, filled with despair and uncertainty. But sometimes, where people meet and share their hope, kindness can be born. And from that hope and kindness, healing and a sort of resurrection can come.

In someone's journey, our mutual acts of kindness can be the beginning of something much greater. Maybe standing here today doesn’t immediately change the dreadful reality or our UK and European policies—but our simple acts of kindness might save or change a person’s life.

*On a monthly basis, I try to join the Northern France team of Art Refuge in Dunkirk and Calais. The team is led by Bobby Lloyd, visual artist and art therapist, and Miriam Usiskin, art therapist and Senior Lecturer at Hertfordshire University, MA Art Psychotherapy. Art Refuge uses art and art therapy to support the mental health and well-being of people displaced due to conflict, persecution, poverty, and climate emergency, in the UK and internationally. More info at www.artrefuge.org.uk.

Externalisation

Thomas Frost on our national failure to meet Christ in the stranger.

by Thomas Frost

Those of us who are not saints are likely to find ourselves, eventually, asking the Lord ‘when did we see you a stranger?’ (Mt 25:44) We know in principle that what we do for the poor we do for Christ, but the definite moments when it becomes clearly imperative to act on that principle come up so rarely that, in practice, we generally do less than we should. We might recognise refugees and illegalised migrants today as some of those people among whom Jesus told us we should expect to find him, but we so rarely come face-to-face with them that we are not often so moved. Moreover, the state has set up its border regime in such a way as to make it as difficult as possible for us to be good.

As far as possible, asylum seekers are prevented from reaching Britain in the first place, but are kept in Calais, so that when the French police destroy the belongings of migrants and leave them to sleep in the cold, when they sink small boats at sea and leave people to swim back to shore, it is not really treated as a political issue here in Britain, despite the fact that our government directly funds it, and created in the first place the exceptional situation whereby the border is moved to Calais for the purpose of enforcement but not for the purpose of asylum. Those asylum seekers who do manage to reach the UK are without exception detained on arrival, and generally placed in an immigration detention system designed to isolate them. As far as possible, irregular migrants and the violence used against them, paid for by you and me, are kept invisible, so that people don’t, on the whole, think of these things as being done to human beings, but keep thinking in an abstract way about ‘securing the border’. This is one of the benefits of ‘externalization’ for the authorities.

But there are limits to what the authorities can do in countries like Britain and France, with the remnants of a commitment to humans rights and a relatively open media able to report on abuses. Consequently, the policy of British and European governments is increasingly to outsource border violence to those governments and other groups which can get away with it. In recent years this has involved substantial payments to the border agencies of authoritarian and semi-authoritarian states along the north African coast through which many migrants travel in hope of reaching Europe via the Mediterranean. In September, Keir Starmer visited Rome to praise the supposed successes of these initiatives in reducing the number of those crossing the Mediterranean, and announced that £4 million would be given by the British state to the Rome Process, one of the funnels through which aid to these agencies is poured.

We find that those crossing the Mediterranean are often more frightened of being returned to these countries than they are of dying at sea, to the point of refusing to send out distress calls until they are out of Tunisian or Libyan waters. The Tunisian government has openly adopted a practice of systematic pushbacks into the desert — men, women and children are driven out into the Sahara and abandoned, often with no food or water and with their phones confiscated.

They are left to walk for days back to the coast or die in the attempt. Several mass graves have been found in the Sahara but there is no way of knowing how many have been murdered in this way, partly because the Tunisian government makes it virtually impossible for NGOs to operate there. A recent UN report found that twice as many people now die in the Sahara as drown in the Mediterranean. In exchange for this contribution to Europe’s border security, European governments have given hundreds of millions of euros to the Tunisian government in the last few years, including €105 million in 2023 specifically to fund Tunisian border control, in full knowledge of the methods used.

The situation in Libya is, if anything, even worse. There is no centralised coast guard or border force in Libya, which has been split between two rival governments since the civil war, each of which is effectively a coalition of smaller militias; the role of a coast guard is undertaken by these various militia groups. Those migrants who are captured while travelling through Libya, or intercepted by the so-called coast guard at sea, suffer what a UNHRC report, published last year, described as ‘an abhorrent cycle of violence’. The report found ‘that migrants across Libya are victims of crimes against humanity and that acts of murder, enforced disappearance, torture, enslavement, sexual violence, rape and other inhumane acts are committed in connection with their arbitrary detention’— sexual slavery is also systematic. It is normal for migrants detained in Libya to be held for ransom, either from their own funds or their relatives’, to the extent that forced labour and extortion have become what the report calls a significant source of revenue for Libyan militias and state institutions.

Facilitating this, European governments, including the British government, have given tens of millions of euros worth of aid to Libyan groups in the last few years to fund their actions at the border. Furthermore, European border agencies routinely share the coordinates of migrant boats with the so-called Libyan coast guard, even when merchant vessels and civilian rescue ships are much closer, because civilian ships would be unable to return rescued people to Libya under international law, as an unsafe country. As an example of what happens to those returned there, the UNHRC report cites a documented instance of a boy, a refugee detained in Ayn Zarah in Libya, who having been tortured, and in immense pain, hung himself. His body was left hanging in front of other migrants for a day and half before it was taken down by guards. There are countless similar stories. In the same month as this report was published, the British government announced another £1 million in funding for Libyan border authorities.

All this is being done, at least in part, on our behalf and with our tax money. It would not be accepted if it was happening in this country, but because it is being done far away, to people who are not deemed to matter, it is barely even reported on. It happens with the tacit acceptance of people in this country because we allow migrants to be marginalised — because, for the sake of a sense of security here in the centre, we are willing to overlook the violence at the border.

This article was first given as a reflection at a monthly vigil outside the Home Office on Marsham Street, during which we name and mourn those killed each month crossing European borders. I hope that we thus play some small part in opposing the border regime. Christians in this country have an obligation to rehumanise in the public mind those who are dehumanised by state policy. We have as much as we can to bring people who are marginalised into the centre of our communities. We have to keep talking about these things in the centres of power, of government, of the media, of the churches, of our own communities.

Our religion, after all, began with a crucifixion. It was such an awful and humiliating form of death, as far as the Romans were concerned, that the crucified person suffered a sort of social death as well— they were placed in a state of exception, as someone you couldn’t relate to socially in a normal way. On the edges of settlements, they were marginalised in every possible sense. And when God came into the world that was where he chose to place himself, and for two thousand years we have been putting the cross right at the centre of our worship— that is what Christianity is. We are hypocrites, then, if we centre the cross but don’t centre those being crucified at this moment. If there’s any comfort to take from all this it’s the certainty that, however successful or otherwise we are at this work of social rehumanisation, God will always be successful, because he himself won that victory on the cross. As Reverend Munther Isaac said at Christmas, God is under the rubble. God is in the deserts, in the detention centres, and at the bottom of the sea. If we want to find him, that’s where he’ll be. Jesus remains at the cross.

Muggings

Anne M Jones reflects on the dilemma of being shortchanged by those short of change.

by Anne M. Jones

Peter Maurin’s Easy Essay on St. Francis, printed in this year’s Summer LCW newsletter, refers to Johannes Jorgensen writing that “St. Francis desired that men should give up superfluous possessions.” Similar words are constantly on my mind as I go about my daily business in London. I am typical of the guilt-ridden middle classes, all too aware of our good fortunes, born in the right generation at the right time. 1941 might seem an unlikely year, but I was fortunate enough to be geographically and socially placed to escape the worst events and their aftereffects. I am daily grateful for how things have worked out for me in the eighty years since.

A daily preoccupation of mine is how to give to the poor without becoming complacent, conceited, or indifferent. Living in London over the past 18 years, I’ve become increasingly aware that dropping £1 into a beggar’s plastic cup might be repeated ten times within half an hour, which is a shocking indictment of the steady deterioration in life for some people in my city. So, like most of my friends, I now restrict my offering to one a day and focus on the small, organised charities that have sprung up in recent years to reach wider groups of marginalised people. But I’ve been “softly” mugged (meaning no threats, weapons, or violence were involved) at least twice.

On the first occasion, I was withdrawing money from a cash machine when a man tapped me on the shoulder, distracting me momentarily. He then snatched my card and ran off. I immediately rang my bank to stop the card, but the thief, having memorised my PIN number, had already stopped at another cash machine a few yards away and withdrawn £200.

An off-duty policeman had witnessed the entire incident and insisted on taking me to the local police station to report it. When I later commented, “What a sad way to lead a life,” the policeman gave me a look of sheer disbelief. He had no time for “that sort of scum who need locking up.” The loss was later covered by my friendly, helpful bank, so I was completely unharmed.

Then, the other day, I was walking along an unfamiliar street when a distraught woman rushed up to me and insisted that she wasn’t asking for money, but could I please exchange some cash for a ten-pound note? She claimed the hostel she needed for the night refused to accept cash. Though this explanation seemed odd to me, I wanted to be helpful. Looking into my bag, I did indeed have a ten-pound note, which I gave her. She began pouring the coins into my hand but suddenly switched to pouring them into my handbag.

I walked away, feeling smug (as I tend to after thinking I’ve been helpful), and decided to check the coins. Somehow, by sleight of hand, she had given me only £2. Over the next few hours, I cursed myself for my own stupidity. I warned other people, some of whom said this was an old trick, while others advised, “Call the police.” Nonetheless, I decided to return two days later, and there she was—same place, approaching passers-by with a handful of coins, same patter. I went up to her and introduced myself, whereupon she beamed and said, “Thank you, darling,” and attempted to kiss me on the cheek. I stepped back and said, “You short-changed me.”

“Oh dear, did I darling? Let me repay you,” she cheerily replied.

“No, I wouldn’t dream of taking it, but I think you need to get your life sorted out,” I sternly told her, at which point she turned her back and walked off. Which is what I should have done as soon as she approached me. But, as I said, the urge to be helpful is in the DNA of most of us. That ten-pound note, in any case, represented ten days of not dropping a coin into a plastic cup, so in that sense, it was superfluous to me.

The need to live on one’s wits has been around since the beginning of society, and before the Welfare State, it was probably the modus vivendi for many. But this incident has made me wonder how many of us, in fact, graft from others perceived as far stronger than ourselves. I admit, I enjoy taking home souvenir table napkins and sugar packets if ever I’m invited to posh places to eat (increasingly rare these days, sadly). The recent scandal about our Prime Minister’s wife accepting expensive clothes from a wealthy donor makes me wonder about the whole business of taking from others. I wonder why the acceptance of something we cannot get for ourselves is seen as self-enhancing.

The young man involved in my first mugging was, according to the policeman who kindly helped me, part of a large gang operating all over London for a gangmaster. Some months later, most of them were jailed for 18 months to 4 years. The cost to the state would have been hundreds of thousands, and I wonder whether these desperate men benefited from prison. The second mugging involved a very desperate woman, and it has left me wondering whether I owe her any further obligation. She is clearly in deep trouble, and I know of several places where she might turn for constructive help—should she want it. Equally, I have to recognize that she is a self-determining human, clever and skilled in her strategies to survive in a difficult life.

My social work days are well and truly over, and I am now at the stage of trying to shed as many superfluous belongings as I can bear to part with. In the process, I am discovering that much of my stuff holds deep sentimental value, so my drawers and bookshelves remain stuffed, though no longer over-stuffed. I have to restrain myself from buying things that look lovely in the shop (charity shops, these days). In pondering these things, I discover—not without a wry smile—that I am facing my own deep flaws: greed and covetousness. It’s an interesting revelation. While I am no longer of the self-flagellation mindset, at times it remains irresistible, and I conclude: “Must try harder.”

I wonder what St. Francis would say?

If you would like to support the London Catholic Worker…

To make a donation to the London Catholic Worker, visit the donations page on their website.

About us. Roundtable covers the Catholic Worker Movement. This week’s Roundtable was produced by Jerry Windley-Daoust and Renée Roden. Art by Monica Welch at DovetailInk. Roundtable is an independent publication not associated with the New York Catholic Worker or The Catholic Worker newspaper. Send inquiries to roundtable@catholicworker.org.

Subscription management. Add CW Reads, our long-read edition, by managing your subscription here. Need to unsubscribe? Use the link at the bottom of this email. Need to cancel your paid subscription? Find out how here. Gift subscriptions can be purchased here.

Paid subscriptions. Paid subscriptions are entirely optional; free subscribers receive all the benefits that paid subscribers receive. Paid subscriptions fund our work and cover operating expenses. If you find Substack’s prompts to upgrade to a paid subscription annoying, email roundtable@catholicworker.org and we will manually upgrade you to a comp subscription.