The Hartford CW Mentors Neighborhood Kids & Builds the Beloved Community

Also in this issue: Documenting extrajudicial killings in the Philippines; "radical" Catholics; London CW protest; Cherith Brook celebration; and badass female saints.

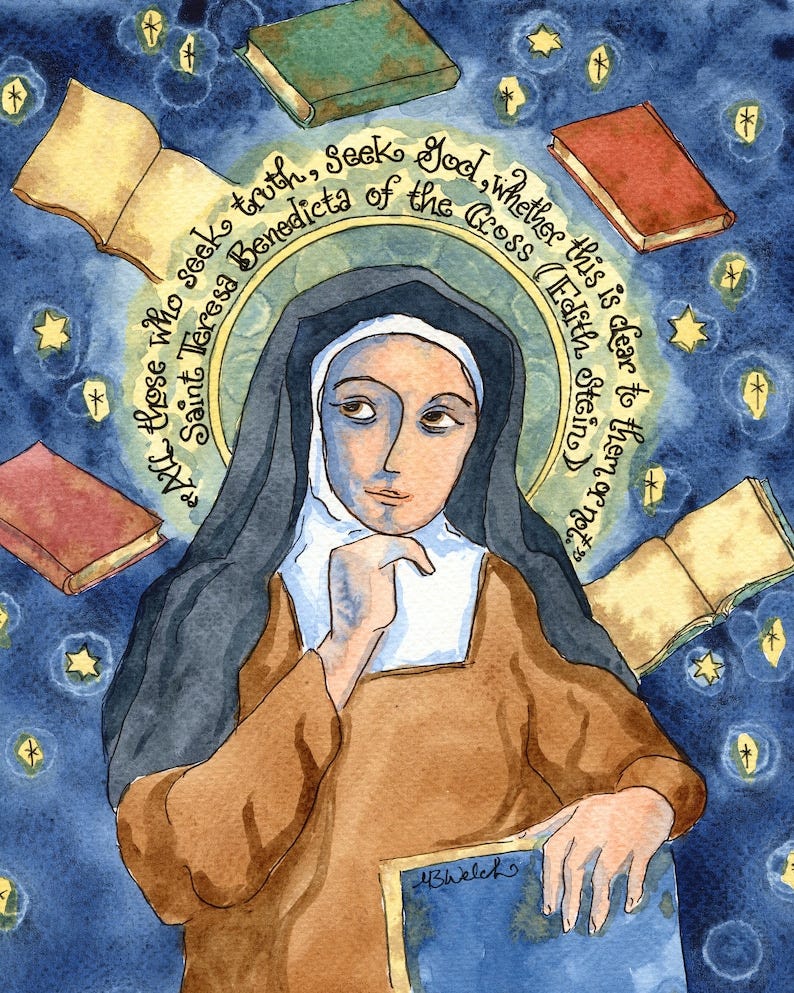

Dorothy Day and Edith Stein: Badass Saints

“Why female saints?”

This is usually the first question I’m asked when I inform someone of my area of study in theology. It makes sense: I study a seemingly small subsect of seemingly dead people. Even worse, society tends to paint “saintly” women as passive or weak.

But the truth is, female saints are badass.

They were incredibly strong women. Despite the injustices they faced on the basis of sex, they persevered: They instructed popes, reformed religious orders, and improved social structures.

Servant of God Dorothy Day, of course, is a great example of this. She called out the injustices of the world and the hypocrisy of the Church. For her, this was a fundamental part of being a Christian and loving the Church.

During Day’s lifetime lived another badass woman who similarly shepherded the Church: St. Edith Stein. As a Jewish Catholic convert living during World Wars I and II, Stein faced many injustices for her identity, but this didn’t stop her.

During the Holocaust, Stein wrote a letter to the pope urging him to speak out against the persecution of Jews, writing that “it is harmful to the image of the Church worldwide if this silence is prolonged further… Is not this idolatry of the race and of state power stark heresy? Is not this war of extermination against Jewish blood an outrage against the sacred humanity of our Saviour, of the Holy Virgin and of the apostles?”

Stein was the first European woman to earn her Ph.D. in philosophy, and she did so with highest honors. Her philosophy is marked by its personalism, a core value of the Catholic Worker. Her care for the human person was not just a theoretical belief, but a lived practice. As she was led to Auschwitz, she said to her sister, “Come, we are going for our people.” In the moments leading up to her death, Stein cared for those around her, especially the children orphaned by the genocide.

Stein and Day, like many other female saints, were rather defiant women. Out of love for the Church and her people, they put themselves at risk to nudge the Church in the right direction. This is what makes them so badass, fascinating, and worthy of study.

Stein’s feast day was celebrated this past Friday, August 9. She shares this feast day with Blessed Franz Jägerstätter, another Catholic martyr of the Holocaust — both were killed on the same day, one year apart.

Jägerstätter, too, spoke out against the injustices of the war, ultimately being killed for his refusal to join the Nazis. This newsletter concludes with some words written about Blessed Franz Jägerstätter in August 2001.

—Scarlett

Scarlett Rose Ford is a graduate student at Harvard Divinity School. She is interning with CatholicWorker.org this summer.

FEATURED

The Hartford CW Mentors Neighborhood Youth

The Hartford Catholic Worker is one of only a handful of Catholic Worker communities to focus their work almost exclusively on children and youth. Unlike other youth programs, they work with the children and teens who live right in their neighborhood, establishing deep, long-term relationships. Some of those relationships have spanned decades, with kids who first stopped by the “Green House” or “Purple House” at age five continuing to spend time there decades later, often mentoring a new generation of youth.

Theo Kayser and Lydia Wong interviewed Jackie Allen-Doucot for their Coffee with Catholic Workers podcast back in early spring. The episode aired in May; the transcript is finally available at CatholicWorker.org.

Jackie and her husband, Chris Allen-Doucat, met one another while working with the Sts. Francis & Thérèse Catholic Worker in Worcester, Massachusetts. Eventually, friends encouraged them to start a new Catholic Worker in Jackie’s hometown, Hartford. The couple spent a year praying and studying with a group of 10 people, including Brian Kavanagh, who eventually joined the live-in community with them. Along the way, they had their first child and managed to purchase a $150,000 house for $10,000.

It was “super hard” in the beginning, she said, “but every step we took was, we sort of realized that, okay, the Holy Spirit must want this to happen because good things would happen.”

At first, they opened up their home to unhoused people. in the early years, they ran a food pantry and a furniture pantry, too, but the neighborhood kids kept coming around. Eventually, they started an after-school mentoring program for those kids. Their work with the neighborhood youth expanded after one of the kids they had known from a young age was shot and killed.

“That really made us reevaluate how we were doing our work,” Allen-Doucot said. “And the biggest need seemed to us (to be) to hold onto kids. All teenagers…(need) connection and support and community and families.”

That’s when they purchased their second house, turning the backyard into a huge playground and a full basketball court. “And we started to kind of pay kids to be counselors and that kept the older kids in,” she said, “and that evolved into a beautiful thing where the older kids mentor the younger kids.”

They began partnering with the University of Connecticut’s Husky Sport Program, where athletes and students establish mentoring relationships with neighborhood children, teaching them about sports and nutrition.

“We always are real clear with (outside volunteers) that…you're not there to give and the poor children are there to take,” Allen-Doucat said. “We break down why poverty and institutional racism exist together and what the need is to make right relationships and to make amends for what white supremacy has done to our neighborhoods and our communities.” The neighborhood is almost entirely Black, she said.

“We try to bring people in to break down that apartheid thing, to make the poor not be an anonymous thing, but people, you know, who are in the states they're in because of the way we live—the way we’re ready to pay $114 billion over the next 10 years for 14 new Trident submarines….

“We teach people about (how) Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker is not just about doing good. It's about…addressing the causes that make it necessary to have charity.”

They teach the neighborhood kids conflict resolution skills, and co-sponsor a summer peace camp with their sister organization.

“We get kids out of the ghetto and out into the country and they swim every day and run around the woods at night playing manhunt. And we do conflict resolution with them; we have this thing called the Hip Steps. And after a while, the bigger kids teach the younger kids, and it’s something that we really believe not just benefits our community, but these kids take it into their schools and their jobs and their work.”

It can be tough, exhausting work, she told Lydia and Theo. Kids who grow up in poverty and around addiction don’t always have the best coping skills, which can present problems. The Allen-Doucats’ two boys grew up in the Worker, which was also very challenging, she said. And now, as the founding members age, they are facing an uncertain future both for themselves and the community.

But all the work and hardship are worth it, she said, because it is a glimpse of the Beloved Community. “I think our community is really awesome because we do a great job of (building that community). When you look around our house on a Saturday, you see old and young, you see gay and straight, you see neurodivergent and genius people, and you see black, white, brown.

“We have so much variety and we tell people, that's what the kingdom of God looks like, and when you’re in communities that don’t have that, you are the ones that are needy, you are the ones that are living with a loss, and you need to be made whole.”

You can read a transcript of the full conversation or listen to the podcast at CatholicWorker.org.

What’s Your Passion?

What Does It Mean to be a “Radical” Catholic?

In the second part of the introduction to Colin Miller’s new book, We Are Only Saved Together: Living the Revolutionary Vision of Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement, Miller argues that the Catholic Worker is not “liberal” or “conservative,” but simply “radical”—in the sense of getting to the root of the Gospel.

The book, released August 4 by Ave Maria Press, is not a history of the Catholic Worker Movement, “but an introduction to and application of its way of life to our world”—an invitation for ordinary Christians to take up its principles in order to live their faith more “radically.” Here’s an excerpt:

Maurin’s call to be radical Catholics is what the Second Vatican Council called the “universal call to holiness.” Sometimes today that is dumbed down to mean that just being ordinary is being holy, but it’s actually the opposite of that. This call to holiness means that the example of the saints, the tough demands of the Gospel, the invitation to be utterly transformed and give everything for Christ—and indeed receive everything from him—are meant not just for a select few Christians, but for all of us. The Catholic Worker prophetically anticipated this universal call and was part of a chorus of voices that brought it forth.

The movement did more than that too. It articulated a particular shape, a specific set of practices, a way of life, that would be that holiness embodied in our world today. For the real question for us is not whether we should be holy—of course we should. The real question is, What does the universal call to holiness look like in America today? What should I do to be holy?

As clearly now as almost a hundred years ago, Maurin and Day’s answer points us back to the root: small communities of common worship, lay leadership, local living, hospitality, simplicity or even voluntary poverty, friendship with the poor, and a serious, deep Catholic analysis of our culture. While this is not the only example of faithful Catholic life out there (and I won’t be suggesting that we all must become Catholic Workers ourselves in any formal sense), the movement is instructive for all of us because at its best it is simply the practice of traditional Catholicism given fresh expression for our own culture.

In other words, our world being what it is, and the Gospel being what it is, something like the Catholic Worker vision is increasingly prophetic for those of us looking for an alternative to the status quo. While utterly faithful to the Church and its tradition, it is in some ways a new sort of holiness, necessary to meet the demands and complexities of a challenging new age. Or rather, as Maurin might say, it’s a holiness so old it looks like it’s new.

. . . .

This book is a call to an adventure. It’s not for the spiritual elite; it’s for everyone, because the Gospel is for everyone. And because it’s the Gospel, the Lord knows that none of us will take it on all at once. Adventures are journeys, after all. They are baby steps for all of us, and no one is expecting perfection.

For while Christians are idealists in the best sense of the word, part of the genius of the Catholic Worker is its absolute clarity that there has to be a deep humor and gentleness suffusing everything we do. Laughter and silly stories and failure are the norm. “Judge not” should always be on everyone’s lips. We have to live and preach and pray hard because Jesus is real, and we have to be merciful and jovial and infinitely indulgent with our neighbors and ourselves because, you might say, the point of the counsels of perfection is that we don’t keep them perfectly.

But the Catholic Worker is an adventure just the same. You will come back changed, if you make it back at all. Like the Gospel, this adventure is not just an adjustment of something that we need a little work on, or a mere change in perspective. It’s a total revolution.

Read the entire piece at CatholicWorker.org.

THE ROUNDUP

Magnificat, the paper of the Nazareth House Catholic Worker in Manila, Philippines, spotlighted the story of one bereaved mother’s horrific story of witnessing the dehumanizing extrajudicial killings in Manila and losing her son in the War on Drugs, which former president Rodrigo Duterte waged in the Philippines from 2016-2022. Duterte is currently under investigation by the International Criminal Court for War Crimes. 30,000 people are estimated to have been slain in the first half of Duterte’s term. Read the story in Tagalog and English in Magnificat.

The Little Platte Catholic Worker Farm’s Allyson Winter and Lincoln Morris-Winter were profiled in the Dubuque, Iowa, Telegraph-Herald on Friday. “Being a Catholic Worker Farm is about listening to the land, being good caretakers of the land and working to restore our and others’ relationships to the land. In doing this work, we’re responding to God’s calling in our lives to tend to the most vulnerable and to nurture the sacredness of life,” Winter told the paper. The family will relocate this fall to the Little Platte Catholic Worker Farm in Platteville, Wisconsin. There, they will focus on land-based community life, regenerative agriculture, ecological rewilding, spiritual retreats, educational programming and land-based crafts and art.

The London Catholic Worker was among 10,000 people who marched for peace in the Holy Land on August 3, according to Independent Catholic News. The march was peaceful, with only four arrests; marchers called for an immediate ceasefire.

The Maurin Academy hosted the first of the “Harry Murray Sessions,” featuring Harry Murray, a professor emeritus in sociology at Nazareth College and a Worker emeritus from Unity Kitchen in Syracuse, NY and St. Joseph House of Hospitality in Rochester, NY. Murray spoke about Jacques Derrida’s treatises on hospitality, from his context as a Frenchman hosting Algerian refugees in defiance of the law. He contrasted that with Dorothy Day’s reflections on hospitality, and he peppered his talk with many stories of hospitality from “the trenches”—the fires, fights, and moments of grace when Catholic Workers have tried to practice what Derrida called “unconditional hospitality” and believed impossible—but Dorothy practiced. The recording of the talk will be available on their website.

Casa Maria Catholic Worker (Milwaukee) hosted a Lanterns for Peace event on Friday, August 9, remembering the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki 79 years ago. People gathered for refreshments and made Japanese lanterns and origami peace cranes. This was followed by a commemorative program and procession.

The latest issue of The Illuminator features a profile of “a major mover and shaker in the Catholic Worker art world, the inimitable Willa Bickham.” Although she is based in Baltimore’s Viva House, Bickham’s art is showcased in many Catholic Worker houses. She recounted for Becky McIntyre and Sarah Fuller the days of the Civil Rights movement and Vietnam War protests: “We made a lot of signs and banners to march with in Baltimore, and T-shirts. We had to do all the T-shirts. All of these things take community.” Read the entire issue here.

A celebration was held at Cherith Brook Catholic Worker (Kansas City, Missouri) on Thursday evening to celebrate the completion of the renovation of its storefront building on 12th Street and to honor founders Eric and Jodi Garbison, who are stepping back from their leadership roles. See a photo here.

CALENDAR

August 22 | St. Francis Catholic Worker, Chicago, Illinois

St. Francis House Roundtable Discussion

August 27 | St. Louis Catholic Worker, St. Louis, Missouri

Multi-Faith Prayer Gathering

September 6-7 | Chicago, Illinois

Peter Maurin Conference

September 12-15 | Sugar Creek, Iowa

Midwest Catholic Worker Gathering

October 4-6 | St. Francis Catholic Worker, Chicago, Illinois

Catholic Worker National Gathering

A FEW GOOD WORDS

“Do This In Memory Of Me,” The Catholic Worker, August/September 2001

By Michael Patrick Griffin, CSC

Franz Jägerstätter—martyred by beheading on August 9, 1943 for refusing to serve the Nazi regime—must not be forgotten. It is not merely that he saw the dangers of secular allegiance at a time when others did not. It is not merely that he spoke truth to power at a time when many Church leaders could not. More than this, Franz Jagerstatter believed the Gospel so deeply that his life cries out to us like a mantra, “Jesus, Jesus, remember Jesus.” So what is to be done with this holy man? I say: We hold him up as an icon of Christ; we share his story; we draw strength from him. In short, we make him a saint. And we do this not because he needs our vindication; rather, we desperately need him.

I was reminded recently just why I think the people of God today need Franz. As part of my formation with other Holy Cross seminarians here at Notre Dame, we were reading a well-known article by Cardinal Avery Dulles (from America, 20 June, 1998). He suggested that orthodoxy and the defense of the magisterium must stand front and center in counter-cultural discipleship today. After noting that “the Church has been equipped by God with hierarchical structures,” he claims that “faith, as a way to salvation, involves submission to the authoritative teaching that comes from God through the Church.”

Cardinal Dulles rightly points out that our culture so lionizes “thinking for ourselves” that it dismisses concepts like Church teaching. Indeed, many young people today agree with him and are clamoring for a more obedient Catholicism. And yet, this push for orthodoxy and “right belief’ can pose dangers to our Catholic tradition. When separated from “right practice,” Church teachings become the object of our faith. Further, defining the good Catholic solely by where one stands relative to the hierarchy ignores the social order. This has yielded a sad void in what Thomas Merton once called “the Church’s mission of protest and prophecy.” In the name of traditional faith, we are at risk of losing an ancient claim of the tradition: Christian faith is political.

It is precisely on the relationship between belief and practice, between obeying the voice of the Church and being a voice to the Church, between faith and politics, that the life of Franz Jägerstätter registers a powerful witness…If those of us committed to the ideals of the Catholic Worker wish to be a voice in the Church, this is a discussion that needs to happen.

… Franz Jagerstatter’s roots in the Church and his fidelity to its tradition challenge all Catholics working for social change today. Hope for success in the struggle against entrenched injustice cannot be pinned on the social movements of the day, on the aims and means of the left. They may offer progress on materialist terrain, but are less steeped in a revolution of the heart that places the ways of God—revealed in Jesus—at the center of social transformation. Indeed, the goals of secular activism are simply not ambitious enough for those seeking the Kingdom of God.

But, the story of Franz Jagerstatter lights a different way. He was compelled not by ideology, but by the hope of his Baptism, by the Easter faith of the Church that God—and not the mighty of this world—has the last word. Only because of this sure hope that “the power of God cannot be overcome” could he face the machinery of war and death and say: no to you, yes to God. In fact, the fruits of his life as a baptized “priest, prophet and king” hearken to the early Church. In that era, catechesis was not so focused on knowledge but was thoroughly moral and, in fact, calls into the question the modern distinction between beliefs and practices.

Roundtable covers the Catholic Worker Movement. This week’s Roundtable was produced by Jerry Windley-Daoust, Renée Roden, Joan Bromberek, Monica Welch, and Scarlett Ford.

Roundtable is an independent publication not associated with the New York Catholic Worker or The Catholic Worker newspaper. Send inquiries to roundtable@catholicworker.org.

https://youtu.be/HaU8wnT5IZs?si=ytKtAmoe54EMZ0Rh

Interview RFK Jr if possible