Slowly, We Become Community

Three short essays about how personalism builds community...and even found family. Plus, Dorothy on Peter Maurin's "program."

Personalism is a core tenet of the Catholic Worker. Today, we have three short essays that give us a glimpse into what that actually looks like when it's lived out in a Catholic Worker setting:

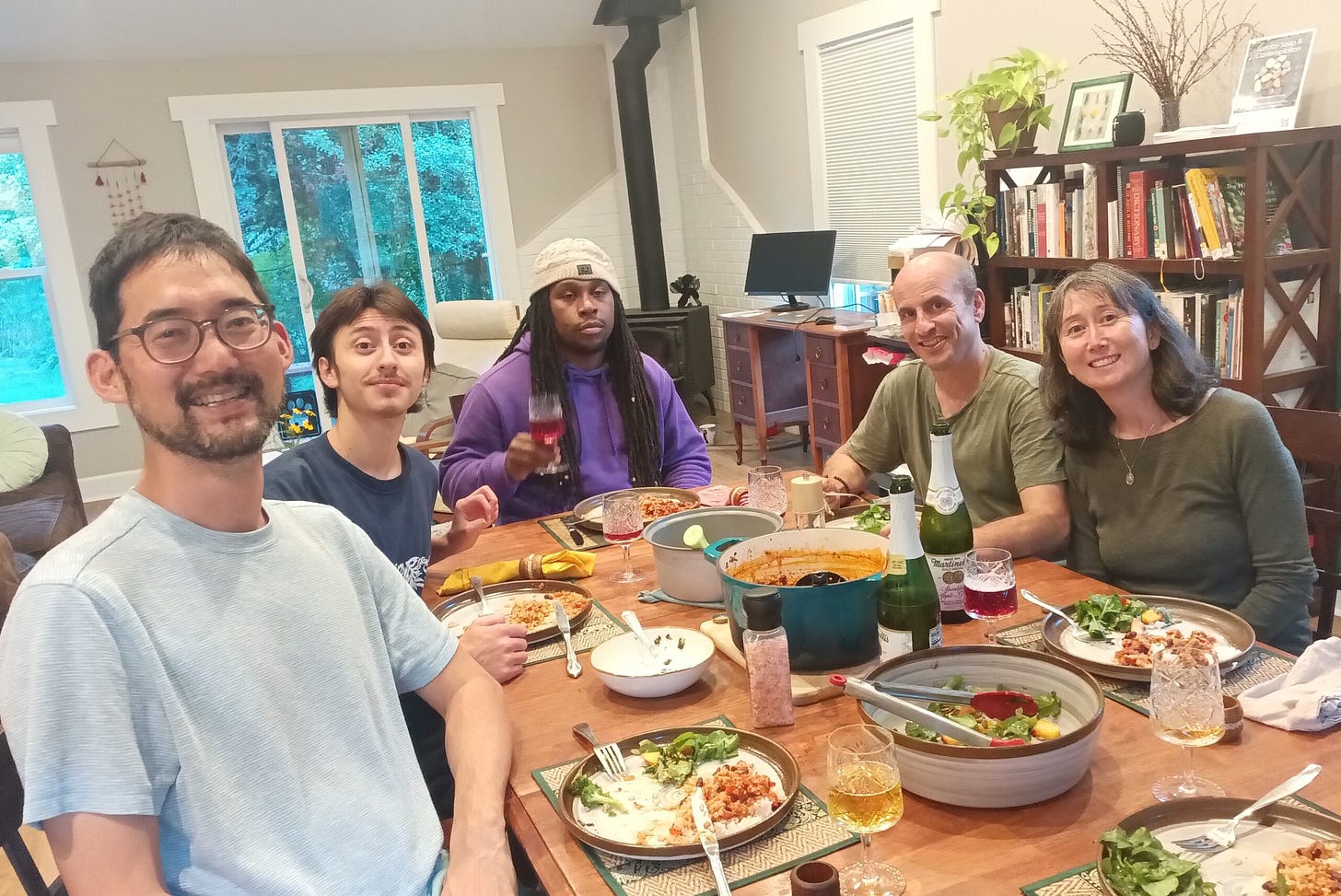

‘Slowly, We Become Community’: Julian Washio-Collette reflects on how community comes together at Dandelion House, providing their young guests with the support he lacked when his mother made him leave home at age seventeen.

Two Brothers, Two Forms of Personalism: Fumi Tosu reflects on his close relationship with his younger brother, who works for the World Food Programme, finding ways to bring his own brand of personalism to a large U.N. agency.

Celebrating Holy Families at St. Bakhita CW: Anne Haines shares a story of found family in the pews of the parish next to St. Bakhita Catholic Worker.

The Personalist Program of Peter Maurin: Finally, we reprint the May 1965 column in which Dorothy Day outlined Peter Maurin’s “program.” The essay includes several anecdotes from Peter’s life interwoven with his principal teachings.

Dandelion House is a small Catholic Worker community in Portland, Oregon, named for the feisty springtime flower. Dedicated to hospitality, justice, and solidarity, they offer temporary housing to individuals and families in need, serve a home-cooked meal to over 100 unhoused neighbors, and host regular gatherings that foster connection through prayer, storytelling, and shared meals. They’re looking for live-in community members, too.

St. Bakhita Catholic Worker, located in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, provides shelter and support to women wishing to escape sex trafficking. We profiled the community this past summer.

If you like these stories, consider signing up for the communities’ newsletters!

—Jerry

‘Slowly, We Become Community’

by Julian Washio-Collette

Originally published as “What Home Is” at the Dandelion House website.

“Slowly, we become community. It doesn’t happen overnight, but over the weeks and months that our guests live with us, we learn to trust and rely on one another.”

One night past midnight shortly before my seventeenth birthday, at my mother’s command, I hurriedly threw whatever I could of my meager belongings into a large plastic garbage bag, slung it over my shoulder, and headed out the front door. This was the last time I would call that house “home.” I walked through the still, quiet darkness of suburban neighborhoods until I reached the house of a friend, where I deposited the bag beneath an awning for safe keeping. Then I collapsed into a brief, fitful sleep on a nearby lawn.

Thus was I abruptly initiated into the world of adult independence, for which I was woefully unprepared. While many of my peers readied themselves for college, I felt paralyzed by the impacts of the troubled family life I had left behind, and overwhelmed with the bewildering challenge of having to suddenly make a life for myself in the world. Most of all, I felt profoundly alone.

I am grateful that what we hope to offer to our young guests at Dandelion House are some of the things that I lacked. In their own words:

“Dandelion House is my home. I can come here and know that I am safe. You showed me what love is, and what home is.”

“What I like about Dandelion House is the community. In my household we didn’t eat dinner together or talk about life, so doing that here has opened up my horizons for how I want to lead my family when I choose to have one.”

“Everyone here is ridiculously nice. You don’t know what you’re going to get out in the world, but then you come home to Dandelion House and there is something consistent here, a consistent amount of care, a consistent amount of openness. This is healing childhood scars for me.”

At Dandelion House, we strive to be more than shelter and food but a real home and a safe, caring environment where people can find rest and healing and receive the unique, personal help that they need. Rebuilding begins with secure, stable relationships. Our guests live with us and share weekly meals as well as household chores. We support them in meeting their goals, whether that’s getting a driver’s license, earning a GED, paying off debts, opening a checking account and saving money, or getting into residential detox. Slowly, we become community. It doesn’t happen overnight, but over the weeks and months that our guests live with us, we learn to trust and rely on one another.

The Christmas story recounts a migrant family looking for shelter in Bethlehem. The innkeeper, out of rooms but not out of compassion, makes a place for them in the stable, where the baby Jesus is born. And this story continues to unfold in our day and in our own lives. As Catholic Worker founder Dorothy Day reflects, we are not “born two thousand years too late to give room to Christ. Nor will those who live at the end of the world have been born too late. Christ is always with us, always asking for room in our hearts.” We are immensely grateful to you—our friends, volunteers, and supporters—for enabling us to more abundantly open our hearts and our home to Christ who comes to us in the form of those who need our help.

May you be richly blessed this Christmas season, and may the peace of Christ reign in our hearts and heal our broken world.

Two Brothers, Two Forms of Personalism

by Fumi Tosu

Originally published as “Personalism in Action” at the Dandelion House website.

“There are days I yearn to make a difference at scale, the way my brother does, eliminating malnutrition, hunger, and poverty for thousands. Yet, I know my calling is different.”

My younger brother, Fumitsugu, who, confusingly, also goes by Fumi, is one of my heroes. He is an amazing father to two beautiful children (plus two beagles), still a triathlete in his mid-forties, and works long hours to end hunger in the world. The U.N. agency where he has worked for over a decade, the World Food Programme, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2020 for its efforts to combat hunger, promote peace in conflict-affected areas, and prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict. WFP delivers emergency food aid to the millions around the world facing severe hunger, often as a result of conflict. They also invest in myriad local initiatives to bolster regional food production and resilience.

The World Food Programme is one of those agencies that restores my faith in institutions. They work to provide immediate relief to those in need, while also tackling the larger, systemic causes of hunger.

I often think about our two lives — my brother’s and mine. As children, I wonder how much he felt over-shadowed by his older brother, as our teachers and coaches called him “Little Fumi” or “Fumi #2.” We share much: the same family, the same roots in Tokyo, the same school whose motto was to educate leaders “prepared for global responsibility,” even the same name. We were both drawn to careers working for a better world — him at the United Nations, me at the Catholic Worker. Yet our daily lives could not be more different — he works in an office, supervising dozens of employees and managing projects, while I work in the kitchen, chopping dozens of onions and managing slow cookers.

There are days I yearn to make a difference at scale, the way my brother does, eliminating malnutrition, hunger, and poverty for thousands. Yet, I know my calling is different. My calling is to work with the two, three or four individuals we can house at one time at Dandelion House, or the 120 to 160 people who come to us for a hot meal on Fridays. It’s to grow vegetables in a few garden beds, to keep a hive of bees in the backyard, to learn from and care for the various beings in our local watershed.

This is what Catholic Worker co-founders Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin called “Personalism.” It’s the idea that, because every single person has dignity beyond measure, we are called to personally care for our immediate neighbors. My friend and colleague Matt Harper from the Los Angeles Catholic Worker quotes our friend Larry Holben in an excellent article in the Catholic Agitator: “We do not need to wait for systems, governments, social structures, or circumstances to change and make it easier for us, or to bear the burden of the responsibility…. We can make a conscious, deliberate choice to bring the kingdom of God into the one particular portion of history which is ours and ours alone to touch.” (Read the full article in the December 2023 Agitator at lacatholicworker.org.)

Of course, we all do this in one way or another, whether we work for the Catholic Worker or the United Nations. In May, I had the chance to visit my brother in Cambodia, where he currently works. As I spoke with his colleagues it was clear to me why he was so successful at his job — it was his gentle personalism, the care with which he listened and related to others, whether colleagues, community partners, or the beneficiaries of WFP’s myriad programs. As we visited an elementary school where WFP had recently built a new cafeteria, my brother, usually a towering figure at 6’3”, became Little Fumi again, conversing in broken Khmer on bended knee with the school children over breakfast. Listening, caring, loving — that was the face of the United Nations for the children at Smet Primary School in Kampong Chnang Province, Cambodia, that morning.

There is work that needs to be done at scale. And always, we must demand that systems and governments work for the advancement of social justice, since, as Matt writes in his article, “for what other purpose do these entities exist?” At the same time, amidst the pressures of a turbulent world, we invite you to seek your center in “the one particular portion of history” which is yours to touch.

Celebrating Holy Families at St. Bakhita CW

by Anne Haines

Originally published as “We are Family” on the Bakhita House website.

“The love I feel for the women who sat with me caused me great worry. How did they feel about all this family talk when some of their experiences are quite difficult?”

Family. Few words evoke such a vast gamut of emotions. Some of them filled with joy, others wrought with immense challenge. You can imagine that this is particularly nuanced when it comes to women survivors of sexual exploitation. That is why on Sunday, which is traditionally the Feast of the Holy Family in the Catholic Church , I acutely felt this reality. Both for midnight Christmas Mass, and for Mass on Sunday, three community members asked if they could attend with me. I was somewhat taken aback, in a good way. I felt joy to have their company in the pew.

Now the faith community next door, at St. Martin de Porres Catholic Parish, could not be more welcoming. They greet everyone with a joyful face and invite everyone to introduce themselves. The sign of peace is an extended banquet of hugs, smiles and warm wishes. But it was the introductory message, delivered by a dear friend and a member of the laity, that had a particularly powerful effect on me. The message started with a homage to Mary, Joseph and Jesus. The Holy Family. It celebrated this beautiful trio and harkened us to celebrate our families, past and present, that reflect their many positive and exemplary attributes.

However, in my pew, and I am sure throughout the Church, there sat many members of families that don’t exactly reflect this image. On this day I was particularly aware of this. The love I feel for the women who sat with me caused me great worry. How did they feel about all this family talk when some of their experiences are quite difficult?

But then it happened, my beautiful friend began to call out the many iterations of family. I heard it, “We welcome the beautiful Bakhita family who are our beloved neighbors.” I could viscerally feel the tension dissipate from my body and my heart truly rejoiced. Hallelujah, God is with us! We are family.

We wish you and your many kinds of family a Merry Christmas and a beautiful 2025! We do consider you members of our extended family and we appreciate, love and pray for you as such. This is how we will change the world!

The Personalist Program of Peter Maurin

by Dorothy Day

Originally published as “Peter Maurin, Personalist,” in the May 1965 issue of The Catholic Worker.

“Peter Maurin’s teaching was that just as each one of us is responsible for the ills of the world, so too each one of us has freedom to choose to work in “the little way” for our brother.”

We are usually driving back and forth to the farm at Tivoli, but on the few occasions when I have taken the train from Grand Central station, I have enjoyed the view from the river side, and been oppressed by one aspect of the view from the land side. That is, the ugly habit of people to use as dumps the back yards of their houses as well as the swampy places and creek beds of the little streams flowing into the Hudson. In Yonkers, especially, there are some rows of houses that evidently front the street and where the front yards are probably well cared for. But garbage and trash have been thrown down the cliff side that leads to the railroad tracks and Hudson River, so that it hurts each time one sees it.

Suddenly, I thought one day of one of the jobs Peter Maurin had undertaken on the first farm we owned at Easton, Pennsylvania. It was a job which illustrated many of his ideas but also his love of beauty, his sense of the fitness of things. It also illustrated what he used to call his philosophy of work.

There were two farms, actually, at Easton, the upper and lower farm, and it was on the lower farm that most of us were housed and where we had our retreats every summer. There was one old house, two large barns, one of which we used for the animals, and the other of which we converted into chapel, meeting room, dormitories, and at the lower level, a long kitchen and dining room. The entire barn was built on a hillside so that on the road level the entrance was into the chapel and dormitories. It was below that, on a much lower level, that we had converted cowstalls into a long concrete floored room which made up the kitchen in one corner, and long dining room which could seat thirty or more guests. It was only later that we had electricity and running water in that kitchen. For several years we used lamplight and water from the spring house across the road.

At the very end of this large building, connected with it by one stone foundation wall, there was a foundation built up with field stone ceiling-high, which was overgrown with weeds when we first saw it that first summer, which was so hectic that we saw no further than that. We were too busy caring for the dozen children from Harlem and the numerous guests, most of whom were sick in one way or another.

But the winter disclosed the painful fact that this beautiful foundation, overlooking the fields below it and the Delaware River Valley far below that, was actually filled half way to the top with all the debris of years. The tenants of the farmhouse before us had used the foundation as a convenient dumping ground for garbage, tin cans, old machinery, discarded furniture, refrigerators, washing machines and other eyesores such as I complain of seeing from the windows of the train. (What to do with all this waste, all these old cars and machines, is one of the problems of the day.)

Peter Maurin surveyed this dump and, before we knew anything about his project, he was hard at work at it with wheelbarrow and pick and shovel. He had undertaken, with no assistance, to clean this Augean stable. Actually, we had no plans then, nor did we for several years, for utilizing the foundation and making an additional house on the property.

Fortunately, the ground sloped so steeply down back of the barns that Peter’s engineering project was feasible. By dumping the refuse over the back and covering it with fill (another laborious job since he had to wheel loads of this heavy clay earth from the wooded hillside further down the road) he widened the foot path in back of the barn so that it became a narrow road around the back of the barn and, in fact, a little terrace where it was possible to sit and survey the long sloping valley below, a scene of incredible beauty, since we were high on what was called Mammy Morgan’s Mountain, overlooking the conjunction of the Lehigh and Delaware Rivers.

I do not know how long this great task took Peter Maurin, the sturdy French peasant with the broad shoulders, the strong hands which were the hands of the scholar, more used to handling books than the shovel. He had taught in the Christian Brothers’ schools in France in his youth and though peasant-born, had received a good education.

Philosophy of Work

I write this account of a piece of work, which I remembered only because the sight of the dumps from the train window which had flashed by in one short instant, had brought it suddenly to my mind so that I knew I should write about Peter in connection with it. It started a long train of thought which had to do with many of our problems today and Peter’s solutions. I will try in this short space, and no matter how inadequately, to summarize them, although each of the points he used to make could be expanded into a day-long discussion.

First of all, it must be emphasized that Peter Maurin was a deeply religious man. He never missed daily Mass, and many a time I saw him sitting quietly in the church before or after Mass. When he lived on Fifteenth Street he walked to St. Francis of Assisi noon-day Mass. When we moved to Mott Street, where he lived for fifteen years, he walked to St. Andrew’s near City Hall to go to the noon-day Mass there. He never rushed, but walked in most leisurely fashion, his hands clasped behind his back, ruminating no doubt, paying little attention to shops (except for bookshops) or to passersby or even to traffic.

He read and studied a great deal, delighting to find new authors who could contribute to what he called the new synthesis of Cult, Culture and Cultivation. Cult came first, emphasizing the primacy of the spiritual. (Poor proof reading overlooked the error, “privacy of the spiritual,” in last month’s issue.) He never talked personally of his own spiritual life, but recommended to us such writings as Karl Adams’s Spirit of Catholicism; Pius XI’s 1927 Encyclical on St. Francis of Assisi and the Rule of St. Benedict.

He recommended the writings of the saints, as they had to do with their practical lives, what their faith led them to be and do. When Ade Bethune came to us as a high-school girl with drawings of the saints, Peter urged her to picture the saints as workers, and she drew pictures of Our Lady feeding the chickens, sweeping a room, caring for a host of children; not someone to be worshipped, but to be followed. Ade and others who followed her in this tradition (Carl Paulson in his stained glass) pictured St. Benedict planting a field, St. Peter pulling in his nets, St. Martin de Porres feeding a sick man.

Work, according to Peter was as necessary to man as bread, and he placed great importance on physical work. I can remember a discussion he had with the great scholar Dom Virgil Michel, who was the pioneer of the liturgical movement in this country.

“St. Benedict emphasized manual labor, as well as intellectual,” Peter said. “Man needs to work with his hands. He needs to work by the sweat of his brow, for bodily health’s sake. We would have far less nervous breakdowns if men worked with their hands more, instead of just their heads.”

As a result of Peter’s emphasis we were called romantic agrarians and, without paying attention to Peter’s more profound vision, national leaders in the field of social justice and civil rights insisted on misunderstanding our whole message, which was one emphasizing the necessity of farming communes, rather than individual family farms, cooperative effort rather than the isolated and hopeless struggling with the problem of the land and earning a living from it. He cited the cooperative effort of Fr. Jimmy Tompkins and Father Coady of Nova Scotia, and the cooperative teaching of the Extension department of St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, where there is still active leadership in the cooperative movement. He was deeply interested in the kibbutzim of Israel.

Work, Not Wages

A philosophy of work meant an abolition of the wage system. An explanation of that phrase would mean another long article. It would mean, “Work, not wages,” a slogan which Peter delighted in, as he did all slogans which made man think. (There is a new slogan now, “Wages, not work.”)

It is to be remembered that the first plank in Peter Maurin’s program for the world was “clarification of thought.” I remember John Cogley’s comment one time that all slogans, all such phrases, became clichés in time, and Peter, the Frenchman, tried to keep up with the slang phrases of the day and to probe to the root of them as to what they meant, what they signified at the time. I remember one of his essays ending in a long list of such slang phrases, the last of which was, “So’s your old man!” capped by the sardonic, “So what!”

Once, when I looked around our crowded house of hospitality and asked Peter if this is what he meant when he talked about houses of hospitality where the works of mercy could be performed at a personal sacrifice, by practicing voluntary poverty, which meant in turn stripping one’s self of the “old man” and putting on the “new,” which meant Christ, so that we could be other Christs to our brothers, in whom we were also to see Christ, Peter sighed and said, “It arouses the conscience.”

Yes, it has aroused the conscience to the extent that some of our readers, (now we are printing 80,000 copies of the Catholic Worker each month), have supported us in this work to which we in turn have given our labor for the past thirty-two years, but it indeed is a precarious existence and it demands a great exercise of our faith to remain cheerful and confident in it.

Right now, Ed Forand, who pays the bills for farm and city House of Hospitality, and Walter Kerell, who gets the mail and opens it hopefully each morning, are talking of the summer ahead and the bills piling up, and reproaching me for being late in sending out what was supposed to be an appeal. “And you did not really make an appeal,” they said.

I find they are right. This morning’s mail brings me a letter which begins, “Your form letter of a month or so back did not come right our and ask for money; so I sent none. Today I got around to reading the April Catholic Worker with its On Pilgrimage…Here is $5 from my $60 a month social security.” Our correspondent was an itinerant linotype operator and is a member of the United Church of Christ and the rest of his letter, his statement of his beliefs, is most interesting and we will print part of it later.

It is good we live still today, sixteen years after Peter’s death, in such precarity that sudden large bills frighten us – such as a tremendous plumbing bill for the dingy old loft building which is part of St. Joseph’s House of Hospitality on Chrystie Street; and an electric bill at Tivoli where we need new poles to convey electricity to our house of hospitality on the land, which is pretty much what our farm amounts to.

But Peter’s faith was invincible. God would supply our needs, provided we were generous with our work and sacrifice. He had never failed any of the saints, and we were all called to be saints, as St. Paul said. Again he would call our attention to those who should be our leaders and teachers, the saints.

Also, such a crisis, he would point out hopefully, could lead us to a truer practice of poverty so that we would set a better example to the destitute. “Eat what you raise, and raise what you eat,” was another slogan. Which meant, of course, that you would eat apples and tomatoes in this New York region, instead of oranges and grapefruit. You would have wine, but not tobacco! You would have honey, but not cane sugar. All to which means work, and the knowledge of how to work in the fields.

And as for electricity! The old mansion on the Tivoli farm has cisterns all around it (which we cleaned out last summer during the drought) and newly painted metal roofs, and if it rained (the drought is three years old now and farmers are talking of seeding the clouds, if there were any clouds to seed, to produce rain) we would have water in the cisterns and a hand pump would give us water even if the electric pump of the artesian well failed us. And we could build an ice house and cut ice from the river to conserve our food and find other ways to preserve it also, though raising roots would be better – I can hear him now with all the solutions to a problem of survival.

In addition to a philosophy of work, and a philosophy of poverty which would intensify the need to work, and provide work for others who are without work in time of crisis, not to speak of the health attendant upon such efforts — there was also the study of man’s freedom and this seemed to be the foundation of all Peter’s thought in that time of dictatorships, when a Hitler, a Stalin, a Mussolini dominated men’s minds and bodies. Man was created with freedom to choose to love God or not to love him, to serve or not to serve, according to divinely inspired Scriptures. Even this statement presupposes faith. He is made in the image and likeness of God and his most precious prerogative is his freedom. It is essentially a religious concept. It is in that he most resembles God.

Man, knowing his own personal responsibility, should not say, “They don’t do this or they don’t do that.” Whether it was Church or State that was being criticized and judged. Instead, Peter Maurin went back, as Cardinal Newman did before him, and studied the teachings of the Fathers of the Church. “Except,” said the Abbot Allois, “a man shall say in his heart, I alone and God are in this world, he shall not find peace.”

These are extreme times when man feels helpless against the forces of the State in the problems of poverty and the problems of war, the weapons for which are being forged to a great extent by the fearful genius of our own country. “With our neighbor,” St. Anthony of the desert said, “is life and death,” and we feel a fearful sense of our helplessness as an individual.

Peter Maurin’s teaching was that just as each one of us is responsible for the ills of the world, so too each one of us has freedom to choose to work in “the little way” for our brother. It may seem to take heroic sanctity to do so go against the world, but God’s grace is sufficient, He will provide the means, will show the way if we ask Him. And the Way, of course, is Christ Himself. To follow Him.

About us. Roundtable covers the Catholic Worker Movement. This week’s Roundtable was produced by Jerry Windley-Daoust and Renée Roden. Art by Monica Welch at DovetailInk. Roundtable is an independent publication not associated with the New York Catholic Worker or The Catholic Worker newspaper. Send inquiries to roundtable@catholicworker.org.

Subscription management. Add CW Reads, our long-read edition, by managing your subscription here. Need to unsubscribe? Use the link at the bottom of this email. Need to cancel your paid subscription? Find out how here. Gift subscriptions can be purchased here.

Paid subscriptions. Paid subscriptions are entirely optional; free subscribers receive all the benefits that paid subscribers receive. Paid subscriptions fund our work and cover operating expenses. If you find Substack’s prompts to upgrade to a paid subscription annoying, email roundtable@catholicworker.org and we will manually upgrade you to a comp subscription.