"This place is too near the Ritz": On Status at the Catholic Worker

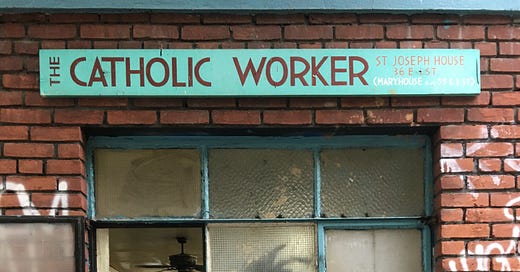

Our final selection from "Do Not Neglect Hospitality": Harry Murray on the challenges of equality in community at St. Joseph's House of Hospitality in New York City.

We continue our serialization of a chapter from Harry Murray’s “Do Not Neglect Hospitality” with his final observations about St. Joseph’s House in New York City. He tackles the difficult question of status and class at the Catholic Worker.

You can read part one of Murray’s chapter on St. Joseph’s House in New York City here, part two here, and part three here.

Harry Murray’s chapter hit home for me, as I’ve been thinking recently about the paradox of hospitality, the tensions that pull you to draw healthy boundaries and push you to ignore rules to show generosity. As St. Vincent de Paul once said: “It is for love alone the poor forgive you the bread you give to them.”

Without these tensions, Catholic Worker houses—as Pope Francis said of the Catholic Church—become places of “spiritual worldliness,” closed-in, self-referential, and with hardened hearts. Such spiritual worldliness is a temptation for us all—every human heart can choose to harden itself to the cry of the poor or heed it.

One guest gave Harry Murray the following critique:

I thought if one were to follow Christ one must empty himself, forget matters of status. But here, you still make judgments—judgments about status, about propriety, in answering the door. Here the com-panionship, the service, is for the people inside. The Crispy Rice is for the people inside, for the guys who work at Gimbels. I have a great sin on my soul just being inside this door, but I'm too weary to care. This place is too near the Ritz, too near the downtown businessman who doesn't want his life interrupted by those on the outside so he puts a doorman at the door to keep them out. It's lukewarm.

His words reminded me of Patrick McKenzie’s recent article in Radix (which will be appearing in full in Roundtable next week) on seeing the Lazaruses sitting on his doorstep. The rich man is not condemned, McKenzie noted, for causing Lazarus’ misery or creating the socio-economic conditions that led to his indigence. No, rather, the rich man (Dives) is judged based on his indifference toward the hungry man at the door.

This saying is hard! Who can accept it? Harry Murray writes realism, not hagiography. Which means his perceptive analysis of the delicate issues of status in a Catholic Worker community provides a valuable look into the mirror of our own hearts. What divisions are we willing to passively accept or endorse?

peace,

Renée

Catholic Worker Hospitality

From the Chapter, “The Flagship,” in “Do Not Neglect Hospitality” by Harry Murray

Problems of Status

St. Joseph's is an amazing experiment in egalitarianism, attempting to bridge one of the widest social gaps in America—that between the middle class and the homeless. To observe that there are still status distinctions within the house is by no means to judge the experiment a failure. The traditional class divisions of American society are diminished to a remarkable extent by sheer willful effort, although they are still discernible in subtle, often disturbing ways.

One of the ways the house seems to have attenuated class distinctions is by creating a second status distinction that conflicts with, and thus undermines the first. The distinction that reflects social class is between those who come to the House out of ideological conviction and those who come out of need. The distinction that undermines social class is between those who are "in the House" and those who are "on the line."

The Worker-Guest Distinction

Worker houses vary greatly in the extent to which they try to eliminate distinctions between the largely middle-class Workers and their homeless guests; however, each house makes some effort in this direction. The very act of living together eliminates many distinctions. Residence is an important element of social class even though it is often ignored in sociometric scales. Classes do not generally share neighborhoods (unless "declining" or "gentrifying"), let alone living quarters. Living in the same household as another, even sharing a room, makes it difficult to maintain many of the differences in lifestyle that are essential elements of class distinctions. Furthermore, the middle-class Worker and the resident from the streets perform many of the same tasks every day-washing dishes, mopping floors, folding newspapers, cleaning tables. Thus, two major elements of class distinction—residence and occupation—are largely eliminated by the Catholic Worker approach.

Other class differences do remain, however—most notably education and the fact that a middle-class volunteer has social margin, that is, social acceptance that will facilitate reentry into "normal society" (Wiseman 1979). Workers are aware that this distinction is never eliminated. A Worker at another house put it well:

There is one tension at this place that is probably more important than any other. It's between the plight of the staff and the plight of our guests. It's irreconcilable.

We've chosen to be here, and that's a luxury of the class, culture, economic system (or whatever it is) into which we were born. At any moment, we know, we could leave West Fifth Street for a clean, air-conditioned place where we would be welcomed and loved. They can't (Garvey 1978, 96).

Many in the Worker movement, both middle and lower class, state that the ideology versus need distinction is inaccurate—that everyone at a Worker house comes out of need, whether that need be physical. psychological, social, or spiritual. A common theme among Workers runs. "If we fit into regular society, we wouldn't be here.” There is, then, a continual debate within the movement as to whether there should be a distinction along the lines of ideology versus need.Nonetheless, in each house I have visited, this distinction is made to some degree.

Ken stated the problem this way:

There is a sort of second-class citizenship here. It's subtle, but it's there. I mean there's volunteers like me and then there's the residents. Maybe it's somewhat the residents' choice. I mean Norb [one of the residents] isn't interested in helping out in the soupline. But it's not very egalitarian. And after awhile you start to make assumptions that, of course, residents don't do this or that.

A Maryhouse Worker defended the notion of a distinction with respect to practical matters such as alcohol:

Some people feel there should be no distinction between guests and Workers, but I don't see it that way. Like alcohol [which is forbidden in the house). One time [a Worker] had a friend visiting and they were in my room and wanted to have a beer. So I said sure and they went out and got a can of beer each. [Another Worker] heard about it and got all upset. She wouldn't come to me. Finally she told me that she was upset and I said yea, I heard. She told me why and I said "You have every right to think that. I understand your position. But this is my room, so you should let me do what I want to here." So we made our peace. She didn't complain when we had alcohol here at her going-away party.

Thus, a distinction exists between Workers and guests—with respect to participation in decision making and with respect to privileges. But it exists in tension with an ideal of egalitarianism and is thus often muted. Major decisions about the house are often made by the ideologically committed Workers or even by a subgroup of the most experienced Workers. However, there is an effort made to include residents in such decisions, as in the house meeting described previously.

The distinction is further blurred by the fact that there are a number of status indicators that partially blur the distinction. One such status category is "on-the-house Worker." While I was there, only Workers took the house. However, this apparently had not always been the case. Once, while a couple of us were discussing a particularly troublesome and withdrawn guest, one of the Workers commented, "How far he's fallen. Do you know that at one time he took the house?" A second category is the group receiving “ice cream money"—the $10 per week stipend. All Workers receive ice cream money, but so do a number of residents. A third category is the group that has keys to the front door. Again. all Workers are given keys (eventually—it took two weeks in my case), but so are a number of the residents. Thus, all Workers enjoy the status privileges of ice cream money and a key—and so do a number of residents. This fact has two implications. First, it partially mutes the Worker-guest distinction. Second, it suggests that Workers and guests are ideal types rather than categories. Some of the ambiguities involved are reflected in the career of Gene.

Gene was an aging gentleman who came in during lunch on Super Bowl Sunday. He was neatly groomed, wore a suit, tie, and overcoat, and spoke in an educated manner. He returned later that afternoon while we were on the second floor watching the game. He asked me, "Is it safe to leave my clothes out here while I take a shower?" I said,

"I guess so. Did [the person on the house] tell you you could take a shower?" "Yes." He took a shower, something that simply isn't done by persons not living in the house. A few people, myself included, looked quizzical, but no one said anything since it was the responsibility of the person on the house. In any event, breaching the shower gap was his first major step into the house. He said he would leave a shirt here to dry and be back for it in the morning. "It isn't all that difficult walking the streets. And I can go to Penn Station and sleep there. Nobody bothers me."

This, apparently, was Gene's way of surviving on the streets— look and act middle class in order to create enough role confusion so that people didn't perceive him as a street person. Thus, he could stay at Penn Station because he didn't look homeless. Similarly, his demeanor threw us off a bit at St. Joseph's—we didn't know quite how to respond.

A few months later, one of the Workers updated me on Gene's story. He kept coming around the house and eventually was allowed to stay. He soon began acting like he was in charge of the place.

Because of his appearance, the guys on the line accepted him as an authority. The Worker recounted, "If someone came in for clothes and I was on the house, he would tell me, "Why don't you run down and get him some clothes. I'll keep an eye on things up here.' Or he would tell Ken, 'Son, why don't you do this for this poor guy.’”

He began answering the door, which is the most jealously guarded prerogative of the person taking the house, and was told not to. However, "He still would act like he was in charge when the guys came in. We finally asked him to leave. He came back three days later with a broken foot. We didn't want to take him back, but what could we do? And within a few days, even with all that, he was acting like he ran the house again. We had to ask him to leave."

Gene's story illuminates the nature of the distinction between Worker and guest—the line between them is often vague, but it does exist. I find it hard to imagine him being able to act as he did for even an hour at any social-service agency, where the staff-client distinction is firmly fixed, a gap rivaling that between Dives and Lazarus

The In-the-House/On-the-Line Distinction

The most important status distinction at St. Joseph's was one not derived from the class structure of the larger society, but rather one that was particular to the house itself: the distinction between those “in the house” and those "on the line" The distinction did not refer so much to whether one was actually living in the house as to whether one was automatically allowed in the door. If one had to explain why one wanted to come inside, then one was not "in the house." This is illustrated by the time when I answered the door and found a middle-aged man I'd never seen before. When I asked him what he wanted, he replied, "I'm a friend of the house," with just the right tone of indignation to let me know I had no right to question his right to enter. I immediately let him in.

Perhaps the most obvious consequence of the in-the-house/on-the-line distinction had to do with food. The better food was usually reserved for those "in the house." Those off the line were given bean soup, bread and butter, and coffee during the soupline. At other times they were given bread and butter. Occasionally they were allowed tea or coffee depending on the discretion of the person taking the house. A few were allowed in to eat the supper leftovers if there were any. If cold cuts, meat, desserts, fruit, or vegetables were donated, it was expected that these would be saved "for the house" and not be given out to those who come to the door during the day or used for the soupline meal. One volunteer told me that she had gone to some butchers and begged two hams, which she planned to use for the soup on her shift. She left them in the cooler with a note saying they were for the soup. As she finished the story, "When I got in the next day they were gone. The people in the house had eaten them. Now, whenever I want meat for the soup, I bring it in under my arm the day I'm going to put it in."

Those on the line were expected to understand the distinction. And most did. People came in to use the bathroom even during supper and left immediately after receiving some bread and butter, while those "in the house" continued with their meal almost oblivious to the outsiders. During the times between meals, people in the house sat and drank coffee although none was offered to those who came in to use the bathroom. Those who challenged the distinction could be labeled troublemakers. One afternoon a man came in, somewhat drunk, to use the bathroom. When he was done he asked the person on the house, "Can I have a cup of coffee?" She replied, "No. That's for the house." He began cursing her and left. Shaken by his anger, she characterized him as a troublemaker.

There was a similar distinction in terms of space. Those on the line were almost always confined to the first floor. Anyone found on another floor would almost always be challenged.

Other privileges and rights also accompanied the distinction. Packs of Tops tobacco were meant for distribution to residents and friends of the house. It was a rare occasion when a pack went to someone on the line, and woe be to the Worker who was caught in the act of giving it to a homeless person by one of the residents.

The force of the distinction could be influenced by the person taking the house. In general, those who tried most to mute the distinction were the newer Workers and the part-time volunteers. These tended to offer people coffee when they had time, and often tried to give out something better than bread and butter, such as adding some peanut butter to the sandwiches. One Worker responded when I brought up the issue, "Well, I guess one thing you can do about having two classes of people is to try to alleviate the difference. You can invite people in while you're making them a sandwich, and not make them wait outside."

Those who did try to mute the distinction, however, came under heavy fire. The strongest defenders of the distinction were the residents. My field notes are full of situations where I was criticized, or saw another Worker criticized, by a resident for giving someone off the streets a privilege reserved for those in the house. Once, a bag of pastries was donated during my shift and I gave some of them to some street men who had come in to use the bathroom. One of the residents said to me the next morning. "Why did you let those bastards off the line have those sweet rolls last night? We could have had them for breakfast. They were for us, not for those bastards." Another time, when a young black man was sitting drinking coffee at my invitation, a resident came down and said to me, "That guy shouldn't be roaming around here. He's off the line." Still another time, I came down to help cook the supper and found the cook (a resident) in a frenzy because the person on the house had let several people in for coffee. "You've got to get these people out of here! I can't cook with them all in my way."

Perhaps the most amazing example was the day I destroyed my relationship with Brother Francis. Brother Francis was an older man who lived in one of the flophouses nearby and had been coming to the Worker for over fifteen years to take care of the garbage and feed the cats. He conceived of himself as another St. Francis, friend to all animals. When he gathered enough slop from the meals, he would try to convince someone to drive him to a nearby park where he would strew it on the ground as food for the birds. He loved his cats, crooning to them and telling them (just loud enough so everyone could hear) that they were infinitely superior to the humans in the house. Every Worker felt the lash of Brother Francis's tongue. I, however, began on his good side, largely because, on my first time on the house, I did not object to his taking a slice of liver to feed his beloved felines.

My falling out with him came one afternoon when I was on the house. He came in to find the dining room empty except for one little old bag lady I had allowed in for some coffee. Although she was a "friend of the house," she was no friend of Brother Francis. He began screaming at me in his high voice. "She shouldn't be in here. She stays at the women's shelter. She comes in and sits around all afternoon. You shouldn't have let her in!" His vision of perfect hospitality, it seemed, was a house containing only himself and the cats.

Residents were not, however, the only protectors of the distinction. Workers constantly balanced the interests of "the house" with those of the people off the line and usually resolved matters in favor of the house. During one soupline when it was cold and raining outside, Ken and I decided to try a different approach to handling the line.

Rather than make people wait outside until spaces opened up, we told them to come in and wait on the stairs. The situation was crowded, damp, and a bit unruly; however, it was all we could think of at the time. A more experienced Worker commented: "You shouldn't put people on the stairs because they get slippery and someone like Mabel might fall coming down. We usually just make people wait outside on days like this. But we should have had one or two people outside to watch the line to prevent people from crowding and shoving at the door."

At a meeting in which we discussed adding a fourth day to the soupline, one newer Worker suggested having coffee and bread one or two mornings a week as an alternative. A more experienced Worker replied, "That time-seven-thirty to nine—is breakfast time for the house and there really isn't any other space for that. We have to consider the people in the house."

Despite the strength of the distinction, the barrier between those on the line and those in the house was not impenetrable, as illustrated by the story of Donald. Donald was a small, balding man in his forties or fifties who started coming to the house during my stay. He stuttered on occasion, or perhaps it was only that he was constantly shivering. When I asked him where he was staying, he would respond, "I've got a cold-water flat." From the way he shivered it was more than the water that was cold there. When I was on the house I'd always let him stay in longer than normal to get warm. A few times he asked about staying in the house, but was told that he could not, for fear he would become a permanent resident. Eventually, he began coming to house meals regularly.

A few months after I left the house I asked one of the Workers about Donald. She told me that he was still coming around, not only for lunch and supper but also for the soupline. She said that his situation was brought up once at a Sunday night meeting. People were wondering how he had come to be a regular at the meal. Ken said he thought he had let him in first. Another person said she thought he was one of Sue's friends. No one was quite sure how he had achieved the de facto status of friend of the house, but no one wanted to take the responsibility to tell him he couldn't come anymore, so he kept coming. I suspect that many friends of the house achieved their status in a similar way—at least to the extent that no one was quite sure how they became "friends."

By far the harshest critique of the in-out distinction came from one of the guests, an electrical engineer in the defense industry who had quit his job and taken to the streets after a religious conversion experience. I will piece together here a few of the comments he made:

I thought if one were to follow Christ one must empty himself, forget matters of status. But here, you still make judgments—judgments about status, about propriety, in answering the door. Here the com-panionship, the service, is for the people inside. The Crispy Rice is for the people inside, for the guys who work at Gimbels. I have a great sin on my soul just being inside this door, but I'm too weary to care. This place is too near the Ritz, too near the downtown businessman who doesn't want his life interrupted by those on the outside so he puts a doorman at the door to keep them out. It's lukewarm.

This morning I waited until everyone had come in [for the soupline] before I came in. I didn't feel that I could say "I'm special" and cut ahead of the line and just walk in. I don't feel comfortable with the door here—the difference between those in and those out. That's why I loathe being in this place. [It's) a country club inside with a few crumbs going out the door. I see very little of what I'd perceived to be the spirit of Dorothy Day here.

In the course of his critique, he made it clear that I was as guilty as anyone else: "How many times have I heard you tell someone, You have to leave because I have to clean up now, when in your heart you were thinking. 'You have to leave so that you won't be in here when we eat. You say you understand about the door, but then you do the same thing as before. What good is it if you understand but don't change what you do."

How did such a sharp status distinction come into being? What functions did it perform? A few partial answers present themselves. In the first place, the very act of giving shelter to some homeless people creates an important status distinction between those who are given shelter and those who are not. Once this distinction is made, those who have been granted the higher status have an incentive to maintain and reinforce it. The residents of the house see a sharp distinction between "in" and "out" because that is the major status distinction between them and "those bastards on the street." Middle-class Workers need not be as committed to the distinction because there are other status differences between themselves and those on the street—their education, their middle-class upbringing. their social margin. In short, those on the line are not a reference group for the Workers, but they are for the residents.

The situation is intensified in New York City by the sheer number of homeless. St. Joseph's is faced with the immense problem that its meager resources can't possibly deal with the thousands of homeless people in the city but Catholic Worker ideology forbids making restrictions on who is given food. The solution, as will be discussed below, is to reduce service quality in order to reduce demand. There is, however, no need to reduce quality of food and other services to those actually living in the house. Thus, the economics of supply and demand work in this case to sharpen the distinction between those in the house and those off the line.

Methods of Restricting Demand

There were over twenty thousand homeless persons in New York City. The dining room at St. Joseph's House seated twenty-eight. This posed a problem. Catholic Worker ideology demanded that no one be turned away when they come asking for food. This exacerbated the problem.

The realization that there were countless hordes of homeless persons "out there" permeated life at St. Joseph's. It was illustrated every time the soupline got overcrowded, which was fairly often. When the weather was good, the person at the door simply allowed between thirty and thirty-five people inside at a time. The others waited in line outside the door. When it was raining or bitterly cold outside, however, the person at the door often let another ten or fifteen people crowd into the dining room, where they would stand two or three deep by the walls waiting for a chair to open up. Everyone became more tense, more irritable. When so many crowded inside, there was no system to assign chairs on a first-come, first-served basis, so there were innumerable arguments over seats. Guests who were already emotionally high-strung became even more so. This tension level could not be maintained throughout a two-hour soupline without the possibility of serious violence.

The person taking the house was responsible to deal with the situation. The accepted solution was to eliminate the serving of seconds. If anyone wanted seconds on soup or bread, they got back in line. This reduced the time a person spent eating and increased turnover-within fifteen minutes, the crowd usually thinned out.

Thus, the strategy for coping with the immediate problem of excess demand on the soupline was to restrict supply-to restrict the amount each person could eat, rather than the number of persons allowed to eat. However, the house's approach to the larger problem of infinite demand was different. The Workers tried to decrease the demand itself by either decreasing the quality of the service or food or making its distribution so erratic that people couldn't depend on it.

One example of this was the quality of the soup itself. It was almost always a bean, split pea, or lentil soup. Meat, if any, was generally leftover from previous house dinners. The oral history of the soup was interesting —old-time Workers claimed it was far better than it used to be when Dorothy was there; however, old-time residents claimed that the quality of the soup had gone down considerably in the last few years. I have no way of determining which account is correct. It does seem, though, that the quality of the soup was kept low primarily out of fear that if it was better the house would be overwhelmed by hungry homeless persons.

A second example was the food that was handed out at the door. Almost invariably this consisted of bread (often stale) and butter. I once suggested to Ken giving out peanut butter and jelly sandwiches instead of bread and butter. He replied:

That would cost a lot. But maybe cost isn't a problem. I don't know. The argument that would be used against it is that too many people would start coming. There'd be a crowd of people all the time if we gave out peanut butter and jelly. In the summer we gave out tomato and mayonnaise sandwiches, which I guess have more nutrition than bread and butter.

A few days later, I was downstairs and found him giving out tuna fish and cheese sandwiches made from leftovers from the house dinner. He invited several people in while he made up the sandwiches. Six or seven newcomers arrived within a couple minutes after the first left. One of the window washers came in with a big smile, saying "I just got it on the wire that you have tuna fish." The tuna fish was gone within fifteen minutes. Ken turned to me and said, "That's one of the arguments against giving out peanut butter and jelly: this sort of thing would happen. People hear there's something good and they all come."

A third example is the distribution of house money to those who come to the door. Every evening the person taking the house is given an envelope with about $10 in it to distribute as she or he sees fit. (The first evening I was given the money, I was told. "The house money is to be given out on the basis of need and, in a few cases, on the basis of tradition, which bears little relation to need.”) Usually it is given out to people coming to the door asking for "car fare," a dollar or less at a time; however, sometimes one gives away three to five dollars if someone's story sounds somewhat realistic. Many, if not most, of the people asking for money, however, are turned down. One Worker told me, "The only way we avoid being swamped is by being erratic in who we give money to."

Harry Murray is a professor emeritus of sociology at Nazareth University in Rochester, New York. He spent two years at Unity Kitchen in Syracuse in the late 1970s. He ran the Saturday meal and St. Joseph House in Rochester for over thirty years and was incarcerated in the Salvation Army with Peter DeMott for three months for protesting the Gulf War.

Coming up next week: a new interview with Harry Murray.

Read the previous sections in Murray’s chapter here: