"This solidarity is more important now than ever"

Further clarification of thought on the cuts to USAID and an essay from Dawn McCarty at Casa Juan Diego in Houston, Texas

Over the past few weeks, stories about the unlawful arrests of lawful immigrants—Mahmoud Kahlil at Columbia, Rumeysa Ozturk at Tufts, the terrifying attempts to detain Ranjani Srinivasan— and the news of innocent American residents swept up in the Trump administration’s unlawful deportations of migrants, has prompted a lot of reflection on Catholic Worker’s emphasis on solidarity with the “least of these” — the marginalized and persecuted.

In our own community here in Harrisburg, we have been working to support many of our Haitian neighbors whose temporary protected status is in jeopardy. When we talk with migrant ministries and immigration lawyers, all of them sound similarly numb when trying to offer advice and encouragement for families trying to set down roots and build a stable, safe life for their children in bleak, uncertain times. The assaults on the rule of law and the flagrant unconcern for human rights have scared many unflappable advocates.

The many conflicting executive orders and judicial rulings foster chaos and instability. In such a politically chaotic environment, as the community at Nazareth House in the Phillippines discussed in a recent newsletter, the marginalized and weak are particularly vulnerable. We share an item from their recent newsletter on how the freezes of funding at USAID created instability for the population they serve.

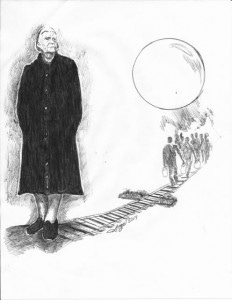

Dawn McCarty’s essay today reflects on the work she does at Casa Juan Diego to support their immigrant guests. Dawn proposes that a spiritual work of mercy we can offer our immigrant neighbors is simply bearing the cross of danger and precariousness that they have carried with them many miles to the U.S.A., and that they continue to carry today.

“While we do many tangible things at Casa Juan Diego to support asylum seekers, refugees, and other migrants, the most powerful thing we do, something that can only happen in this radically different social arrangement, is to take on, willingly and by intention, some of the precariousness of their lives”

I, personally, found her words encouraging, reminding me to hope when it is easy to despair. “God meant things to be much easier than we have made them,” Dorothy Day wrote. A life of peace, free of violence and full of the dignity of creativity “raising what we eat and eating what we raise,” as Peter Maurin envisioned, should not be so hard.

Perhaps one lesson of solidarity is that as we work to build that society in which “it is easier to be good,” we can make sure not one of our neighbors suffers alone. In fact, perhaps abandoning just a little bit of our own comfort and security to enter into the precarity of our neighbor is the blueprint of that better society we seek.

peace,

Renée

Nazareth House on USAID

From Magnificat, published by Nazareth House, Manila, the Philippines.

In late January 2025, we heard some shocking news. First, the newly inaugurated US President, Donald Trump, temporarily halted foreign aid, which included funding for HIV healthcare services.

A few days later, Trump also halted the distribution of US-funded HIV medications in foreign countries. But then he rescinded the order regarding medications a few days later. However, by February 27, the order was again reinstated.

A recent report says that if the US funding is not reauthorized from 2025 until 2029, six million people in the world could die. This year, the Philippines stands to lose $25 million in HIV funding. We were in a panic since our roommates and many friends living with HIV/AIDS in the Philippines rely on free medications from the government. Many HIV programs here in the Philippines rely on some funding from the US.

While the Philippines have laws that mandate the government to provide free HIV medications, the question is, how much does the Philippines rely on its US ally for medications and HIV-care? If the free medication supply dries up, buying HIV medications is cost-prohibitive.

Besides, we don’t know if we could simply buy HIV medications from any pharmacy since, at the moment, they are distributed through government-funded health institutions. We have to think of something to plan this out in case the worse happens. We are currently trying to scout out legal ways to obtain HIV medication in case the worst does occur. This really makes people living with HIV/AIDS vulnerable to the whims of the political order.

With or without Trump, political leaders in the conservative Philippines could technically reduce (or, God forbid, eliminate) funding for HIV/AIDS health care. So it’s all the more important that the Philippines elect leaders who are committed to justice, especially for the poor.

Studies show the lack of equity and justice in terms of healthcare for the poor; that is, the rich can afford healthcare while the poor cannot and are not provided adequate resources due to the government’s mismanaged budgetary priorities.

Nazareth House (Bahay Nazareth) is an ecumenical house of hospitality rooted in the spirit of the Catholic Worker Movement in Manila. Bahay Nazareth provides a home to persons living with HIV or AIDS.

Catholic Worker Principles and the Precarity of Migrants

by Dawn McCarty, PhD, LMSW

I live in two worlds. For the past 16 years, I have been serving immigrant communities at the Houston Catholic Worker, offering the Works of Mercy, both Corporal1 and Spiritual2 to all that cross our door. My day job is directing the social work program at a local university.

This is a juggling act—the changing of clothes from one setting to the next, trying to remember did I take a shower; did I eat, which language am I speaking?

At my university, I am important: senior in rank and status with a fancy title and beautiful office, addressed as “Doctor.” At Casa Juan Diego, I am the opposite: small, no office, not addressed by any title (or even my correct name most of the time), not special, not important, not even paid.

This is by design. The Catholic Worker movement is based on a totally different worldview, one that rejects the climb-the-ladder-of-success ethos of both modern universities and social work organizations. Whether in government, non-governmental organizations, or the private sector, most organizations operate bureaucratically – top down, with workers and bosses, workers filling slots on an organization chart and judged by how much they contribute to goals set by the bosses. The work is seen as more important than the workers. All too often, workers are just cogs in the machine and, if the worker can be replaced by robots, computers and/or computer algorithms, so much the better.3

This model, as applied to organizations tasked with meeting the needs of migrants, was arguably not working all that well in the past, but the institutions themselves are now losing their funding support.

As programs lose resources and capacity seemingly by the hour (Catholic Charities laid off 120 employees in Houston last month—most of them in the refugee resettlement programs), the distinction between my two worlds, the decentralized and socially deconstructed Catholic Worker model and the professionalized welfare world has become only too obvious.

The “shock and awe” attacks on the budgets and staffing of professional agencies, attacks on their very mission, have stunned their leadership. What worked in the past for them was clearly not going to work in the future.

The Catholic Worker movement started during the Great Depression, another time when the old ways were no longer working. By 1933, the economic system had collapsed, and President Hoover’s attempts to deal with the problem were making it worse. Millions of people in dire need of even the basics of food, clothing, and shelter were losing hope. That was the year that Dorothy Day, the co-founder of the movement, opened the first Catholic Worker House of Hospitality.

Nobody thought, then or now, that a Catholic Worker house, or a thousand Catholic Worker houses for that matter, were going to end the Depression. The scale of suffering was just too great.

Dorothy believed, however, that we were called to do all we could, in line with what we believed; results were up to God. The beliefs, the core principles behind her actions, were what counted most.

I believe that once again we are in revolutionary times and that our Catholic Worker principles have much to teach our formalized social welfare system about how to understand and deal with the new world we are facing.

For instance, personalism, which emphasizes our individual responsibility for helping others instead of relying so much on the government and other large institutions. Catholic Workers put personalism in action by living a simple life in community, actively working against violence in all forms, performing the works of mercy in whatever context is present. Instead of operating on government funding or grants, we rely on the donations of our supporters. All the money that is given to us is used in direct service to others. In our space of freedom, where we take no money from any government or institution, we can build the sort of society we want to see. We can model for others how it would look, and the good that it can do.

This model is also healing for everyone, protects the staff and volunteers from burnout, and has the best chance to promote the conditions of empowerment for those at the bottom of our stratified social systems. At Casa Juan Diego, many different people come to collaborate, and the Catholic nature of our movement is easily expressed by all in the ways that we give priority to the dignity and worth of the human person.

While we do many tangible things at Casa Juan Diego to support asylum seekers, refugees, and other migrants, the most powerful thing we do, something that can only happen in this radically different social arrangement, is to take on, willingly and by intention, some of the precariousness of their lives. This solidarity with the poor is why no one here is paid a salary, why full-time staff share housing and meals with our guests, live in the same conditions and eat the same food, showing them that they are valued and loved. This solidarity is more important now than ever.

And most importantly, in this space of freedom, we can welcome the stranger. This is a power that cannot be taken away, despite the xenophobia of our time. I am reminded in every conversation, and in every act of care at Casa Juan Diego, that this is my country too, and I get to decide how I respond to others. I get to welcome those that the Gospel wants me to love. This ability does not come from the government, but from a much higher power.

In our Catholic Worker community, our band of sisters and brothers are as strong and as confident as ever in our commitment to the poor and to the works of mercy. In the Catholic Worker model, we get to dream and build the society that we want to see here on earth, a society based on the good of all.

Dawn McCarty is a founding faculty member and Director of the University of Houston-Downtown Bachelor of Social Work Program and a part-time community member at Casa Juan Diego. This essay first appeared on Casa Juan Diego’s website.

Corporal Works of Mercy: Feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, clothe the naked, shelter the homeless, visit the sick and imprisoned, and bury the dead.

Spiritual Works of Mercy: Instruct the ignorant, counsel the doubtful, admonish the sinner, comfort the afflicted, forgive offenses willingly, bear wrongs patiently, and pray for the living and the dead.

St. John Paul II’s very first Encyclical as Pope, Laborem Exercens, was released in 1981, one year after Casa Juan Diego was founded. It called for a human-centered approach to economic systems.The worker is more important than their work! This and others of his Encyclicals are well worth reading. http://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en.html Click on Encyclicals.

About us. Roundtable is a publication of catholicworker.org that covers the Catholic Worker Movement.

Roundtable is independent of the New York Catholic Worker or The Catholic Worker newspaper. This week’s Roundtable was produced by Renée Roden and Jerry Windley-Daoust. Send inquiries to roundtable@catholicworker.org.

Subscription management. Add CW Reads, our long-read edition, by managing your subscription here. Need to unsubscribe? Use the link at the bottom of this email. Need to cancel your paid subscription? Find out how here. Gift subscriptions can be purchased here.

Paid subscriptions. Paid subscriptions are entirely optional; free subscribers receive all the benefits that paid subscribers receive. Paid subscriptions fund our work and cover operating expenses. If you would like to stop seeing Substack’s prompt to upgrade to a paid subscription, please email roundtable@catholicworker.org.

"Perhaps one lesson of solidarity is that as we work to build that society in which “it is easier to be good,” we can make sure not one of our neighbors suffers alone. In fact, perhaps abandoning just a little bit of our own comfort and security to enter into the precarity of our neighbor is the blueprint of that better society we seek."

Catholic Education in Solidarity with the Poor

Recent popes have declared that the “rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer”. This same criticism could be applied to Catholic education: Catholic schools and colleges are serving more the rich; and less the middle class and poor.

When my grandparents emigrated from Ireland in the early 1900s, the Catholic church in the United States already had in place a parochial school system designed primarily for immigrants. However, these schools are now too expensive for today’s immigrants.

St. Ignatius of Loyola, when he established Jesuit schools and colleges in the sixteenth century, insisted that no tuition fees be charged to the students in order that the poor might participate with the rich. Today, student fees in some of our Catholic colleges are exceeding $60,000 a year.

Should Catholic education include, as part of its mission, the goal of reducing the gap between the rich and poor?

Practically speaking, the Catholic schools must give up general education in those countries where the State is providing it. The resources of the Church could then be focused on Confraternity of Christian Doctrine and other programs which can be kept open to the poor. These resources could then be used to help society become more human in solidarity with the poor. Remember, the Church managed without Catholic schools for centuries. It can get along without them today. The essential factor from the Christian point of view is to cultivate enough Faith to act in the Gospel Tradition, namely, THE POOR GET PRIORITY. The rich and middle-class are welcome too. BUT THE POOR COME FIRST.