Who Will You Meet at the Catholic Worker?

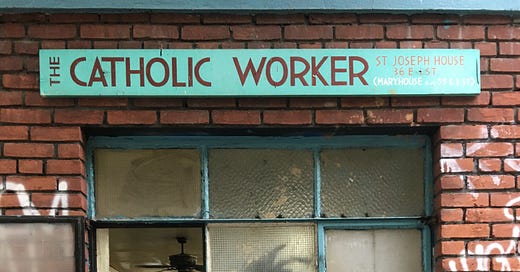

From "Do Not Neglect Hospitality": Harry Murray on who's who at St. Joseph's House of Hospitality in New York City.

We continue our serialization of a chapter from Harry Murray’s “Do Not Neglect Hospitality” with his observations about the different “types” of people who populate a Catholic Worker house.

You can read part one of Murray’s chapter on St. Joseph’s House in New York City here, part two here, and part three here.

Murray observes the tension between “personalism” and the commitment of each Catholic Worker to seeing each person as an entire person—their own history, personality, and dignity—and the ways in which the community sorts different people into roles or assesses their character.

I think the crux of his insight lies in this paragraph:

The emphasis among Workers is on personal history rather than type. Workers are expected to "know the guys." One need not know any theories of drug addiction. One should know that when Abe asks to use the bathroom, he is probably going to try to shoot up there. One need not know the difference between paranoia and schizophrenia. One should know that it is no problem if Harvey chooses to talk to the doorknob.

Catholic Workers, like any community, assess a person based on their actions—they seem friendly, they are cooperative, they’re pugnacious, they’re self-interested, they’re caring—and those actions shape their relationship with the community that lives in the house and the house that holds the community.

But these roles, as Murray writes, are up for negotiation: each Worker, guest, visitor, can carve out their own—personal—role in the community. And the community, which has a great tolerance, he writes, for ambiguity in the typifications, and a capacious acceptance for odd, idiosyncratic or even “crazy” behavior, has an elasticity to usher each Thou who comes through the door into something like belonging.

peace,

Renée

Grasping the Other as a “Thou”

From the Chapter, “The Flagship,” in “Do Not Neglect Hospitality” by Harry Murray

Typifications of People

Although a personalist approach to hospitality emphasizes treating the guest as a whole person, as a thou, it is impossible to conduct social relations without some sort of mental scheme of "types of persons" (Schutz 1967). It is inevitable, therefore, that even with the avowed purpose of treating others as pure thous, the Workers would develop schemes for typifying persons. As I will show, however, both the type of schemes used and the way they are used differ from those of bureaucratic social-service agencies in a way that facilitates the grasping of the other as a thou.

An important distinction to make at the outset is that the typifications of people at the house take the form of ideal types rather than categories. By this I mean that idealized pictures of various types of persons are created, but real persons are not expected to correspond to any one type. In an ideal-typical scheme, an individual person may have elements of several types and be considered under different types. In a categorization scheme, classes are created for the purpose of placing people into one group or another. There may be occasional ambiguities, but for the most part the placement into groups is clear-cut. In an ideal-typical scheme, on the other hand, ambiguity is the order of the day.

The distinction between ideal types and categories may be made clearer by comparing the Worker to a conventional social-service agency. The Worker's ideal-typical scheme of "Worker and guest" corresponds to an agency's categorization of "social worker and client." However, there is an enormous difference in how these schemes operate in everyday tie. At the social agency, the social workers are paid employees. The records of the agency verify who is a paid employee.

The agency maintains listings of clients. There is, then, a written source by which one can determine whether a given person is social worker or client. Moreover, the social workers are distinguished from the clients by numerous social cues. Social workers have offices, or at least desks. They are better dressed than clients. They have an air of authority. Even an inexperienced outside observer can distinguish the social workers from the clients after a few minutes at a welfare office. At a halfway house, it might take a bit longer, but the distinctions would still be clear.

At St. Joseph's none of this applied. Workers were paid $10 per week "ice cream money" —but so were a number of guests. Workers wore clothes from the same clothing room that supplies the guests, usually had a very unassuming air about them, and, except for the "business manager," had no desk. An observer can be at a house for days and still not be absolutely sure who is Worker and who is guest.

There were a number of persons who had attributes of both ideal types and who most persons in the house were reluctant to classify as one or the other.

Workers at St. Joseph's employed three schemes by which they typified persons with whom they came into contact. The first scheme concerned persons' relationship to the house; the second typified persons in moral terms; and the third distinguished types of deviants.

The first scheme created types of persons according to whether or not they were living in the house and the history of their relationship to the house. Under this scheme, there were several ideal types of persons. I will begin with types who lived in the house.

The first type of person living in the house was the ideologically committed Worker, someone who had come to live at the house out of a belief in the Catholic Worker approach. There were nine such Workers, seven men and two women. All were from the middle class, white, and between twenty and thirty-five years old. Except for the editor of the paper, no one had lived at the house for more than two years, most for less than a year.

The next type was the resident—about a dozen persons who lived in the house, considered it their home, who had come to the house in search of shelter. They were from a variety of ethnic groups (including Asians, Latin Americans, and Africans) and ranged in age from late twenties to late sixties. Many had lived in the house for years, or even decades. It is difficult to think of them as a category because of their range of personalities, abilities, and relationships to the house.

Some residents took no part in the activities of the house. One, in fact, was so seldom even present that it took me over a week to realize that he lived in the house. Others played a major role in putting out the paper. One was in charge of distribution, a position of some authority. Another "took the door" during every soupline, a key position since he had to maintain order in the line and keep out people who seemed to be in a violent mood. Others worked the soup line regularly. Thus, the residents varied greatly in their relationship to the house, so much so that it is only with great reluctance that I group them together. Each contributed to the house in some way, yet some were clearly analogous to "clients" in a halfway house, others contributed as much to the house as they received, and still others were somewhere in between. They were often both receivers and givers of hospitality. A few individual portraits may help the reader to understand them a bit.

Harvey, the man we met on the stairs when I arrived, lived at the house for several years. Before he became a resident he had lived in a flophouse and come in daily to sweep and mop the second floor. At that point he was "less far gone than now."

On a freezing night in February he disappeared. The Workers called hospitals and even the morgue, but did not hear from him for weeks. In March they got a call from a hospital saying, "We have a Harvey Lewis here, and he claims he knows you." They went to visit him and were told that his body temperature had been 80 degrees when the ambulance had brought him into the hospital. Gene, an old-time Worker, said:

I don't know how he survived. He stayed in the hospital a while longer, but he was never right after that— he was like he is now. He used to be weird, but now it was all the time. When he left the hospital he moved into the house. He had no place else to go. That was when we started giving him a shave and shower every week. I've got to do it tomorrow. It used to be Don and I split the duty on that, but since I went away [for a vacation]. Earl has been doing it with Don. Now that I'm back. Harvey wants me to shave him. but I've been too busy. Well, I'll do it tomorrow. A haircut too.

Harvey wandered through the house at will, apparently oblivious to everyone around him. He talked to himself constantly. Once I heard him say to himself, "I'm putting my hand on the doorknob. I'm turning the doorknob. I'm opening the door." It was as though he was trying to convince himself of the reality of his actions. Another time, he announced to the air, "I'm expecting! I'm expecting!"

Although Harvey seemed oblivious to what was going on, he perceived much more than one would expect. He was sensitive to rebukes, often leaving the floor if he was told not to do something. He maintained relations with a few of the old-time residents and Workers, particularly Jones, who always threatened to stuff him in one of the huge canvas bags used for mailing the paper, much to Harvey's delight.

Helen, the woman who answered the door on my arrival, was under five feet tall, slightly stooped as a result of a childhood illness.

She had been living at the house for about two years, but had been associated with it off and on for many years before that. She liked to tell about the time the YWCA had her arrested for vagrancy while she was in Pittsburgh during World War II looking for construction work.

She was at her finest during the soupline, waiting on tables, cleaning up messes, screaming to the dishwasher that we need silverware, admonishing a new volunteer on proper technique, and, especially, breaking up arguments among the guests. All of the guests knew her, usually as "Ma." The volunteers all knew her too. She was the first person to welcome a new volunteer.

But it was in troublesome situations that she really showed her mettle. If two guys in line started arguing and were about to come to blows, the experienced Workers called in Helen. She would come over to the troublesome person and say "Come over here. I want to talk to you." She would ask how he was doing, have him sit down with her, and, after a bit, guide him out the door. Once, I was told, she came up to a huge drunk who was trying to attack someone and challenged him, "You wanna take it outside with me?" He broke out laughing. Even a roaring drunk couldn't take on a little old lady. She could get someone out the door painlessly in cases where the Workers would have to drag the person out.

Harvey and Helen were by no means representative of the residents. If anything stood out about the residents, it was their individuality. There really was no resident "role"—each resident negotiated his or her own role. Harvey's role was akin to that of a resident of a nursing home, although with a bit less systematized care, a lot more freedom, and far more genuine love. Helen created a role in which, for all that she may have been disgruntled with status differentials or the way the house was run, she knew that she was contributing something valuable to the house. Hers was not an artificial dignity created for her by the staff of a nursing home. She had an important role in the overall functioning of the house and she knew it.

Treating the residents as a group does reveal the role of reciprocity in Worker hospitality. Reciprocity is gratefully accepted but not required in return for hospitality. One need not reciprocate to remain a resident.

The next type of person living at the house was the emergency-shelter guest. This was a person who had been accepted for shelter for a limited amount of time—perhaps for a night or perhaps for a couple of weeks. Like the residents, they may or may not reciprocate by helping out around the house, but whether or not they did so had no effect on their length of stay.

Another type of person was the short-term Worker, someone who came to the house to live and work for several weeks or months, generally because of a desire to try out the Worker style of life. This was the type into which I fit. Although there was only one other person of this type at the house during my stay, it was evident that this was a regular type, with which the house had had a lot of experience.

A final type of person living in the house was the visitor. Visitors differed from emergency guests in that they came not in desperate need of shelter, but rather to see the house for a variety of reasons. Generally, they stayed a few days. Visitors included middle-class persons wanting to "see" the Worker for a few days, former New York City Workers, Workers from other houses, and friends or family of Workers. Again, reciprocity was dependent on the visitor. Some helped out for their whole stay; others did little. One visitor was a priest who stayed for a weekend.

Although he attended a Friday night "clarification of thought" meeting, he expressed little interest in the work of the house, not coming to a soupline until his third day. It seemed to me that he was using the house simply as a place to stay until some friends of his returned to town and he could stay with them. No one seemed to mind, though.

A number of important types of persons lived outside of the house. First, there were the Workers and residents of Maryhouse. As at St. Joseph's House, most of the Workers were in their early twenties or thirties and had been there less than two years. There were also several older Workers who had been there much longer. The house had about thirty residents, all women, many older, almost all with mental problems. Maryhouse did not do emergency shelter, so there were rarely any emergency guests; there were, however, a number of visitors, who often helped out at St. Joseph's as well.

Another important type was the Worker living in a nearby apartment. Around a half dozen Workers who had lived at the house for a number of years moved into their own or shared apartments, many of which were owned or paid for by the Worker. Some worked at the house regularly, others stopped by less frequently, but all were still actively involved in the house and would be brought into any important decision making. Most of these Workers were in their thirties and had been involved in the house for a decade or more.

Still another type of person was the "friend of the house." This type of person lived outside the house but, due to a historical relationship to people in the house, had relatively free access to the house much of the time, had a standing invitation to house meals, and frequently helped with the work—particularly the ubiquitous task of folding Catholic Worker newspapers. Friends of the house tended to be older, lower-class white men and women. (Nearly half were women, although there were very few women "on the line"). Many of them had a room or apartment of their own. They had been around the house for years; sometimes, their relationship to the house pre-dated, and was only vaguely understood by, most of the Workers in the house.

Finally, there were the men "on the line," the thousands of homeless New Yorkers who came in for soup, to use the bathroom, to get clothes, or to get bread and butter to go. Many were regular characters, known to all and familiar with the ways of the house. Others were known only by the longer-term Workers. Still others were nameless, coming to the house a few times and then disappearing, or even coming for months without standing out from the crowd in any way.

A special subgroup within the men on the line were the window washers, a group of relatively young black men who lived on the corner of Houston and Bowery, huddling around a fire in their garbage can, who dashed out to wash the windshields of cars stopped at the red light in search of some spare change. Most were alcoholics and drug addicts, but they were a unique group of street men. They were among the few homeless persons who talked in terms of a future and were still able to project themselves as returning to "normal society." They conceived of themselves as entrepreneurs, operating a business whose services were no more imposed upon customers than are the more extensively advertised goods of "legitimate" corporations. They had a special relationship to the house. It was their bathroom, their place to get in out of the cold. Workers came to know them better than most meal guests. As one Worker noted, they respected the house—they knew when they could stay and chat and when they should just use the bathroom and leave. When the police began harassing them that winter, breaking up their fire, destroying their windshield. washing equipment, and telling them to disperse in the middle of the night, the Worker ran an article on their plight.

The second scheme for typifying persons was a moral scheme. Persons, particularly guests, were typed according to certain moral standards. Unlike professional social workers, Catholic Workers felt free to think of people in moral terms, to describe them as violent or greedy or gentle or generous. The two major negative moral typifications (violent and greedy) were related to daily problems at the house—maintaining order and rationing the goods to be distributed.

There were a few guests who, on the basis of repeated incidents, were typed as violent. As one old-time Worker put it:

Some guys are violent. They tend to react to their inner tensions by hitting someone or worse, rather than verbally. We've had some violent guys. One big black guy from Alabama sliced open June [a Worker] above the eye and punched out this guy [another Worker] who was with us. The tension had just been building up for weeks and it exploded... Ninety-five percent of the guys are great. It just takes two or three to start trouble.

One person in particular was regarded as violent. According to one Worker, "Jim is a very sad person who's been with us a long time. We usually don't let him in because he tends to flip out and can start throwing punches." Another described him as "an old friend," who he generally didn't let inside the house.

Those who were typed as violent were more likely to be kept out of the house and given food "to go." At the other end of the moral scale from violent are those who were construed as "vulnerable.” This designation seemed to be applied most often to younger white men and to the elderly.

The second major moral type was greedy or exploitative. One young man was so typed after he had taken a taxi to the house without money, expecting the Workers to pay the $10 fare. The fare was paid by the Worker, but all agreed that the lad was "exploiting the house" and resolved not to do it for him again. A related type was the fraud. Gimbel's Irv stands out in my mind here. Irv stayed at the house for a month to save enough to get his own place. He was well-liked and accepted by all in the house, buying presents for a few of the residents, and even buying some Christmas decorations for the house.

Just before I left for the Christmas holiday, he offered to use his employee discount on a present for my wife. I went with him to the store, picked out something, and gave him the money to get it the day before I left. We arranged to pick it up together on my way to the train station (so it wouldn't get stolen at the house). He never showed up, so I returned to Syracuse sans present. Upon my return after Christmas, I was told that he had disappeared, taking with him $100 in house money from George's room. George was quite upset at the betrayal of trust, particularly since he had befriended Irv and let him sleep in his own room. Others in the house were mystified that Irv would spend four weeks setting up a situation that netted him less than $140. One old-time Worker said simply, "Maybe someday he'll come back and be sorry for what he did."

Those typed as greedy were not excluded from the house, but were watched more carefully than others. The young taxi-user was allowed into the house regularly after that incident just as if it hadn't happened. Irv never came back, but I suspect he would have been welcome for the soupline, at least.

Workers also applied positive moral terms to persons rather frequently. Guests were "all right" or "good guys" if one could trust them. Some were generous; some made one feel welcome.

The final typification scheme utilized conventional deviant labels. Persons coming to the house might be classified roughly as alcoholic, crazy, or drug addicts. The terms were not used in any professional or scientific way, but rather, in a commonsense manner.

There was no attempt to grasp the medical dimensions of alcoholism or to understand the precise differences between schizophrenics and manic depressives. Rather, such general terms as alcoholic and crazy were sufficient to the Worker's needs. These terms were applied as typologies of everyday problems in running the house. Alcoholics were those who snuck bottles into the house or came in drunk and rowdy. Crazy persons were those who "acted out," talked to walls, and so forth. Addicts were persons who presented the Workers with a problem because they shot up in the bathroom.

Although Workers were generally sensitive to the effects of label-ing, they did not rigorously abstain from using standard labels. They sometimes used "very scattered" or "strange" instead of crazy or mentally ill; however, most were not rigorous about language. One Worker told me of a time when he was arguing with a helper who had a history of mental problems. The helper screamed at him, "You're crazy!" to which the Worker replied "I'm crazy? You're the one who's crazy!" In general, Workers would argue that the way one interacts with a person, and the fact that one is willing to live with that person, is more important than the terms one uses.

The overall approach to typification is related to the personalist philosophy of the Worker. The ideal is to grasp the other in his or her fullness. As Schutz has shown, however, one cannot operate without making typifications of others, typifications that hinder one's ability to grasp the other fully. The Worker approach, implicitly recognizing this, attempts to maximize interpersonal relations in three ways.

First, none of the schemes use jargon. Terms used come from the common English vocabulary and are applied for the most part without specialized meaning for the setting. Moreover, the terms are not based on any special theory. Second, the typifications are ideal types rather than categories. There is no need to classify everyone into one type or another. Ambiguity is tolerated, even welcomed. Third, the emphasis among Workers is on personal history rather than type.

Workers are expected to "know the guys." One need not know any theories of drug addiction. One should know that when Abe asks to use the bathroom, he is probably going to try to shoot up there. One need not know the difference between paranoia and schizophrenia. One should know that it is no problem if Harvey chooses to talk to the doorknob.

The Worker approach to typification, then, is designed to maximize appreciation of the guest as a whole person. As such it contrasts with both the bureaucratic and professional models, which use jargonistic categorization schemes to describe persons, an approach that Workers would argue restricts one's ability to grasp the other as a person.

Harry Murray is a professor emeritus of sociology at Nazareth University in Rochester, New York. He spent two years at Unity Kitchen in Syracuse in the late 1970s. He ran the Saturday meal and St. Joseph House in Rochester for over thirty years and was incarcerated in the Salvation Army with Peter DeMott for three months for protesting the Gulf War.

Coming up next week: In the final section of his chapter, Harry Murray covers how the Catholic Workers navigated status and demands on their time and resources.

Read the previous sections in Murray’s chapter here: