Can AI Help Change Attitudes Toward the Unhoused?

Margaret Pfeil, co-founder of the South Bend CW, is working with AI researchers to find out. Also: Dorothy on voluntary poverty; Elizabeth CW hopes for a house; community newsletters, and more.

‘Just This Once…’

On Friday, at Mass (for Catholics), the Gospel story from Matthew told the story of Jesus healing two blind men. “See that no one knows about this,” Jesus commands them. “But they went out and spread word of him through all that land,” Matthew tells us (Matthew 9:31).

I had to laugh. I can just imagine Jesus, a Catholic Worker “on the house,” answering the door, or running the community meal, offering hospitality to anyone who knocked. And, inevitably, personalism means that you make an exception “just this once.”

Sure, clothing distribution day is Wednesday, but it’s January, and you need boots now. I’ll go get them for you, but don’t tell anyone. Ten minutes later, of course, there’s inevitably another request from an observant guest who noticed so-and-so’s new kicks. “Hey, can you get me a pair of boots…”

So it goes, the dance between boundaries (for the sake of the community’s health and your own sanity) and between love that meets a person whose needs do not fit into any rules or system: who needs are facts, unchanging, and you will either respond or not respond to the facts at hand. Jesus doesn’t say to the blind men: “Hey, come back on Tuesday, that’s sight-curing day.” Have pity on us, they cry. It’s a simple request. And he responds.

No good deed goes unpunished, as they say. I take comfort in the idea that even Christ knows what it means to have your hospitality metastasize beyond the encounter in which you offered it.

Today is the feast of the Immaculate Conception (although it’s observed tomorrow in the United States). It’s a day that celebrates Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker on many levels.

Three years ago, Dorothy Day’s local cause for canonization wrapped up with a Mass at St. Patrick’s. I wrote about the Mass for Religion News Service. It was an exciting hinge point in the story of Dorothy’s afterlife in the church.

It was a fitting moment, because Dorothy had prayed at the National Shrine at the Immaculate Conception (under construction at the time) on the feast of the Immaculate Conception in 1932, offering a fervent prayer for her vocation—a prayer for her to find her way forward. That moment of prayer, she said in House of Hospitality (1939), opened her heart to her life-transforming encounter with Peter Maurin a few days later.

“If I had not said those prayers down in Washington, I probably would have listened, but continued to write rather than act,” she said.

Today is a day that reminds me—comforts me—that the work Dorothy set out on wasn’t just her own idea or initiative, but, she believed, was Christ’s work. “What we do is very little,” she wrote in 1940, “But it is like the little boy with a few loaves and fishes. Christ took that little and increased it. He will do the rest.” He’ll fill in the gaps—like when I just told someone to come back on Monday for a shower, or when the number of showers we’ve offered has increased our water bill by a factor of four—the work isn’t so much our idea, but Christ’s.

It’s that belief, that Christ can take the little we do that allows us to open our hearts, to offer someone what they need, just this once, and we trust that love—which seems like so little, just a fish and a loaf—will expand beyond even that small encounter in which we offer it.

peace,

Renée

Correction(s)

Karl Meyer wrote us recently to point out a number of errors in the piece we ran about his talk at the National Catholic Worker Gathering (Karl Meyer: 67 Years of CW Activism in Ten Minutes…Or a Little More). We’ve corrected the errors, but you can read the full stand-alone correction in the post we sent out Saturday. Our apologies to Karl and to you, our readers, for the errors.

THE ROUNDUP

Features

Laughter in the Catholic Worker. Is it gauche to laugh in such grim times...or is it a strategic move that opens up new possibilities? Claire Lewandowski went looking for levity at the L.A.C.W., and shares what she found. Her essay is a wealth of funny stories and wise insights. “It feels true that the Catholic Worker attracts a certain self-serious type: philosophers, dreamers, doers, who have steeped their minds in the evils of the world and come to the Worker for a chance to try their hand at putting things right,” she writes. “But I have also met another type: the joker, the holy fool, the teasing party host who leaves everyone laughing. In fact, these two types often reside in the same person. It’s just that the first one tends to smother the second with a pillow so he doesn’t ruin the moment or distract from the work. I say we let him breathe.” Read her entire essay, first published in The Catholic Agitator, in Thursday’s CW Reads.

What the Myth of the Coffee Cup Mass Gets Wrong—and Why It Matters. People love to tell the story of Dorothy Day’s “Coffee Cup Mass,” in which she is supposed to have personally reverenced a coffee cup that had been used as a chalice during a Mass at the Catholic Worker. But how much of that story is true? As the story evolves with each retelling, it risks overshadowing the deeper truths of Dorothy’s spirituality, Brian Terrell writes. In today’s essay, he explains what this enduring myth gets wrong—and why the reality of Dorothy’s faith offers a more profound lesson than any legend. Read his essay in Friday’s CW Reads post.

What Dorothy Day Learned from St. Thérèse of Lisieux. “Dorothy Day changed my life!” Rosalie Riegle writes in her latest book review. “In fact, she’s still changing it, many years later. Dorothy Day: Spiritual Writings (edited by Robert Ellsberg, published by Orbis Press) changed it still further. Ellsberg has arranged some of her many writings by subject, beginning with ‘The Word Made Flesh’ and continuing through eleven sections, ending with ‘Revolution of the Heart.’ All of her writings are good, and the sections of her diary where she laments her sins were especially interesting. But this time, I was struck by her frequent references to the book she wrote about St. Thérèse of Lisieux.” Find out what Rosalie realized about the deep connection between Dorothy and her spiritual hero in Friday’s CW Reads post.

“How do I get this CW Reads thing?” Glad you asked. If you’d like longer essays and articles in your inbox on Thursday mornings, go to your Substack “Manage Subscriptions” page and toggle the CW Reads button. It’s that simple!

CW Community News & Newsletters

Elizabeth CW Advocates for Basic Rights of Afghan Women. The Elizabeth (New Jersey) Catholic Worker joined a protest at the Afghan Consulate in New York City on Nov. 6, standing in solidarity with Afghan women facing severe restrictions on basic freedoms. The community is also raising funds to establish Magdalen House, a hospitality house for women in need. Donations may be sent via Cashapp ($ElizNJCW), Paypal (@elizabethnjcw), or mailed to PO Box 2203, Elizabeth, NJ 07207. Contact the Elizabeth Catholic Worker for more information.

Norfolk Catholic Worker Urges Action on Nuclear Disarmament. The Norfolk Catholic Worker invites individuals and groups to sign letters urging President Biden to sign the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) before leaving office. The letters also request a meeting with the U.S. Ambassador to the UN to discuss compliance with nuclear disarmament obligations. Supporters are also encouraged to join the Atlantic Life Community in New York City during the TPNW Third Meeting of States Parties March 3-7, 2025, to advocate for U.S. disarmament leadership. Contact the Norfolk Catholic Worker for details.

Nazareth House Celebrates Eight Years. Nazareth House Catholic Worker (Philippines) marks its eight-year anniversary this month with a reflection in its Magnificat newsletter about its core mission as a house of hospitality for LGBTQ+ people and people living with HIV/AIDS. “We want LGBTQ people to be close to God and we don’t — and no one should — put any obstacles on their journey to God. As one of my queer Catholic heroes, Carl Siciliano (a former Catholic Worker himself), said, ‘The Catholic Worker is a radical witness to the primacy of love in the gospels. We are not bishops. We are not tasked with guarding orthodoxy. Our task is to witness to love, to embody love, to be love, and to show the revolutionary force of love in our world.’” Read the entire newsletter, including a report from the 2024 Regional Interfaith Conference on HIV/AIDS.

Casa Maria CW Expresses Support for Marquette Faculty Union Recognition. Marquette University has invoked its First Amendment religious freedom rights to avoid negotiating with full-time, non-tenure track faculty in its College of Arts and Sciences, 65% of whom signed union authorization cards. That’s according to a statement from Lincoln Rice in Casa Cry, the email newsletter of the Casa Maria Catholic Worker in Milwaukee. This is a departure from the practice of other Jesuit institutions like Saint Louis University and Georgetown, which honor workers’ rights to unionize. “Marquette University may still follow the examples of these other Catholic, Jesuit universities and stipulate a free and fair election administered by the National Labor Relations Board or another third party,” Rice wrote, noting that the U.S. Catholic bishops have said that “all church institutions must also fully recognize the rights of employees to organize and bargain collectively with the institution. Learn more at the union website.

Mustard Seed Farm 2025 Internships Open. Mustard Seed Community Farm, a Catholic Worker near Ames, Iowa, is seeking summer interns: “We are actively seeking interns and community members to live and farm with us for the 2025 season. Internships can take place between May and October for 8 weeks or more, and room and board is provided. Please contact us by March 15, 2025, at mustardseedbee@gmail.com if interested.” View the community’s profile at CatholicWorker.org.

Catholic Radical Highlights Social Sin, Nuclear Spending, and Living Out Mercy. Paul Popinchalk’s critique of the U.S. nuclear arms buildup leads the latest issue of The Catholic Radical, newsletter of Sts. Francis and Thérèse Catholic Worker (Worcester, Massachusetts). He recommends The New York Times series “At the Brink,” which documents the growing nuclear threat, and draws on recent Church teaching to argue that people should “take to the streets and educate our fellow citizens” in order to address the threat. In other articles, Scott Schaeffer-Duffy reflects on the concept of social sin, urging Catholics to address systemic injustices like racism, militarism, and environmental destruction. Mary O’Connell shares a personal essay on becoming “more fully human” through peace activism and compassionate living. The issue also features a review of the graphic novel Dorothy Day: Radical Devotion and an essay by Claire Schaeffer-Duffy about her interactions with a very persistent guest. Access the newsletter here.

CW in the News

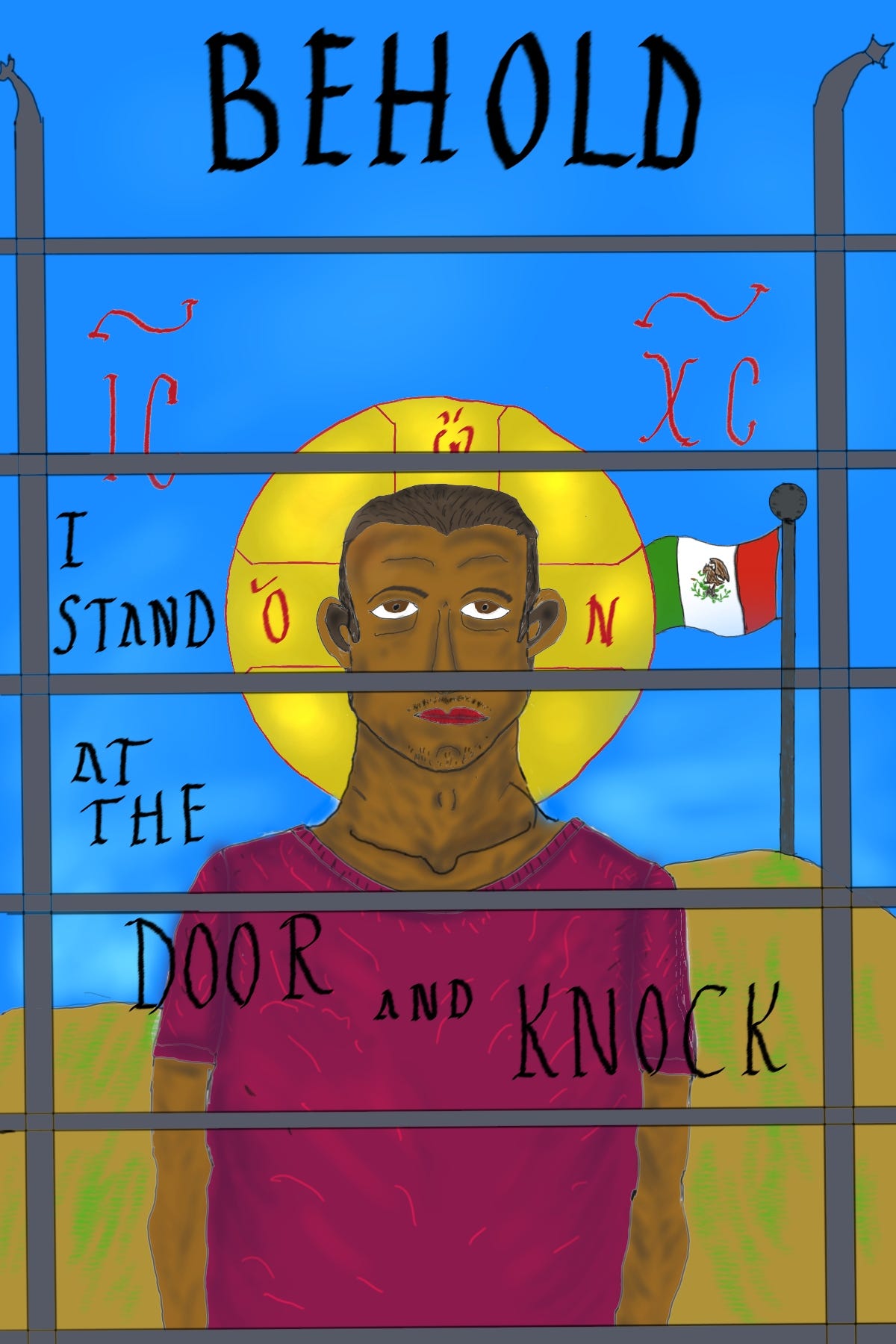

St. Louis Catholic Worker Featured in The St. Louis Review. The St. Louis Review, the weekly newspaper of the Archdiocese of St. Louis, profiled the work of the St. Louis Catholic Worker house in a recent issue. The article highlights how Theo Kayser, Lindsey Myers, and Chrissy Kirchhoefer embody the Catholic Worker ethos through initiatives like preparing burritos for unhoused individuals and providing hospitality to asylum seekers.” Lindsey told the magazine. “By opening ourselves to those who suffer, we open ourselves to God — the God who died among thieves and fed the hungry and overturned the tables of money changers. It’s a beautiful mystery that to love God is to love our neighbor. The face of God is in each of us, and it’s a gift to uncover it.” The lengthy piece includes many photos and a timeline of the various Catholic Worker communities in St. Louis. Read the full article here.

Can AI Change Attitudes Toward Homelessness? Notre Dame theology professor Margaret Pfeil, co-founder of the Peter Claver Catholic Worker community in South Bend, Indiana, is collaborating with AI researchers Georgina Curto Rex and Matthew Hauenstein to address local biases against homelessness. Two initiatives of the South Bend Catholic Worker, Motels4Now and Our Lady of the Road, have faced opposition from county leaders as well as residents. The Notre Dame researchers recently secured a $200,000 grant to develop an AI model that measures and addresses local attitudes toward the homeless, aiming to reshape public opinion and foster community solutions. Read the full story on the University of Notre Dame’s website.

Amistad CW Guests Face Winter Challenges. As winter sets in, 14 unhoused individuals are trying to stay warm by doubling up in six unheated tiny shelters in the backyard of the Amistad Catholic Worker House in New Haven, the New Haven Independent reports. Residents rely on blankets, sleeping bags, and extension cords powering small heaters to stay warm. Read the full article by Jabez Choi in the New Haven Independent here.

The Essence of Catholic Worker Peacemaking. Sarah Scull writes about her recent visit to Strangers and Guests Catholic Worker farm, where conversation turned to peace making and Brian Terrell’s upcoming prison sentence in Germany for entering Büchel Air Base, in a protest of the 20 U.S. nuclear bombs stored there. “This is the essence of the Catholic Worker approach: confronting the systems of violence directly, not with anger, but with clarity and a deep sense of moral responsibility,” Scull writes. Read the full essay on Piecemaker.

Civil Disobedience in Cold War New Hampshire: A 1961 Protest. A recent article by Arnie Alpert in IndepthNH.org recalls a 1961 protest in Durham, NH, in which 18 individuals were arrested for refusing to take shelter during a civil defense drill. The protesters were inspired by similar protests started by the Catholic Worker. Despite condemnation from Governor Wesley Powell and academic probation for participants, the protest highlighted the moral imperative of resisting nuclear escalation. Read the full story at InDepthNH.org.

What Catholic Worker Communities Could Learn From Cooperatives. In the latest edition of Love in Community, Abby Rampone critiques the Catholic Worker movement for its lack of egalitarian governance structures compared to the cooperative housing model championed by the NASCO Institute. Rampone, who attended the NASCO Institute’s 2024 conference, highlights the cooperative movement’s emphasis on shared governance, conflict management, and intentional power structures, which she argues religious communities often lack. “Too often, I’ve seen communities (and myself!) retreat and crumble in the face of conflict,” she writes, urging religious groups to adopt cooperative tools to build healthier, more sustainable movements. Read the full article in Love in Community.

WORDS FROM THE ELDERS

Reflections During Advent: The Meaning of Poverty

by Dorothy Day in Ave Maria magazine, 1966

THERE IS A STORY of Tolstoi’s called “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” It is the story, as I remember it, of a peasant who left his good land and home to go to the South, where he had heard there were thousands of fertile acres for the asking. He made his way to the nomad tribe and asked for some of their land. The chieftain told him he could claim as his own the amount of land he could encompass on foot, from sunup to sundown. When he had rested from his journey he set out running at a pace he felt he could sustain, for he had great confidence in his own strength and endurance, and began to stake out his land. But his greed was greater than his endurance, so his strength began giving out towards the close of the day. By the time he had run the immense boundaries he had chosen for himself, he fell dead at the feet of the Cossack chieftain. He ended in a six-foot grave dug merrily by his scornful hosts, who sensed that the earth was the Lord’s and the fullness thereof.

We had a man living with us once who claimed that all illness was a punishment for some fault. When Sunday visitors came in happily with bunches of poison ivy, picked because of their bright colors or pretty berries, he labeled the visitors as “acquisitive.” It was the fault he most despised, perhaps because it was the one he was most guilty of himself. He wanted to be poor, yet he looked upon all things around him as his own and gathered them to himself.

At the same time, he did not like to work, to be exploited, he called it, in our present acquisitive, competitive society, so he preferred to gather furniture and even slightly spoiled food from off the city dump near the farm, and felt he was exemplifying voluntary poverty.

Another family moving in with us, on one of our Catholic Worker farms, felt that the beautifying which had made the farmhouse and its surroundings a charming spot was not consistent with a profession of poverty. They broke up the rustic benches and fence, built by one of the men from the Bowery who had stayed with us, and used them for firewood. The garden surrounding the statue of the Blessed Virgin, where we used to say the rosary, was trampled down and made into a woodyard filled with chips and scraps left from the axe which chopped the family wood. It was the same with the house: the curtains were taken down, the floor remained bare, there were no pictures–the place became a scene of stark poverty, and a visiting bishop was appalled at the “poverty.” It had looked quite comfortable before, and one did not think of the crowded bedrooms or the outhouse down the hill, or the outdoor cistern and well where water had to be pumped and put on the wood stove in the kitchen to heat. Not all these hardships were evident.

On another farm we owned — a larger place where we could accommodate more children in summer, more families, more men from off the road–there was the same lack of plumbing arrangements and the same need to heat the place with wood fires Even the nearby city helped us out by bringing logs from trees which had fallen in storms and blocked the highways, to increase our store of fuel. The place was old and beautiful, and had a carefully tended flower garden with peonies, iris, forsythia, perennials and annuals that delighted the eye and kept our chapel furnished with color and fragrance. Here one of our prosperous visitors looked around with a censorious eye and commented, “You call this voluntary poverty? I could not afford a country home like this.”

She did not see the three sets of outhouses set back in the trees and bushes which had to be used winter and summer (the temperature often dropped to 10 below zero); nor did she see our bare dormitories with their double-decker beds crowded together, nor the living quarters of a family over the carriage shed that was heated only by an old stove in the middle of the barnlike structure, nor the wayfarers’ dormitory down below where men came in from off the road at any hour of the night or day (and sometimes with a bottle to keep themselves warm!). No doors were ever locked in that farm by the road.

It is not right to justify oneself, but we tried to point out how ungrateful we would be to God and to our benefactors if we did not, by hard work and care, improve what we had received in the way of land and house. The very men who had come to get help had stayed to give help and had made the place what it was by constant hard labor.

But the poor, it seems, have no right to beauty, to order. Poverty must be squalor, filth, ugliness, to be esteemed as poverty. But this is destitution, and it was usually from such destitution that our family had come “up in the world.” Our visitors did not recognize true poverty — voluntary poverty now-offered up by these men for the sake of their fellows . . . a poverty on the part of students and volunteers as well as men from the Bowery, which meant no money to jingle in the pocket, no wages, having to ask for tobacco, to wear the clothes which “came in” and to have no privacy, which is the greatest desire, the greatest need of all.

Right now on our farm at Tivoli, New York, there are five hermits in the woods who have rebuilt old campsites so that, winter and summer, they can live alone.

During the 33 years that the Catholic Worker has been published and the Houses of Hospitality and farms have grown up around the United States, there has always been this misunderstanding of poverty.

For a long while, poverty was denied–we just did not have any, according to popular belief, in our affluent society. Many a time I was queried by students, “Where is poverty? We do not have any around this prosperous Middle West, for instance.” I was asked this question at Notre Dame, when I spoke there, and to show that there was poverty Julian Pleasants and Norrie Merdzinski, both Notre Dame students, started a House of Hospitality in the off-bounds section of South Bend. With the help of Fr. Putz and Fr. Mathis they kept it going during their student years, to care for unemployed and unemployable men off the road. The same question was asked me in Green Bay, Wisconsin, and I could only point out that where there was a Good Shepherd home for delinquent girls, and an Indian reservation, and a prison and a public ward in the hospital, there was poverty. You could always find poverty at the public dump, or in the prison or hospital. All founders of religious orders and societies searched out poverty.

IT WAS Michael Harrington’s book The Other America, and Dwight McDonald’s long review and analysis of that book in the New Yorker, that made the problem explode in this country, to use an expression of Abbe Pierre, who himself works with the destitute and homeless. This book of Mike’s, which came as a result of his two-year stay with us as one of the editors of the Catholic Worker, started the War on Poverty program.

But it is not to discuss solutions proffered by government or city agencies that I wish to write, though this long introduction was necessary to clarify the subject. War, and the poverty of peoples which leads to war, are the great problems of the day and the fundamental solution is the personal response which each of us makes to the message of Jesus Christ. It is the solution which works from the bottom up rather than from the top down, and makes for readiness to join in larger regional solutions like the organizing of farm workers with Cesar Chavez, community solutions of Saul Alinsky, village solutions like Vinoba Bhave’s in India, etc.

The wonderful thing is that each one of us can do something about the problem, each one of us can give his response and can go as far as the grace of God leads him; and God “ordereth all things sweetly,” and there is no need to be afraid as to where such a response will lead US.

“Ask and you shall receive,” Jesus told us, and this asking may be just that question “What shall we do?” Samuel asked it, St. Paul asked it — “Lord, what will you have me do?” and they seemed to get direct answers. Paul was struck blind, literally and to everything else around him except that one great fact, “whatever ye do to the least of these My brethren, ye do to Me.” If you feed them, clothe them, shelter them, visit them in prison (or go to prison and so are with them!), serve the sick, in general perform the works of mercy, you are serving Christ and alleviating poverty by direct action. If you are persecuting them, killing them, throwing them in prison, you are doing it to Christ. He said so.

When the crowd was moved by John the Baptist and asked, “What shall we do?” he said to them, “He who has two coats give to him who has none.” He also said, “Do injury to no man. Be content with your pay.” Or with no pay at all. If you are voluntarily giving away what you have, giving your coat, don’t expect thanks or the reform of the recipient. We don’t do it for that motive, with the expectation of reward. We must do it for love of Jesus, in His humanity, for love of our brother, for love of our enemy.

Charles Peguy in one of his poems, God Speaks, tells the story of the prodigal son and comments, “That’s the kind of a Father we have, who loves even to folly, who forgives seventy times seven, who rushes out to embrace and feast the prodigal son.” This is the kind of love we must have for the poor. The kind of love which will give away cloak also if coat is demanded of you.

Nobody is too poor to help another. The stories in the New Testament are of the widow’s mite, of the little boy’s loaves and fishes, of the cloak, of the time given when one is asked to walk a second mile.

Another Russian story which profoundly moved me was The Honest Thief, by Dostoievsky of the hardworking tailor who lived in a corner of a room, and yet who took in one of the destitute he encountered. The guest begged and drank and the tailor suspected him of stealing his one treasure, an old army coat. He spoke to him harshly, but when the thief ran away, the tailor searched him out and brought him back to his corner to nurse him in his illness. “Love is the measure by which we shall be judged.” And by not judging we too shall not be judged.

I am thinking of how many leave the Church because of the scandal of the wealth of the Church, the luxury of the Church which began in the very earliest day, even perhaps when the Apostles debated on which should be highest in the kingdom and when the poor began quarreling as to who were receiving the most from the common table, the Greek Jews or the Jerusalem Jews. St. Paul commented on the lack of esteem for the poor, and the kowtowing to the rich, and St. John in the Apocalypse spoke of the scandal of the churches “where charity had grown cold.”

It has always been this way in the Church. On the one hand the struggle for detachment, to grow in the supernatural life which seems so unnatural at times, when the vision is dim.

Thank God for the sacraments, the food of life which we can receive to strengthen us. Thank God for the Word made flesh and for the Word in the Scriptures. Thank God for the Gospel which St. Therese pinned close to her heart, and which the murderer Raskolnikoff listened to from the lips of a prostitute and took with him into the Siberian prison. The Word is our light and our understanding, and it is also our food.

About us. Roundtable covers the Catholic Worker Movement. This week’s Roundtable was produced by Jerry Windley-Daoust and Renée Roden. Art by Monica Welch at DovetailInk. Roundtable is an independent publication not associated with the New York Catholic Worker or The Catholic Worker newspaper. Send inquiries to roundtable@catholicworker.org.

Subscription management. Add CW Reads, our long-read edition, by managing your subscription here. Need to unsubscribe? Use the link at the bottom of this email. Need to cancel your paid subscription? Find out how here. Gift subscriptions can be purchased here.

Paid subscriptions. Paid subscriptions are entirely optional; free subscribers receive all the benefits that paid subscribers receive. Paid subscriptions fund our work and cover operating expenses. If you find Substack’s prompts to upgrade to a paid subscription annoying, email roundtable@catholicworker.org and we will manually upgrade you to a comp subscription.